15.3 Anxiety and Related Disorders

Learning Objectives

- Understand the relationship between anxiety and anxiety disorders.

- Identify key vulnerabilities for developing anxiety and related disorders.

- Identify main diagnostic features of specific anxiety-related disorders.

- Differentiate between disordered and non-disordered functioning.

Anxiety, the nervousness or agitation that we sometimes experience, often about something that is going to happen, is a natural part of life. We all feel anxious at times, maybe when we think about our upcoming visit to the dentist or the presentation we have to give to our class next week. Anxiety is an important and useful human emotion; it is associated with the activation of the sympathetic nervous system and the physiological and behavioural responses that help protect us from danger. However, too much anxiety can be debilitating, and every year millions of people suffer from anxiety disorders, which are psychological disturbances marked by irrational fears, often of everyday objects and situations (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005). Primary anxiety-related diagnoses include generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, specific phobia, social anxiety disorder or social phobia, post traumatic stress disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. In this section, we summarize the main clinical features of each of these disorders and discuss their similarities and differences with everyday experiences of anxiety.

If anxiety begins to interfere in the person’s life in a significant way, it is considered a disorder. Anxiety and closely related disorders emerge from “triple vulnerabilities,” a combination of biological, psychological, and specific factors that increase our risk for developing a disorder (Barlow, 2002; Suárez, Bennett, Goldstein, & Barlow, 2009). Biological vulnerabilities refer to specific genetic and neurobiological factors that might predispose someone to develop anxiety disorders. No single gene directly causes anxiety or panic, but our genes may make us more susceptible to anxiety and influence how our brains react to stress (Drabant et al., 2012; Gelernter & Stein, 2009; Smoller, Block, & Young, 2009). Psychological vulnerabilities refer to the influences that our early experiences have on how we view the world. If we were confronted with unpredictable stressors or traumatic experiences at younger ages, we may come to view the world as unpredictable and uncontrollable, even dangerous (Chorpita & Barlow, 1998; Gunnar & Fisher, 2006). Specific vulnerabilities refer to how our experiences lead us to focus and channel our anxiety (Suárez et al., 2009). If we learned that physical illness is dangerous, maybe through witnessing our family’s reaction whenever anyone got sick, we may focus our anxiety on physical sensations. If we learned that disapproval from others has negative, even dangerous consequences, such as being yelled at or severely punished for even the slightest offense, we might focus our anxiety on social evaluation. If we learn to expect a seemingly inevitable event, we may focus our anxiety on worries about the future. None of these vulnerabilities directly causes anxiety disorders on its own — instead, when all of these vulnerabilities are present, and we experience some triggering life stress, an anxiety disorder may be the result (Barlow, 2002; Suárez et al., 2009). We will briefly explore each of the major anxiety-based disorders, found in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, known as the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Generalized anxiety disorder

Consider the following in which Chase, posting in an online forum, describes her feelings of a persistent and exaggerated sense of anxiety, even when there is little or nothing in her life to provoke it:

For a few months now I’ve had a really bad feeling inside of me. The best way to describe it is like a really bad feeling of negative inevitability, like something really bad is impending, but I don’t know what. It’s like I’m on trial for murder or I’m just waiting to be sent down for something. I have it all of the time but it gets worse in waves that come from nowhere with no apparent triggers. I used to get it before going out for nights out with friends, and it kinda stopped me from doing it as I’d rather not go out and stress about the feeling, but now I have it all the time so it doesn’t really make a difference anymore. (Chase, 2010, “Anxiety?” para. 1)

Chase is probably suffering from a generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), a psychological disorder diagnosed in situations in which a person has been excessively worrying about money, health, work, family life, or relationships for at least six months, even though they know that the concerns are exaggerated. In addition to their feelings of anxiety, people who suffer from GAD may also experience a variety of physical symptoms, including irritability, sleep troubles, difficulty concentrating, muscle aches, trembling, perspiration, and hot flashes. The sufferer cannot deal with what is causing the anxiety, nor avoid it, because there is no clear cause for anxiety. In fact, the sufferer frequently knows, at least cognitively, that there is really nothing to worry about. Nevertheless, the anxiety causes significant distress and dysfunction.

