8.1 The Elements of Cognition

Learning Objectives

- Understand the problems with attempting to define categories.

- Understand typicality and fuzzy category boundaries.

- Learn about theories of the mental representation of concepts.

- Learn how knowledge may influence concept learning.

- Understand how we use schemas to mentally represent knowledge.

Consider the following set of objects: some dust, papers, a computer monitor, two pens, a cup, and an orange. What do these things have in common? Only that they all happen to be on my desk as I write this. This set of things can be considered a category, a set of objects that can be treated as equivalent in some way. However, most of our categories seem much more informative; they share many properties. For example, consider the following categories: trucks, wireless devices, weddings, psychopaths, and trout. Although the objects in a given category are different from one another, they have many commonalities. When you know something is a truck, you know quite a bit about it. The psychology of categories concerns how people learn, remember, and use informative categories such as trucks or psychopaths.

The mental representations we form of categories are called concepts. There is a category of trucks in the world, and I also have a concept of trucks in my head. We assume that people’s concepts correspond more or less closely to the actual category, but it can be useful to distinguish the two, as when someone’s concept is not really correct.

Concepts are at the core of intelligent behaviour. We expect people to be able to know what to do in new situations and when confronting new objects. If you go into a new classroom and see chairs, a blackboard, a projector, and a screen, you know what these things are and how they will be used. You’ll sit on one of the chairs and expect the instructor to write on the blackboard or project something onto the screen. You do this even if you have never seen any of these particular objects before, because you have concepts of classrooms, chairs, projectors, and so forth, that tell you what they are and what you’re supposed to do with them. Furthermore, if someone tells you a new fact about the projector — for example, that it has a halogen bulb — you are likely to extend this fact to other projectors you encounter. In short, concepts allow you to extend what you have learned about a limited number of objects to a potentially infinite set of entities.

You know thousands of categories, most of which you have learned without careful study or instruction. Although this accomplishment may seem simple, we know that it isn’t, because it is difficult to program computers to solve such intellectual tasks. If you teach a learning program that a robin, a swallow, and a duck are all birds, it may not recognize a cardinal or peacock as a bird. As we’ll shortly see, the problem is that objects in categories are often surprisingly diverse.

Simpler organisms, such as animals and human infants, also have concepts (Mareschal, Quinn, & Lea, 2010). Squirrels may have a concept of predators, for example, that is specific to their own lives and experiences. However, animals likely have many fewer concepts and cannot understand complex concepts, such as mortgages or musical instruments.

Nature of categories

Traditionally, it has been assumed that categories are well-defined. This means that you can give a definition that specifies what is in and out of the category. Such a definition has two parts. First, it provides the necessary features for category membership; what must objects have in order to be in it? Second, those features must be jointly sufficient for membership; if an object has those features, then it is in the category. For example, if a dog is defined as a four-legged animal that barks, this would mean that every dog is four-legged, an animal, and barks, and also that anything that has all those properties is a dog.

Unfortunately, it has not been possible to find definitions for many familiar categories. Definitions are neat and clear-cut, but the world is messy and often unclear. For example, consider our definition of dogs. In reality, not all dogs have four legs, and not all dogs bark. Some dogs lose their bark with age, which might be seen as an improvement for some, but no one would doubt that a barkless dog is still a dog. It is often possible to find some necessary features (e.g., all dogs have blood and breathe), but these features are generally not sufficient to determine category membership (e.g., you also have blood and breathe but are not a dog).

Even in domains where one might expect to find clear-cut definitions, such as science and law, there are often problems. For example, many people were upset when Pluto was downgraded from its status as a planet to a dwarf planet in 2006. Upset turned to outrage when they discovered that there was no hard-and-fast definition of planethood: “Aren’t these astronomers scientists? Can’t they make a simple definition?” In fact, they couldn’t. After an astronomical organization tried to make a definition for planets, a number of astronomers complained that it might not include accepted planets such as Neptune and refused to use it. If everything looked like our planet, our moon, and our sun, it would be easy to give definitions of planets, moons, and stars, but the universe has sadly not conformed to this ideal.

