9.2 Individual Differences in Intelligence

Learning Objectives

- Explain how very high and very low intelligence is defined and what it means to have them.

- Explain how intelligence testing can be used to justify political or racist ideologies.

- Define stereotype threat, and explain how it might influence scores on intelligence tests.

Intelligence is defined by the culture in which it exists. Most people in Western cultures tend to agree with the idea that intelligence is an important personality variable that should be admired in those who have it, but people from Eastern cultures tend to place less emphasis on individual intelligence and are more likely to view intelligence as reflecting wisdom and the desire to improve the society as a whole rather than only themselves (Baral & Das, 2004; Sternberg, 2007). In some cultures, it is seen as unfair and prejudicial to argue, even at a scholarly conference, that men and women might have different abilities in domains such as math and science and that these differences may be caused by context, environment, culture, and genetics. In short, although psychological tests accurately measure intelligence, a culture interprets the meanings of those tests and determines how people with differing levels of intelligence are treated.

Extremes of intelligence: Extremely low intelligence

One end of the distribution of intelligence scores is defined by people with very low IQ. Intellectual disability is a generalized disorder ascribed to people who have an IQ below 70, who have experienced deficits since childhood, and who have trouble with basic life skills, such as dressing and feeding themselves and communicating with others (Switzky & Greenspan, 2006). About 1% of the Canadian population, most of them males, fulfill the criteria for intellectual disability, but some children who are diagnosed as mentally disabled lose the classification as they get older and better learn to function in society. A particular vulnerability of people with low IQ is that they may be taken advantage of by others, and this is an important aspect of the definition of intellectual disability (Greenspan, Loughlin, & Black, 2001). Intellectual disability is divided into four categories: mild, moderate, severe, and profound. Severe and profound intellectual disabilities are usually caused by genetic mutations or accidents during birth, whereas mild forms have both genetic and environmental influences.

One cause of intellectual disability is Down syndrome, a chromosomal disorder caused by the presence of all or part of an extra 21st chromosome. The incidence of Down syndrome is estimated at one per 800 to 1,000 births, although its prevalence rises sharply in those born to older mothers (see Figure 9.7). People with Down syndrome typically exhibit a distinctive pattern of physical features, including a flat nose, upwardly slanted eyes, a protruding tongue, and a short neck.

Societal attitudes toward individuals with mental disabilities have changed over the past decades. We no longer use terms such as moron, idiot, or imbecile to describe these people, although these were the official psychological terms used to describe degrees of intellectual disability in the past. Laws, such as the Canadians with Disabilities Act, have made it illegal to discriminate on the basis of mental and physical disability, and there has been a trend to bring the mentally disabled out of institutions and into our workplaces and schools. In 2002, although capital punishment continues to be practised there, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the execution of people with an intellectual disability is “cruel and unusual punishment,” thereby ending the practice of their execution (Atkins v. Virginia, 2002). In Canada, capital punishment was abolished in 1976.

Extremes of intelligence: Extremely high intelligence

Having extremely high IQ is clearly less of a problem than having extremely low IQ, but there may also be challenges to being particularly smart. It is often assumed that schoolchildren who are labelled as gifted may have adjustment problems that make it more difficult for them to create social relationships. To study gifted children, Lewis Terman and Melita Oden (1959) selected about 1,500 high school students who scored in the top 1% on the Stanford-Binet and similar IQ tests (i.e., who had IQs of about 135 or higher), and tracked them for more than seven decades; the children became known as the “termites” and are still being studied today. This study found, first, that these students were not unhealthy or poorly adjusted but rather were above average in physical health and were taller and heavier than individuals in the general population. The students also had above average social relationships — for instance, being less likely to divorce than the average person (Seagoe, 1975).

Terman’s study also found that many of these students went on to achieve high levels of education and entered prestigious professions, including medicine, law, and science. Of the sample, 7% earned doctoral degrees, 4% earned medical degrees, and 6% earned law degrees. These numbers are all considerably higher than what would have been expected from a more general population. Another study of young adolescents who had even higher IQs found that these students ended up attending graduate school at a rate more than 50 times higher than that in the general population (Lubinski & Benbow, 2006).

As you might expect based on our discussion of intelligence, children who are gifted have higher scores on general intelligence (g), but there are also different types of giftedness. Some children are particularly good at math or science, some at automobile repair or carpentry, some at music or art, some at sports or leadership, and so on. There is a lively debate among scholars about whether it is appropriate or beneficial to label some children as gifted and talented in school and to provide them with accelerated special classes and other programs that are not available to everyone. Although doing so may help the gifted kids (Colangelo & Assouline, 2009), it also may isolate them from their peers and make such provisions unavailable to those who are not classified as gifted.