The DSM-5 criteria specify that at least six months of excessive anxiety and worry of this type must be ongoing, happening more days than not for a good proportion of the day, to receive a diagnosis of GAD. About 5.7% of the population has met criteria for GAD at some point during their lifetime (Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Merikangas, & Walters, 2005), making it one of the most common anxiety disorders. Refer to the table below.

| Disorder | 1-Year Prevalence Rates1 | Lifetime Prevalence Rates2 | Prevalence by Gender | Median Age of Onset |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 3.1% | 5.7% | 67% female | 31 years old |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 1.0% | 1.6% | 55% female | 19 years old |

| Panic disorder | 2.7% | 4.7% | 67% female | 24 years old |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 3.5% | 6.8% | 52% female3 | 23 years old |

| Social anxiety | 6.8% | 12.1% | 50% female | 13 years old |

| Specific phobia | 8.7% | 12.5% | 60%–90% female4 | 7–9 years old |

| Data source: [1] Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005; [2] Kessler, Chiu, et al., 2005; [3] Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, and Nelson, 1995; [4] Craske et al., 1996. | ||||

What makes a person with GAD worry more than the average person? Research shows that individuals with GAD are more sensitive and vigilant toward possible threats than people who are not anxious (Aikins & Craske, 2001; Barlow, 2002; Bradley, Mogg, White, Groom, & de Bono, 1999). This may be related to early stressful experiences, which can lead to a view of the world as an unpredictable, uncontrollable, and even dangerous place. Some have suggested that people with GAD worry as a way to gain some control over these otherwise uncontrollable or unpredictable experiences and against uncertain outcomes (Dugas, Gagnon, Ladouceur, & Freeston, 1998). By repeatedly going through all of the possible “what if” scenarios in their mind, the person might feel like they are less vulnerable to an unexpected outcome, giving them the sense that they have some control over the situation (Wells, 2002). Others have suggested people with GAD worry as a way to avoid feeling distressed (Borkovec, Alcaine, & Behar, 2004). For example, Thomas Borkovec and Senqi Hu (1990) found that those who worried when confronted with a stressful situation had less physiological arousal than those who did not worry, maybe because the worry “distracted” them in some way.

The problem is, all of this “what if”-ing doesn’t get the person any closer to a solution or an answer and, in fact, might take them away from important things they should be paying attention to in the moment, such as finishing an important project. Many of the catastrophic outcomes people with GAD worry about are very unlikely to happen, so when the catastrophic event does not materialize, the act of worrying becomes a reinforced response (Borkovec, Hazlett-Stevens, & Diaz, 1999). For example, if a mother spends all night worrying about whether her teenage daughter will get home safe from a night out and the daughter returns home without incident, the mother could easily attribute her daughter’s safe return to her successful “vigil.” What the mother hasn’t learned is that her daughter would have returned home just as safe if she had been focusing on the movie she was watching with her husband, rather than being preoccupied with worries. In this way, the cycle of worry is perpetuated, and subsequently, people with GAD often miss out on many otherwise enjoyable events in their lives.

Panic disorder

Consider the following in which Ceejay, posting in a personal blog, describes feeling a sudden sense of panic:

When I was about 30 I had my first panic attack. I was driving home, my three little girls were in their car seats in the back, and all of a sudden I couldn’t breathe, I broke out into a sweat, and my heart began racing and literally beating against my ribs! I thought I was going to die. I pulled off the road and put my head on the wheel. I remember songs playing on the CD for about 15 minutes and my kids’ voices singing along. I was sure I’d never see them again. And then, it passed. I slowly got back on the road and drove home. I had no idea what it was. (Ceejay, 2006, “My Dance With Panic,” para. 2)

Ceejay is experiencing panic disorder, a psychological disorder characterized by sudden attacks of anxiety and terror that have led to significant behavioural changes in the person’s life. Ceejay’s alarm reaction is called the fight-or-flight response (Cannon, 1929), which is the body’s natural reaction to fear, preparing you to either fight or escape in response to threat or danger. Yet, if this alarm reaction comes “out of the blue,” for no apparent reason, or in a situation in which you didn’t expect to be anxious or fearful, this is called an unexpected panic attack or a false alarm. Because there is no apparent reason or cue for the alarm reaction, you might react to the sensations with intense fear, maybe thinking you are having a heart attack, going crazy, or even dying. You might begin to associate the physical sensations you felt during this attack with this fear and may start to go out of your way to avoid having those sensations again. Symptoms of a panic attack include shortness of breath, heart palpitations, trembling, dizziness, choking sensations, nausea, and an intense feeling of dread or impending doom. Panic attacks can often be mistaken for serious physical illnesses, and they may lead the person experiencing them to go to a hospital emergency room. Panic attacks may last as little as one or as much as 20 minutes, but they often peak and subside within about 10 minutes.

