6.0 Introduction

Research Focus

The sad tale of Little Albert

The boy known as Little Albert was an 11-month-old child when two psychologists, John Watson and Rosalie Raynor, created a situation that would force him to “learn” fear at the sight of a white rat, an animal he was not scared of before the research took place (Watson & Raynor, 1920). They accomplished this by exploiting the fear and aversion that babies have naturally to loud noises: Watson and Raynor hit a steel bar with a hammer whenever they showed the white rat to Little Albert. The fear that Albert felt at the loud noise became associated with the white rat, and poor Little Albert then became afraid of white rats and indeed, of any white furry objects. Needless to say, this research violates a number of ethical standards and would never be permitted today. It is, however, an unfortunate case study of the ease with which it is possible to “learn” something and also an example of how learning includes a variety of processes besides those that we traditionally think of like studying or practising.

The topic of this chapter is learning — the relatively permanent change in knowledge or behaviour that is the result of experience. You might think of learning in terms of what you need to do before an upcoming exam, the knowledge that you take away from your classes, or new skills that you acquire through practise, but this chapter will show you that learning can involve several different processes.

Learning is perhaps the most important human capacity. Learning allows us to create effective lives by being able to respond to changes. We learn to avoid touching hot stoves, to find our way home from school, and to remember which people have helped us in the past and which people have been unkind. Without the ability to learn from our experiences, our lives would be remarkably dangerous and inefficient. The principles of learning can also be used to explain a wide variety of social interactions, including social dilemmas in which people make important, and often selfish, decisions about how to behave by calculating the costs and benefits of different outcomes.

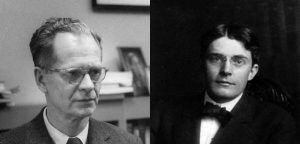

The study of learning is closely associated with the behaviourist school of psychology, in which it was seen as an alternative scientific perspective to the failure of introspection. The behaviourists, including B. F. Skinner and John Watson (see Figure 6.1), focused their research entirely on behaviour, to the exclusion of any kinds of mental processes. For behaviourists, the fundamental aspect of learning is the process of conditioning — the ability to connect stimuli (i.e., the changes that occur in the environment) with responses (i.e., behaviours or other actions).

However, conditioning is just one type of learning. We will also consider other types, including learning through insight, as well as observational learning, which is also known as modelling. In each case, we will see not only what psychologists have learned about the topics, but also the important influence that learning has on many aspects of our everyday lives.

Image Attributions

Figure 6.1. B. F. Skinner at Harvard Circa 1950 by Silly rabbit is used under a CC BY 3.0 license; John Broadus Watson by unknown author is in the public domain.

References

Watson, J. B., & Rayner, R. R. (1920). Conditioned emotional reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 3, 1–14.