Borderline items

Experiments also showed that the psychological assumptions of well-defined categories were not correct. James Hampton (1979) asked subjects to judge whether a number of items were in different categories. Hampton did not find that items were either clear members or clear nonmembers. Instead, many items were just barely considered category members and others were just barely not members, with much disagreement among subjects. Sinks were barely included as members of the kitchen utensil category, and sponges were barely excluded. People just included seaweed as a vegetable and just barely excluded tomatoes and gourds. Hampton found that members and nonmembers formed a continuum, with no obvious break in people’s membership judgments. If categories were well defined, such examples should be very rare. Many studies since then have found such borderline members that are not clearly in or clearly out of the category.

Michael McCloskey and Sam Glucksberg (1978) found further evidence for borderline membership by asking people to judge category membership twice, separated by two weeks. They found that when people made repeated category judgments — such as “Is an olive a fruit?” or “Is a sponge a kitchen utensil?” — they changed their minds about borderline items, up to 22% of the time. So, not only do people disagree with one another about borderline items, they disagree with themselves! As a result, researchers often say that categories are fuzzy, that is, they have unclear boundaries that can shift over time.

Typicality

A related finding that turns out to be most important is that even among items that clearly are in a category, some seem to be “better” members than others (Rosch, 1973). Among birds, for example, robins and sparrows are very typical. In contrast, ostriches and penguins are very atypical, meaning not typical. If someone says, “There’s a bird in my yard,” the image you have will likely be of a smallish, passerine bird, such as a robin, and probably not an eagle, hummingbird, or turkey.

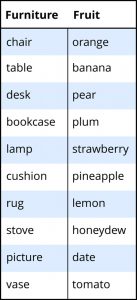

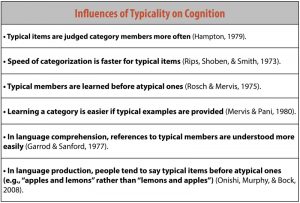

You can find out which category members are typical merely by asking people. Category members may be listed in order of their rated typicality (see Figure 8.3). Typicality is perhaps the most important variable in predicting how people interact with categories, but there are other influences of typicality (see Figure 8.4).

We can understand the two phenomena of borderline members and typicality as two sides of the same coin. Think of the most typical category member; this is often called the category prototype. Items that are less and less similar to the prototype become less and less typical. At some point, these less typical items become so atypical that you start to doubt whether they are in the category at all. Is a rug really an example of furniture? It’s in the home like chairs and tables, but it’s also different from most furniture in its structure and use. From day to day, you might change your mind as to whether this atypical example is in or out of the category. So, changes in typicality ultimately lead to borderline members.

Source of typicality

Intuitively, it is not surprising that robins are better examples of birds than penguins are or that a table is a more typical kind of furniture than a rug is. However, given that robins and penguins are known to be birds, why should one be more typical than the other? One possible answer is the frequency with which we encounter the object. We see a lot more robins than penguins, so they must be more typical. Frequency does have some effect, but it is actually not the most important variable (Rosch, Simpson, & Miller, 1976). For example, one may see both rugs and tables every single day, but one of them is much more typical as furniture than the other.

The best account of what makes something typical comes from the family resemblance theory, which proposes that items are likely to be typical if they have the features that are frequent in the category and do not have features frequent in other categories (Rosch & Mervis, 1975). Let’s compare two extremes: robins and penguins. Robins are small flying birds that sing, live in nests in trees, migrate in winter, hop around on your lawn, and so on. Most of these properties are found in many other birds. In contrast, penguins do not fly, do not sing, do not live in nests nor in trees, and do not hop around on your lawn. Furthermore, they have properties that are common in other categories, such as swimming expertly and having wings that look and act like fins. These properties are more often found in fish than in birds.