Sufferers are often anxious because they fear that they will have another attack. They focus their attention on the thoughts and images of their fears, becoming excessively sensitive to cues that signal the possibility of threat (MacLeod, Rutherford, Campbell, Ebsworthy, & Holker, 2002). They may also become unsure of the source of their arousal, misattributing it to situations that are not actually the cause. People with panic disorder tend to interpret even normal physical sensations in a catastrophic way, which triggers more anxiety and, ironically, more physical sensations, creating a vicious cycle of panic (Clark, 1986, 1996). The person may begin to avoid a number of situations or activities that produce the same physiological arousal that was present during the beginnings of a panic attack. For example, someone who experienced a racing heart during a panic attack might avoid exercise or caffeine, whereas someone who experienced choking sensations might avoid wearing high-necked sweaters or necklaces. Avoidance of these internal bodily or somatic cues for panic has been termed interoceptive avoidance (Barlow & Craske, 2007; Brown, White, & Barlow, 2005; Craske & Barlow, 2008; Shear et al., 1997).

The individual may also have experienced an overwhelming urge to escape during the unexpected panic attack. This can lead to a sense that certain places or situations — particularly situations where escape might not be possible — are not “safe.” These situations become external cues for panic. If the person begins to avoid several places or situations, or still endures these situations but does so with a significant amount of apprehension and anxiety, then the person also has agoraphobia (Barlow, 2002; Craske & Barlow, 1988, 2008). People who suffer from agoraphobia may have great difficulty leaving their homes and interacting with other people. As such, agoraphobia can cause significant disruption to a person’s life, such as adding hours to a commute to avoid taking the train or only ordering take-out to avoid having to enter a grocery store. In one tragic example, a woman suffering from agoraphobia had not left her apartment for 20 years and had spent the past 10 years confined to one small area of her apartment, away from the view of the outside. In some cases, agoraphobia develops in the absence of panic attacks and, therefore, is a separate disorder in DSM-5. However, agoraphobia often accompanies panic disorder.

About 4.7% of the population has met criteria for panic disorder or agoraphobia over their lifetime (Kessler, Chiu, et al., 2005; Kessler et al., 2006). In all of these cases of panic disorder, what was once an adaptive natural alarm reaction now becomes a learned, and much feared, false alarm.

Specific phobias

A phobia — from the Greek word phobos, which means fear — is a specific fear of a certain object, situation, or activity. The fear experience can range from a sense of unease to a full-blown panic attack. Most people learn to live with their phobias, but for others, the fear can be so debilitating that they go to extremes to avoid the fearful situation. A sufferer of arachnophobia (i.e., fear of spiders), for example, may refuse to enter a room until it has been checked thoroughly for spiders, or may refuse to vacation in the countryside because spiders may be there. Phobias are characterized by their specificity and their irrationality. A person with acrophobia (i.e., fear of heights) could fearlessly sail around the world on a sailboat with no concerns, yet they might refuse to go out onto the balcony on the fifth floor of a building.

The list of possible phobias is staggering, but four major subtypes of specific phobia are recognized: blood-injury-injection (BII) type, situational type (e.g., planes, elevators, or enclosed places), natural environment type for events one may encounter in nature (e.g., heights, storms, and water), and animal type.

A fifth subtype — labelled “other” — includes phobias that do not fit any of the four major subtypes (e.g., fears of choking, vomiting, or contracting an illness). Most phobic reactions cause a surge of activity in the sympathetic nervous system and increased heart rate and blood pressure, maybe even a panic attack. However, people with BII type phobias usually experience a marked drop in heart rate and blood pressure and may even faint. In this way, those with BII phobias almost always differ in their physiological reaction from people with other types of phobia (Barlow & Liebowitz, 1995; Craske, Antony, & Barlow, 2006; Hofmann, Alpers, & Pauli, 2009; Ost, 1992). BII phobia also runs in families more strongly than any phobic disorder known (Antony & Barlow, 2002; Page & Martin, 1998). Specific phobia is one of the most common psychological disorders, with 12.5% of the U.S. population reporting a lifetime history of fears significant enough to be considered a phobia (Arrindell et al., 2003; Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005). Most people who suffer from specific phobia tend to have multiple phobias of several types (Hofmann, Lehman, & Barlow, 1997). Interestingly, phobias are about twice as prevalent in women as in men (Fredrikson, Annas, Fischer, & Wik, 1996; Kessler, Meron-Ruscio, Shear, & Wittchen, 2009).