Sex differences in intelligence

As discussed in the introduction to to this chapter, Lawrence Summers’s claim about the reasons why women might be underrepresented in the hard sciences was based, in part, on the assumption that environment, such as the presence of gender discrimination or social norms, was important but also, in part, on the possibility that women may be less genetically capable of performing some tasks than are men. These claims, and the responses they provoked, provide another example of how cultural interpretations of the meanings of IQ can create disagreements and even guide public policy.

Assumptions about sex differences in intelligence are increasingly challenged in the research. In Canada, recent statistics show that women outnumber men in university degrees earned. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) released its Education at a Glance 2013 report where Canada ranked first among 34 OECD countries with adults who had attained a tertiary (i.e., post-secondary) education, reporting 51% of 25- to 64-year-olds in Canada attained a post-secondary education in 2011 (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2013). The report found women in Canada had significantly higher tertiary attainment rates compared with men, at 56% versus 46%, with a 16 percentage-point gap between the genders among younger adults.

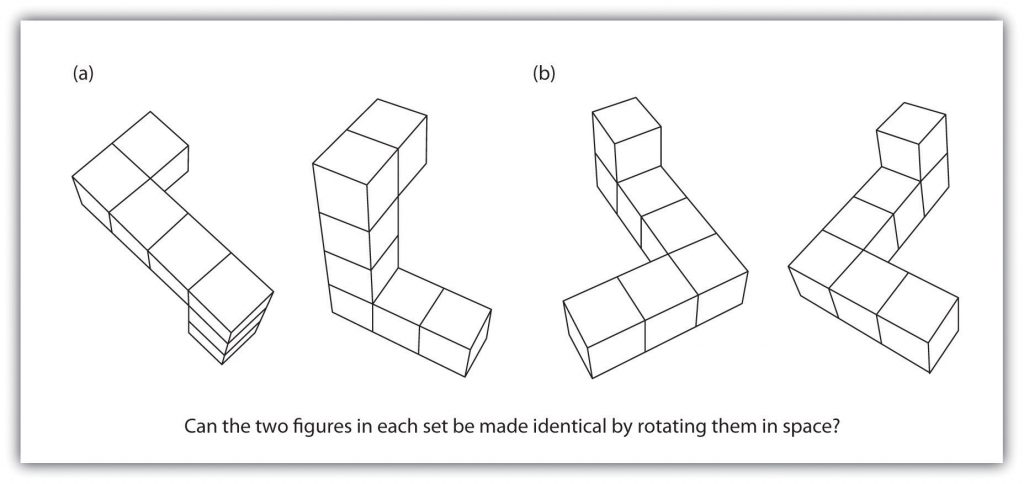

There are also observed sex differences on some particular types of tasks. Women tend to do better than men on some verbal tasks, including spelling, writing, and pronouncing words (Halpern et al., 2007), and they have better emotional intelligence in the sense that they are better at detecting and recognizing the emotions of others (McClure, 2000). On average, men do better than women on tasks requiring spatial ability (Voyer, Voyer, & Bryden, 1995), such as the mental rotation tasks (see Figure 9.8). Boys tend to do better than girls on both geography and geometry tasks (Vogel, 1996).

Although these differences are real, and can be important, keep in mind that like virtually all sex-group differences, the average difference between men and women is small compared with the average differences within each sex (Lynn & Irwing, 2004). There are many women who are better than the average man on spatial tasks, and many men who score higher than the average women in terms of emotional intelligence. Sex differences in intelligence allow us to make statements only about average differences and do not say much about any individual person.

The origins of sex differences in intelligence are not clear. Differences between men and women may be in part genetically determined, perhaps by differences in brain lateralization or by hormones (Kimura & Hampson, 1994; Voyer, Voyer, & Bryden, 1995), but nurture is also likely important (Newcombe & Huttenlocher, 2006). As infants, boys and girls show no or few differences in spatial or counting abilities, suggesting that the differences occur at least in part as a result of socialization (Spelke, 2005). Furthermore, the number of women entering the hard sciences has been increasing steadily over the past years, again suggesting that some of the differences may have been due to gender discrimination and societal expectations about the appropriate roles and skills of women.