According to the family resemblance theory, it is not because a robin is a very common bird that makes it typical. Rather, it is because the robin has the shape, size, body parts, and behaviours that are very common among birds — and not common among fish, mammals, bugs, and so forth.

In a classic experiment, Eleanor Rosch and Carolyn Mervis (1975) made up two new categories, each with arbitrary features. Subjects viewed example after example and had to learn which example was in which category. Rosch and Mervis constructed some items that had features that were common in the category and other items that had features less common in the category. The subjects learned the first type of item before they learned the second type. Furthermore, they then rated the items with common features as more typical. In another experiment, Rosch and Mervis constructed items that differed in how many features were shared with a different category. The more features that were shared, the longer it took subjects to learn which category the item was in. These experiments, and many later studies, support both parts of the family resemblance theory.

Category hierarchies

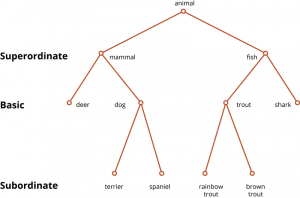

Many important categories fall into hierarchies, in which more concrete categories are nested inside larger, abstract categories. For example, consider the following categories: brown bear, bear, mammal, vertebrate, animal, and entity. Clearly, all brown bears are bears, all bears are mammals, all mammals are vertebrates, and so on. Any given object typically does not fall into just one category; it could be in a dozen different categories, some of which are structured in this hierarchical manner. Examples of biological categories come to mind most easily, but within the realm of human artifacts, hierarchical structures can readily be found, as in the following categories: desk chair, chair, furniture, artifact, and object.

Roger Brown (1958), a child language researcher, was perhaps the first to note that there seems to be a preference for which category we use to label things. If your office desk chair is in the way, you’ll probably say, “Move that chair,” rather than, “Move that desk chair” or “piece of furniture.” Brown thought that the use of a single, consistent name probably helped children to learn the name for things. Indeed, children’s first labels for categories tend to be exactly those names that adults prefer to use (Anglin, 1977).

This preference is referred to as a preference for the basic level of categorization, and it was first studied in detail by Eleanor Rosch and her students (Rosch, Mervis, Gray, Johnson, & Boyes-Braem, 1976). The basic level represents a kind of Goldilocks effect in which the category used for something is not too small (e.g., northern brown bear) and not too big (e.g., animal), but it is just right (e.g., bear). The simplest way to identify an object’s basic-level category is to discover how it would be labelled in a neutral situation. Rosch and her students showed subjects pictures and asked them to provide the first name that came to mind. They found that 1,595 names were at the basic level, with 14 more specific names (i.e., subordinates) used. Only once did anyone use a more general name (i.e., superordinate). Furthermore, in printed text, basic-level labels are much more frequent than most subordinate or superordinate labels (e.g., Wisniewski & Murphy, 1989).

The preference for the basic level is not merely a matter of labelling. Basic-level categories are usually easier to learn. As such, people are faster at identifying objects as members of basic-level categories (Rosch, Mervis et al., 1976).

As Brown noted (1958), children use these categories first in language learning, and superordinates are especially difficult for children to fully acquire. This is a controversial claim, as some say that infants learn superordinates before anything else (Mandler, 2004). However, if true, then it is very puzzling that older children have great difficulty learning the correct meaning of words for superordinates, as well as in learning artificial superordinate categories (Horton & Markman, 1980; Mervis, 1987). As a result, it seems fair to say that the answer to this question is not yet fully known.