Social anxiety disorder

Many people consider themselves shy, and most people find social evaluation uncomfortable at best, or giving a speech somewhat mortifying. Yet, only a small proportion of the population fear these types of situations significantly enough to merit a diagnosis of social anxiety disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is more than exaggerated shyness (Bogels et al., 2010; Schneier et al., 1996). To receive a diagnosis of SAD, the fear and anxiety associated with social situations must be so strong that the person avoids them entirely, or if avoidance is not possible, the person endures them with a great deal of distress. Further, the fear and avoidance of social situations must get in the way of the person’s daily life, or seriously limit their academic or occupational functioning. For example, a student may compromise their perfect grade point average because they could not complete a required oral presentation in one of their classes, causing them to fail the course. Fears of negative evaluation might make someone repeatedly turn down invitations to social events or avoid having conversations with people, leading to greater and greater isolation.

The specific social situations that trigger anxiety and fear range from one-on-one interactions (e.g., starting or maintaining a conversation), to performance-based situations (e.g., giving a speech or performing on stage), or to assertiveness (e.g., asking someone to change disruptive or undesirable behaviours). Fear of social evaluation might even extend to such things as using public restrooms, eating in a restaurant, filling out forms in a public place, or even reading on a train. Any type of situation that could potentially draw attention to the person can become a feared social situation (e.g., someone avoiding situations in which they might have to use a public restroom for fear that someone would hear them in the bathroom stall and think they were disgusting). If the fear is limited to performance-based situations, such as public speaking, a diagnosis of SAD performance only is assigned.

What causes someone to fear social situations to such a large extent? The person may have learned growing up that social evaluation in particular can be dangerous, creating a specific psychological vulnerability to develop social anxiety (Bruch & Heimberg, 1994; Lieb et al., 2000; Rapee & Melville, 1997). For example, the person’s caregivers may have harshly criticized and punished them for even the smallest mistake, maybe even punishing them physically.

Alternatively, someone might have experienced a social trauma that had lasting effects, such as being bullied or humiliated. Interestingly, one group of researchers found that 92% of adults in their study sample with social phobia experienced severe teasing and bullying in childhood, compared with only 35% to 50% among people with other anxiety disorders (McCabe, Antony, Summerfeldt, Liss, & Swinson, 2003). Someone else might react so strongly to the anxiety provoked by a social situation that they have an unexpected panic attack. This panic attack then becomes associated with the social situation, becoming a conditioned response and causing the person to fear they will panic the next time they are in that situation. This is not considered panic disorder, however, because the person’s fear is more focused on social evaluation than having unexpected panic attacks, and the fear of having an attack is limited to social situations. As many as 12.1% of the general population suffer from social phobia at some point in their lives (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005), making it one of the most common anxiety disorders, second only to specific phobia.