Racial differences in intelligence

One of the most controversial and divisive areas of research in psychology has been to look for evidence of racial differences in intelligence (e.g., Lynn & Vanhanen, 2002; 2006). As you might imagine, this endeavour is fraught with methodological and theoretical minefields. Firstly, the concept of race as a biological category is problematic. Things like skin colour and facial features might define social or cultural conceptions of race but are biologically not very meaningful (Chou, 2017; Yudell, 2014). Secondly, intelligence interacts with a host of factors such as socioeconomic status and health; factors that are also related to race. Thirdly, intelligence tests themselves may be worded or administered in ways that favour the experiences of some groups, thus maximizing their scores, while failing to represent the experiences of other groups, thus lowering their scores.

In the United States, differences in the average scores of white and black Americans have been found consistently. For several decades, the source of this difference has been contentious, with some arguing that it must be genetic (e.g., Reich, 2018) with others arguing that it is nothing of the sort (e.g., Turkheimer, Harden, & Nisbett, 2017). The history of this controversy is interesting; for further reading, see William Saletan (2018) and Gavin Evans (2018). Interestingly, this debate among scholars is playing out in a nontraditional manner; as well as in scholarly journals, the debate has become more widely accessible due to the use of social and online media.

When average differences in intelligence have been observed between groups, these observations have, at times, led to discriminatory treatment of people from different races, ethnicities, and nationalities (Lewontin, Rose, & Kamin, 1984). One of the most egregious examples was the spread of eugenics, the proposal that one could improve the human species by encouraging or permitting reproduction of only those people with genetic characteristics judged desirable.

Eugenics became popular in Canada and the United States in the early 20th century and was supported by many prominent psychologists, including Sir Francis Galton (1822–1911). Dozens of universities offered courses in eugenics, and the topic was presented in most high school and university biology texts (Selden, 1999). Belief in the policies of eugenics led the Canadian legislatures in Alberta (1928) and British Columbia (1933) to pass sterilization laws that led to the forced sterilization of approximately 5000 people deemed to be “unfit.” Those affected were mainly youth and women, and people of Aboriginal or Metis identity were disproportionately targetted. This practice continued for several decades before being completely abandoned and the laws repealed. This dark chapter in Canadian history shows how intelligence testing can be used to justify political and racist ideology.

Research Focus

Stereotype threat

Although intelligence tests may not be culturally biased, the situation in which one takes a test may be. One environmental factor that may affect how individuals perform and achieve is their expectations about their ability at a task. In some cases, these beliefs may be positive, and they have the effect of making us feel more confident and thus better able to perform tasks. For instance, research has found that because Asian students are aware of the cultural stereotype that “Asians are good at math,” reminding them of this fact before they take a difficult math test can improve their performance on the test (Walton & Cohen, 2003).

On the other hand, sometimes these beliefs are negative, and they create negative self-fulfilling prophecies such that we perform more poorly just because of our knowledge about the stereotypes. Claude Steele and Joshua Aronson (1995) tested the hypothesis that the differences in performance on IQ tests between black and white Americans might be due to the activation of negative stereotypes. Because black students are aware of the stereotype that blacks are intellectually inferior to whites, this stereotype might create a negative expectation, which might interfere with their performance on intellectual tests through fear of confirming that stereotype.

In support of this hypothesis, the experiments revealed that black university students performed worse, in comparison to their prior test scores, on standardized test questions when this task was described to them as being diagnostic of their verbal ability, and thus when the stereotype was relevant, but that their performance was not influenced when the same questions were described as an exercise in problem solving. In another study, the researchers found that when black students were asked to indicate their race before they took a math test, again activating the stereotype, they performed more poorly than they had on prior exams, whereas white students were not affected by first indicating their race.

Researchers concluded that thinking about negative stereotypes that are relevant to a task that one is performing creates stereotype threat — that is, it creates performance decrements caused by the knowledge of cultural stereotypes. That is, they argued that the negative impact of race on standardized tests may be caused, at least in part, by the performance situation itself.

Research has found that stereotype threat effects can help explain a wide variety of performance decrements among those who are targeted by negative stereotypes. When stereotypes are activated, children with low socioeconomic status perform more poorly in math than do those with high socioeconomic status, and psychology students perform more poorly than do natural science students (Brown, Croizet, Bohner, Fournet, & Payne, 2003; Croizet & Claire, 1998). Even groups who typically enjoy advantaged social status can be made to experience stereotype threat. For example, white men perform more poorly on a math test when they are told that their performance will be compared with that of Asian men (Aronson, Lustina, Good, Keough, & Steele, 1999), and whites perform more poorly than blacks on a sport-related task when it is described to them as measuring their natural athletic ability (Stone, 2002; Stone, Lynch, Sjomeling, & Darley, 1999).