Rosch and colleagues (Rosch, Mervis et al., 1976) initially proposed that basic-level categories cut the world at its joints, that is, merely reflect the big differences between categories like chairs and tables or between cats and mice that exist in the world. However, it turns out that which level is basic is not universal. North Americans are likely to use names like “tree,” “fish,” and “bird” to label natural objects, but people in less industrialized societies seldom use these labels and instead use more specific words, equivalent to “elm,” “trout,” and “finch” (Berlin, 1992). Because Americans and many other people living in industrialized societies know so much less than our ancestors did about the natural world, our basic level has moved up to what would have been the superordinate level a century ago. Furthermore, experts in a domain often have a preferred level that is more specific than that of non-experts. For example, birdwatchers see sparrows rather than just birds, and carpenters see roofing hammers rather than just hammers (Tanaka & Taylor, 1991). This all suggests that the preferred level is not only based on how different categories are in the world, but that people’s knowledge and interest in the categories has an important effect.

One explanation of the basic-level preference is that basic-level categories are more differentiated. The category members are similar to one another, but they are different from members of other categories (Murphy & Brownell, 1985; Rosch, Mervis et al., 1976). The alert reader will note a similarity to the explanation of typicality provided above. However, here we are talking about the entire category and not individual members. Chairs are pretty similar to one another, sharing a lot of features (e.g., legs, a seat, a back, similar size and shape, etc.), and they also do not share that many features with other furniture. Superordinate categories are not as useful because their members are not very similar to one another. What features are common to most furniture? There are very few. Subordinate categories are not as useful because they are very similar to other categories. For example, desk chairs are quite similar to dining room chairs and easy chairs. As a result, it can be difficult to decide which subordinate category an object is in (Murphy & Brownell, 1985). Experts can differ from novices, using categories that are more differentiated, because they know different things about the categories, therefore changing how similar the categories are.

Theories of concept representation

Now that we know these facts about the psychology of concepts, the question arises of how concepts are mentally represented. There have been two main answers. The first, somewhat confusingly called the prototype theory, suggests that people have a summary representation of the category, a mental description that is meant to apply to the category as a whole. The significance of summary will become apparent when the next theory is described. This description can be represented as a set of weighted features (Smith & Medin, 1981). The features are weighted by their frequency in the category. For the category of birds, having wings and feathers would have a very high weight; eating worms would have a lower weight; living in Antarctica would have a lower weight still, but not zero, as some birds do live there.

The idea behind prototype theory is that when you learn a category, you learn a general description that applies to the category as a whole. For example, birds have wings and usually fly, some eat worms, and some swim underwater to catch fish. People can state these generalizations, and sometimes we learn about categories by reading or hearing such statements as “The komodo dragon can grow to be 10 feet long.”

When you try to classify an item, you see how well it matches that weighted list of features. For example, if you saw something with wings and feathers fly onto your front lawn and eat a worm, you could unconsciously consult your concepts and see which ones contained the features you observed. This example possesses many of the highly weighted bird features, so it should be easy to identify as a bird.

This theory readily explains the phenomena we discussed earlier. Typical category members have more, or higher-weighted, features. Therefore, it is easier to match them to your conceptual representation. In contrast, less typical items have fewer, or lower-weighted, features, and they may have features of other concepts. Therefore, they don’t match your representation as well. This makes people less certain in classifying such items. Borderline items may have features in common with multiple categories or not be very close to any of them. For example, edible seaweed does not have many of the common features of vegetables but also is not close to any other food concept — such as meat, fish, fruit, and so on — making it hard to know what kind of food it is.

A very different account of concept representation is the exemplar theory, with the word exemplar simply being a fancy name for an example (Medin & Schaffer, 1978). This theory denies that there is a summary representation. Instead, the theory claims that your concept of vegetables is remembered examples of vegetables you have seen. This could of course be hundreds or thousands of exemplars over the course of your life, though we don’t know for sure how many exemplars you actually remember.