Obsessive-compulsive disorders

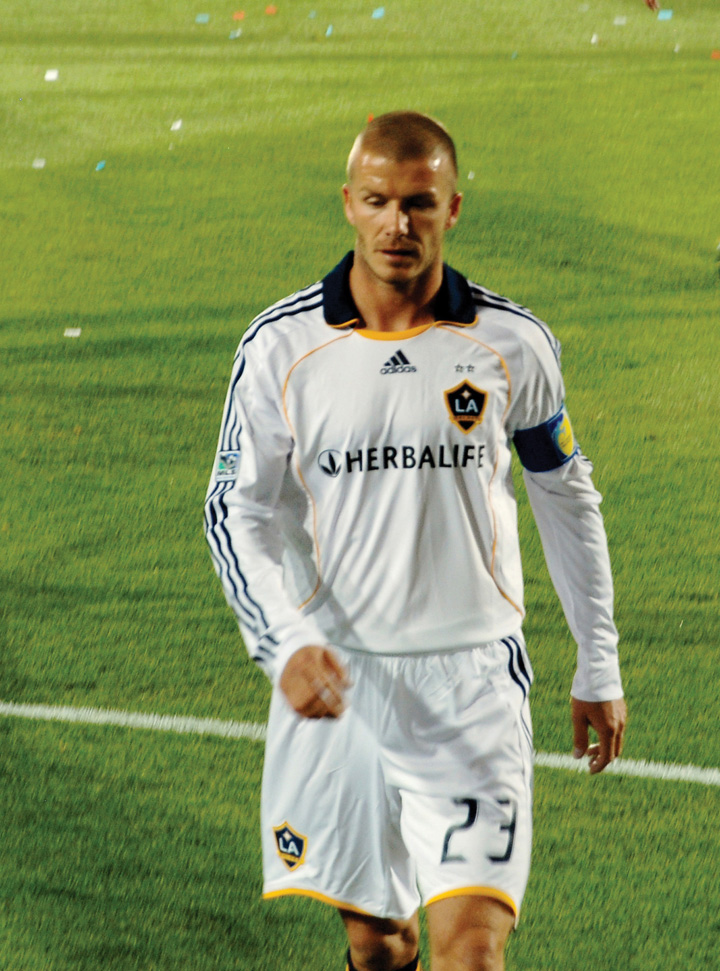

Although he is best known his perfect shots on the field, the British soccer star David Beckham (see Figure 15.7) also suffers from obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). As he describes it:

I have got this obsessive-compulsive disorder where I have to have everything in a straight line or everything has to be in pairs. I’ll put my Pepsi cans in the fridge, and if there’s one too many, then I’ll put it in another cupboard somewhere. I’ve got that problem. I’ll go into a hotel room. Before I can relax, I have to move all the leaflets and all the books and put them in a drawer. Everything has to be perfect. (Dolan, 2006, para. 7)

David Beckham’s experience with obsessive behaviour is not unusual. We all get a little obsessive at times. We may continuously replay a favorite song in our heads, worry about getting the right outfit for an upcoming party, or find ourselves analyzing a series of numbers that seem to have a certain pattern. Our everyday compulsions can be useful. Going back inside the house once more to be sure that we really did turn off the sink faucet or checking the mirror a couple of times to be sure that our hair is combed are not necessarily bad ideas.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a psychological disorder that is diagnosed when an individual continuously experiences distressing or frightening thoughts, and engages in obsessions (e.g., repetitive thoughts) or compulsions (e.g., repetitive behaviours) in an attempt to calm these thoughts. OCD is diagnosed when the obsessive thoughts are so disturbing and the compulsive behaviours are so time consuming that they cause distress and significant dysfunction in a person’s everyday life. Washing your hands once or even twice to make sure that they are clean is normal; washing them 20 times is not. Keeping your fridge neat is a good idea; spending hours a day on it is not. The sufferers know that these rituals are senseless, but they cannot bring themselves to stop them, in part because the relief that they feel after they perform them acts as a reinforcer, making the behaviour more likely to occur again.

Their strange or unusual thoughts are taken to mean something much more important and real, maybe even something dangerous or frightening. The urge to engage in some behaviour, such as straightening a picture, can become so intense that it is nearly impossible not to carry it out, or causes significant anxiety if it can’t be carried out. Further, someone with OCD might become preoccupied with the possibility that the behaviour wasn’t carried out to completion and feel compelled to repeat the behaviour again and again, maybe several times before they are satisfied.

To receive a diagnosis of OCD, a person must experience obsessive thoughts and compulsions that seem irrational or nonsensical, but that keep coming into their mind. Some examples of obsessions include doubting thoughts (e.g., doubting a door is locked or an appliance is turned off), thoughts of contamination (e.g., thinking that touching almost anything might give you cancer), or aggressive thoughts or images that are unprovoked or nonsensical. Compulsions may be carried out in an attempt to neutralize some of these thoughts, providing temporary relief from the anxiety the obsessions cause, or they may be nonsensical in and of themselves. Either way, compulsions are distinct in that they must be repetitive or excessive, the person feels “driven” to carry out the behaviour, and the person feels a great deal of distress if they can’t engage in the behaviour. Some examples of compulsive behaviours are repetitive washing in response to contamination obsessions, repetitive checking of locks, door handles, and appliances in response to doubting obsessions, ordering and arranging things to ensure symmetry, or doing things according to a specific ritual or sequence, such as getting dressed or ready for bed in a specific order. To meet diagnostic criteria for OCD, engaging in obsessions and compulsions must take up a significant amount of the person’s time, at least an hour per day, and must cause significant distress or impairment in functioning. About 1.6% of the population has met criteria for OCD over the course of a lifetime (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005). Whereas OCD was previously categorized as an anxiety disorder, in the DSM-5 it has been reclassified under the more specific category of “obsessive-compulsive and related disorders” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