Research has found that stereotype threat is caused by both cognitive and emotional factors (Schmader, Johns, & Forbes, 2008). On the cognitive side, individuals who are experiencing stereotype threat show an increased vigilance toward the environment as well as increased attempts to suppress stereotypic thoughts. Engaging in these behaviours takes cognitive capacity away from the task. On the affective side, stereotype threat occurs when there is a discrepancy between our positive concept of our own skills and abilities and the negative stereotypes that suggest poor performance. These discrepancies create stress and anxiety, and these emotions make it harder to perform well on the task.

Stereotype threat is not, however, absolute; we can get past it if we try. What is important is to reduce the self doubts that are activated when we consider the negative stereotypes. Manipulations that affirm positive characteristics about the self or one’s social group are successful at reducing stereotype threat (Marx & Roman, 2002; McIntyre, Paulson, & Lord, 2003). In fact, just knowing that stereotype threat exists and may influence our performance can help alleviate its negative impact (Johns, Schmader, & Martens, 2005).

In summary, although there is no definitive answer to why IQ bell curves differ across racial and ethnic groups, and most experts believe that environment is important in pushing the bell curves apart, genetics can also be involved. It is important to realize that although IQ is heritable, this does not mean that group differences are caused by genetics. Although some people are naturally taller than others, since height is heritable, people who get plenty of nutritious food are taller than people who do not, and this difference is clearly due to environment. This is a reminder that group differences may be created by environmental variables but can also be reduced through appropriate environmental actions such as educational and training programs.

Key Takeaways

- Intellectual disability is a generalized disorder ascribed to people who have an IQ below 70, who have experienced deficits since childhood, and who have trouble with basic life skills, such as dressing and feeding themselves and communicating with others. One cause of intellectual disability is Down syndrome.

- Extremely intelligent individuals are not unhealthy or poorly adjusted, but rather are above average in physical health and taller and heavier than individuals in the general population.

- Men and women have almost identical intelligence, but men have more variability in their IQ scores than women do.

- On average, men do better than women on tasks requiring spatial ability, whereas women do better on verbal tasks and score higher on emotional intelligence.

- Although their bell curves overlap considerably, there are also average group differences for members of different racial and ethnic groups.

- The observed average differences in intelligence between racial and ethnic groups is controversial.

- The situation in which one takes a test may create stereotype threat, whereby performance decrements are caused by the knowledge of cultural stereotypes.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Were Lawrence Summers’s ideas about the potential causes of differences between men and women in math and hard sciences careers offensive to you? Why or why not?

- Do you think that we should give intelligence tests? Why or why not? Does it matter to you whether or not the tests have been standardized and shown to be reliable and valid?

- Give your ideas about the practice of providing accelerated classes to children listed as “gifted” in high school. What are the potential positive and negative outcomes of doing so? What research evidence has helped you form your opinion?

Image Attributions

Figure 9.7. Boy With Down Syndrome by Vanellus Foto is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license; My Special Daughter With Her Special Smile by Andreas-photography is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 9.8. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

Aronson, J., Lustina, M. J., Good, C., Keough, K., & Steele, C. M. (1999). When white men can’t do math: Necessary and sufficient factors in stereotype threat. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 29–46.

Atkins v. Virginia, 536 U.S. 304 (2002).

Baral, B. D., & Das, J. P. (2004). Intelligence: What is indigenous to India and what is shared? In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), International handbook of intelligence (pp. 270–301). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, R., Croizet, J.-C., Bohner, G., Fournet, M., & Payne, A. (2003). Automatic category activation and social behaviour: The moderating role of prejudiced beliefs. Social Cognition, 21(3), 167–193.

Chou, V. (2017, April, 17). How science and genetics are reshaping the race debate of the 21st century [Web log post]. Science in the News. Retrieved from http://sitn.hms.harvard.edu/flash/2017/science-genetics-reshaping-race-debate-21st-century

Colangelo, N., & Assouline, S. (2009). Acceleration: Meeting the academic and social needs of students. In T. Balchin, B. Hymer, & D. J. Matthews (Eds.), The Routledge international companion to gifted education (pp. 194–202). New York, NY: Routledge.

Croizet, J.-C., & Claire, T. (1998). Extending the concept of stereotype and threat to social class: The intellectual underperformance of students from low socioeconomic backgrounds. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(6), 588–594.