How does this theory explain classification? When you see an object, you unconsciously compare it to the exemplars in your memory, and you judge how similar it is to exemplars in different categories. For example, if you see some object on your plate and want to identify it, it will probably activate memories of vegetables, meats, fruit, and so on. In order to categorize this object, you calculate how similar it is to each exemplar in your memory. These similarity scores are added up for each category. Perhaps the object is very similar to a large number of vegetable exemplars, moderately similar to a few fruit, and only minimally similar to some exemplars of meat you remember. These similarity scores are compared, and the category with the highest score is chosen. That being said, the decision of which category is chosen is more complex than this, but the full details are beyond this discussion.

Why would someone propose such a theory of concepts? One answer is that in many experiments studying concepts, people learn concepts by seeing exemplars over and over again until they learn to classify them correctly. Under such conditions, it seems likely that people eventually memorize the exemplars (Smith & Minda, 1998). There is also evidence that close similarity to well-remembered objects has a large effect on classification. Scott Allen and Lee Brooks (1991) taught people to classify items by following a rule. However, they also had their subjects study the items, which were richly detailed. In a later test, the experimenters gave people new items that were very similar to one of the old items but were in a different category. That is, they changed one property so that the item no longer followed the rule. They discovered that people were often fooled by such items. Rather than following the category rule they had been taught, they seemed to recognize the new item as being very similar to an old one and so put it, incorrectly, into the same category.

Many experiments have been done to compare the prototype and exemplar theories. Overall, the exemplar theory seems to have won most of these comparisons. However, the experiments are somewhat limited in that they usually involve a small number of exemplars that people view over and over again. It is not so clear that exemplar theory can explain real-world classification in which people do not spend much time learning individual items (e.g., how much time do you spend studying squirrels or chairs?). Also, given that some part of our knowledge of categories is learned through general statements we read or hear, it seems that there must be room for a summary description separate from exemplar memory.

Many researchers would now acknowledge that concepts are represented through multiple cognitive systems. For example, your knowledge of dogs may be in part through general descriptions such as “dogs have four legs,” but you probably also have strong memories of some exemplars, such as your family dog or other dogs you have known before, that influence your categorization. Furthermore, some categories also involve rules (e.g., a strike in baseball). How these systems work together is the subject of current study.

Knowledge

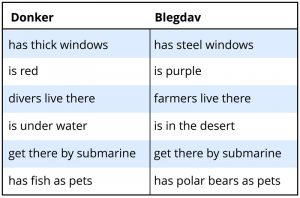

The final topic has to do with how concepts fit with our broader knowledge of the world. We have been talking very generally about people learning the features of concepts. For example, they see a number of birds and then learn that birds generally have wings, or perhaps they remember bird exemplars. From this perspective, it makes no difference what those exemplars or features are — people just learn them. However, consider two possible concepts of buildings and their features (see Figure 8.8).

Imagine you had to learn these two concepts by seeing exemplars of them, each exemplar having some of the features listed for the concept as well as some idiosyncratic features. Learning the donker concept would be pretty easy. It seems to be a kind of underwater building, perhaps for deep-sea explorers. Its features seem to go together. In contrast, the blegdav doesn’t really make sense. If it is in the desert, how can you get there by submarine, and why do they have polar bears as pets? Why would farmers live in the desert or use submarines? What good would steel windows do in such a building? This concept seems peculiar. In fact, if people are asked to learn new concepts that make sense, such as donkers, they learn them quite a bit faster than concepts such as blegdavs that don’t make sense (Murphy & Allopenna, 1994). Furthermore, the features that seem connected to one another, such as being underwater and getting there by submarine, are learned better than features that do not seem related to the others, such as being red.

Such effects demonstrate that when we learn new concepts, we try to connect them to the knowledge we already have about the world. If you were to learn about a new animal that does not seem to eat or reproduce, you would be very puzzled and think that you must have gotten something wrong. By themselves, the prototype and exemplar theories do not predict this. They simply say that you learn descriptions or exemplars, and they do not put any constraints on what those descriptions or exemplars are. However, the knowledge approach to concepts emphasizes that concepts are meant to tell us about real things in the world, and so our knowledge of the world is used in learning and thinking about concepts.