Evans, G. (2018, March 2). The unwelcome revival of ‘race science.’ The Guardian: The Long Read. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/02/the-unwelcome-revival-of-race-science

Greenspan, S., Loughlin, G., & Black, R. S. (2001). Credulity and gullibility in people with developmental disorders: A framework for future research. In L. M. Glidden (Ed.), International review of research in mental retardation (Vol. 24, pp. 101–135). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Halpern, D. F. (1992). Sex differences in cognitive abilities (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Halpern, D. F., Benbow, C. P., Geary, D. C., Gur, R. C., Hyde, J. S., & Gernsbache, M. A. (2007). The science of sex differences in science and mathematics. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 8(1), 1–51.

Johns, M., Schmader, T., & Martens, A. (2005). Knowing is half the battle: Teaching stereotype threat as a means of improving women’s math performance. Psychological Science, 16(3), 175–179.

Kimura, D., & Hampson, E. (1994). Cognitive pattern in men and women is influenced by fluctuations in sex hormones. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 3(2), 57–61.

Lewontin, R. C., Rose, S. P. R., & Kamin, L. J. (1984). Not in our genes: Biology, ideology, and human nature (1st ed.). New York, NY: Pantheon Books.

Lubinski, D., & Benbow, C. P. (2006). Study of mathematically precocious youth after 35 years: Uncovering antecedents for the development of math-science expertise. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(4), 316–345.

Lynn, R., & Irwing, P. (2004). Sex differences on the progressive matrices: A meta-analysis. Intelligence, 32(5), 481–498.

Lynn, R. & Vanhanen, T. (2002). IQ and the wealth of nations. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Lynn, R. & Vanhanen, T. (2006). IQ and global inequality. Augusta, GA: Washington Summit Publishers.

Marx, D. M., & Roman, J. S. (2002). Female role models: Protecting women’s math test performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(9), 1183–1193.

McClure, E. B. (2000). A meta-analytic review of sex differences in facial expression processing and their development in infants, children, and adolescents. Psychological Bulletin, 126(3), 424–453.

McIntyre, R. B., Paulson, R. M., & Lord, C. G. (2003). Alleviating women’s mathematics stereotype threat through salience of group achievements. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39(1), 83–90.

Newcombe, N. S., & Huttenlocher, J. (2006). Development of spatial cognition. In D. Kuhn, R. S. Siegler, W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Cognition, perception, and language (6th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 734–776). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. (2013). Education at a glance 2013: OECD indicators. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/edu/eag2013%20(eng)–FINAL%2020%20June%202013.pdf

Reich, D. (2018, March 23). How genetics is changing our understanding of ‘race.’ The New York Times: Opinion. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/23/opinion/sunday/genetics-race.html

Saletan, W. (2018, April 27). Stop talking about race and IQ [Web log post]. Slate. Retrieved from https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2018/04/stop-talking-about-race-and-iq-take-it-from-someone-who-did.html

Schmader, T., Johns, M., & Forbes, C. (2008). An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Psychological Review, 115(2), 336–356.

Seagoe, M. V. (1975). Terman and the gifted. Los Altos, CA: William Kaufmann.

Selden, S. (1999). Inheriting shame: The story of eugenics and racism in America. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Spelke, E. S. (2005). Sex differences in intrinsic aptitude for mathematics and science? A critical review. American Psychologist, 60(9), 950–958.

Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 797–811.

Sternberg, R. J. (2007). Intelligence and culture. In S. Kitayama & D. Cohen (Eds.), Handbook of cultural psychology (pp. 547–568). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Stone, J. (2002). Battling doubt by avoiding practice: The effects of stereotype threat on self-handicapping in white athletes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(12), 1667–1678.

Stone, J., Lynch, C. I., Sjomeling, M., & Darley, J. M. (1999). Stereotype threat effects on black and white athletic performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1213–1227.

Switzky, H. N., & Greenspan, S. (2006). What is mental retardation? Ideas for an evolving disability in the 21st century. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation.

Terman, L. M., & Oden, M. H. (1959). Genetic studies of genius: The gifted group at mid-life (Vol. 5). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Turkheimer, E., Harden, K. P., Nisbett, R. E. (2017). There’s still no good reason to believe black-white IQ differences are due to genes. Vox: The Big Idea. Retrieved from https://www.vox.com/the-big-idea/2017/6/15/15797120/race-black-white-iq-response-critics

Vogel, G. (1996). School achievement: Asia and Europe top in world, but reasons are hard to find. Science, 274(5291), 1296.

Voyer, D., Voyer, S., & Bryden, M. P. (1995). Magnitude of sex differences in spatial abilities: A meta-analysis and consideration of critical variables. Psychological Bulletin, 117(2), 250–270.

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2003). Stereotype lift. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39(5), 456–467.

Yudell, M. (2014). Race unmasked; Biology and race in the 20th century. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.