We can see this effect of knowledge when we learn about new pieces of technology. For example, most people could easily learn about tablet computers (e.g., iPads) when they were first introduced by drawing on their knowledge of laptops, cell phones, and related technology. Of course, this reliance on past knowledge can also lead to errors, as when people don’t learn about features of their new tablet that weren’t present in their cell phone or expect the tablet to be able to do something it can’t.

Schemas are a way for us to cognitively organize the knowledge that we have amassed about specific things: people, activities, categories, events, and so on. For example, you may have a complex and highly detailed schema about using an iPad if you have a lot of experience. Your knowledge about using it is organized, and integrating new knowledge (e.g., using a new app) is likely to be much easier than it is for someone whose schema is limited to the basics. Schemas provide a cognitive structure for us to organize and use knowledge; for example, your schema for what to do on a first date is likely to be affected by things like your age, cultural background, experience, and so on. Schemas are cognitive, but they interact with feelings and behaviour. We will return to schema later in this chapter.

Establishing concepts

Concepts are central to our everyday thought. When we are planning for the future or thinking about our past, we think about specific events and objects in terms of their categories. If you’re visiting a friend with a new baby, you have some expectations about what the baby will do, what gifts would be appropriate, how you should behave toward it, and so on. Knowing about the category of babies helps you to effectively plan and behave when you encounter this child you’ve never seen before.

Learning about those categories is a complex process that involves seeing exemplars (e.g., babies), hearing or reading general descriptions (e.g., “babies like black-and-white pictures”), general knowledge (e.g., babies have kidneys), and learning the occasional rule (e.g., all babies have a rooting reflex). Current research is focusing on how these different processes take place in the brain. It seems likely that these different aspects of concepts are accomplished by different neural structures (Maddox & Ashby, 2004).

Another interesting topic is how concepts differ across cultures. As different cultures have different interests and different kinds of interactions with the world, it seems clear that their concepts will somehow reflect those differences. On the other hand, the structure of categories in the world also imposes a strong constraint on what kinds of categories are actually useful. Some researchers have suggested that differences between Eastern and Western modes of thought have led to qualitatively different kinds of concepts (e.g., Norenzayan, Smith, Kim, & Nisbett, 2002). Although such differences are intriguing, we should also remember that different cultures seem to share common categories such as chairs, dogs, parties, and jars, so the differences may not be as great as suggested by experiments designed to detect cultural effects. The interplay of culture, the environment, and basic cognitive processes in establishing concepts has yet to be fully investigated.

Source: Adapted from Murphy (2020).

Key Takeaways

- Categories are sets of equivalent objects, but they are not always well-defined.

- The mental representations of categories are called concepts. Concepts allow us to behave intelligently in new situations. They involve prototypes and exemplars.

- Some category members are seen as prototypical.

- Many categories fall into hierarchies. Basic categories are more likely to be used.

- We build on existing knowledge when learning new concepts.

- Schemas are organized knowledge structures

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Pick a couple of familiar categories, and try to come up with definitions for them. When you evaluate each proposal, consider whether it is, in fact, accurate as a definition and if it is a definition that people might actually use in identifying category members.

- For the same categories, can you identify members that seem to be “better” and “worse” members? What about these items makes them typical and atypical?

- Look around the room. Point to some common objects, including things people are wearing or brought with them, and identify what the basic-level category is for that item. What are superordinate and subordinate categories for the same items?

- Draw an image that represents your schema for doing laundry. Then, do the same thing for studying for a final exam. What have you included in your studying schema?

Image Attributions

Figure 8.1. Yellow and Red Drop Side Truck by unknown author is used under a CC0 license.

Figure 8.2. Hemi – In His Harness by State Farm is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 8.3. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 8.4. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 8.5. Japanese Robin by unknown author is used under a CC0 license.

Figure 8.6. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 8.7. The Komodo Dragon by Adhi Rachdian is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 8.8. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

Allen, S. W., & Brooks, L. R. (1991). Specializing the operation of an explicit rule. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 120, 3–19.

Anglin, J. M. (1977). Word, object, and conceptual development. New York, NY: Norton.

Berlin, B. (1992). Ethnobiological classification: Principles of categorization of plants and animals in traditional societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Brown, R. (1958). How shall a thing be called? Psychological Review, 65, 14–21.

Garrod, S., & Sanford, A. (1977). Interpreting anaphoric relations: The integration of semantic information while reading. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 16(1), 77–90.

Hampton, J. A. (1979). Polymorphous concepts in semantic memory. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 18, 441–461.

Horton, M. S., & Markman, E. M. (1980). Developmental differences in the acquisition of basic and superordinate categories. Child Development, 51, 708–719.

Maddox, W. T., & Ashby, F. G. (2004). Dissociating explicit and procedural-based systems of perceptual category learning. Behavioural Processes, 66, 309–332.

Mandler, J. M. (2004). The foundations of mind: Origins of conceptual thought. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Mareschal, D., Quinn, P. C., & Lea, S. E. G. (Eds.). (2010). The making of human concepts. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

McCloskey, M. E., & Glucksberg, S. (1978). Natural categories: Well defined or fuzzy sets? Memory & Cognition, 6, 462–472.

Medin, D. L., & Schaffer, M. M. (1978). Context theory of classification learning. Psychological Review, 85, 207–238.

Mervis, C. B. (1987). Child-basic object categories and early lexical development. In U. Neisser (Ed.), Concepts and conceptual development: Ecological and intellectual factors in categorization (pp. 201–233). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Mervis, C. B., & Pani, J. R. (1980). Acquisition of basic object categories. Cognitive Psychology, 12(4), 496–522.

Murphy, G. L. (2020). Categories and concepts. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF. Retrieved from http://noba.to/6vu4cpkt

Murphy, G. L., & Allopenna, P. D. (1994). The locus of knowledge effects in concept learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 20, 904–919.

Murphy, G. L., & Brownell, H. H. (1985). Category differentiation in object recognition: Typicality constraints on the basic category advantage. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 11, 70–84.

Norenzayan, A., Smith, E. E., Kim, B. J., & Nisbett, R. E. (2002). Cultural preferences for formal versus intuitive reasoning. Cognitive Science, 26, 653–684.

Onishi, K., Murphy, G., & Bock, K. (2008). Prototypicality in sentence production. Cognitive psychology, 56(2), 103-141.

Rips, L. J., Shoben, E. J., & Smith E. E. (1973). Semantic distance and the verification of semantic distance. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 12(1), 1–20.

Rosch, E. (1973). On the internal structure of perceptual and semantic categories. In T. E. Moore (Ed.), Cognitive development and the acquisition of language (pp. 111–144). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Rosch, E., & Mervis, C. B. (1975). Family resemblance: Studies in the internal structure of categories. Cognitive Psychology, 7, 573–605.

Rosch, E., Mervis, C. B., Gray, W., Johnson, D., & Boyes-Braem, P. (1976). Basic objects in natural categories. Cognitive Psychology, 8, 382–439.

Rosch, E., Simpson, C., & Miller, R. S. (1976). Structural bases of typicality effects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 2, 491–502.

Smith, E. E., & Medin, D. L. (1981). Categories and concepts. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Smith, J. D., & Minda, J. P. (1998). Prototypes in the mist: The early epochs of category learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 24, 1411–1436.

Tanaka, J. W., & Taylor, M. E. (1991). Object categories and expertise: Is the basic level in the eye of the beholder? Cognitive Psychology, 15, 121–149.

Wisniewski, E. J., & Murphy, G. L. (1989). Superordinate and basic category names in discourse: A textual analysis. Discourse Processes, 12, 245–261.