People with OCD often confuse having an intrusive thought with their potential for carrying out the thought. For most people, when they have a strange or frightening thought, they are able to let it go; however, a person with OCD may become “stuck” on the thought and be intensely afraid that they might somehow lose control and act on it, or worse, they believe that having the thought is just as bad as doing it. This is called thought-action fusion. For example, one known patient was plagued by thoughts that she would cause harm to her young daughter. She experienced intrusive images of throwing hot coffee in her daughter’s face or pushing her face underwater when she was giving her a bath. These images were so terrifying to the patient that she would no longer allow herself any physical contact with her daughter and would leave her daughter in the care of a babysitter if her husband or another family was not available to supervise her. In reality, the last thing she wanted to do was harm her daughter, and she had no intention or desire to act on the aggressive thoughts and images, but these thoughts were so horrifying to her that she made every attempt to prevent herself from the potential of carrying them out, even if it meant not being able to hold, cradle, or cuddle her daughter. These are the types of struggles people with OCD face every day.

Sufferers of OCD may avoid certain places that trigger the obsessive thoughts or use alcohol or drugs to try to calm themselves down. OCD has a low prevalence rate, affecting around 1% of the population in a given year, in relation to other anxiety disorders, and it usually develops in adolescence or early adulthood (Horwath & Weissman, 2000; Samuels & Nestadt, 1997). The course of OCD varies from person to person. Symptoms can come and go, decrease, or worsen over time.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

People who have survived a terrible ordeal — such as combat, torture, sexual assault, imprisonment, abuse, natural disasters, or the death of someone close to them — may develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The anxiety may begin months or even years after the event. While many people face traumatic events, not everyone who faces a trauma develops a disorder. Some, with the help of family and friends, are able to recover and continue on with their lives (Friedman, 2009). For some, however, the months and years following a trauma are filled with intrusive reminders of the event, a sense of intense fear that another traumatic event might occur, or a sense of isolation and emotional numbing. They may engage in a host of behaviours intended to protect themselves from being vulnerable or unsafe, such as constantly scanning their surroundings to look for signs of potential danger, never sitting with their back to the door, or never allowing themselves to be anywhere alone. This lasting reaction to trauma is what characterizes PTSD.

A diagnosis of PTSD begins with the traumatic event itself. An individual must have been exposed to an event that involves actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence. To receive a diagnosis of PTSD, exposure to the event must include either directly experiencing the event, witnessing the event happening to someone else, learning that the event occurred to a close relative or friend, or having repeated or extreme exposure to details of the event, such as in the case of first responders. The person subsequently re-experiences the event through both intrusive memories and nightmares. Some memories may come back so vividly that the person feels like they are experiencing the event all over again, what is known as having a flashback. The individual may avoid anything that reminds them of the trauma, including conversations, places, or even specific types of people. They may feel emotionally numb or restricted in their ability to feel, which may interfere in their interpersonal relationships. The person may not be able to remember certain aspects of what happened during the event. They may feel a sense of a foreshortened future, that they will never marry, have a family, or live a long, full life. They may be jumpy or easily startled, hypervigilant to their surroundings, or quick to anger. The symptoms may be felt especially when approaching the area where the event took place or when the anniversary of that event is near.

The prevalence of PTSD among the population as a whole is relatively low, with 6.8% having experienced PTSD at some point in their life (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005). Combat and sexual assault are the most common precipitating traumas (Kessler et al., 1995). Whereas PTSD was previously categorized as an anxiety disorder, in the DSM-5, it has been reclassified under the more specific category of “trauma- and stressor-related disorders” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

A person with PTSD is particularly sensitive to both internal and external cues that serve as reminders of their traumatic experience. The physical sensations of arousal present during the initial trauma can become threatening in and of themselves, becoming a powerful reminder of the event. Someone might avoid watching intense or emotional movies in order to prevent the experience of emotional arousal. Avoidance of conversations, reminders, or even of the experience of emotion itself may also be an attempt to avoid triggering internal cues. External stimuli that were present during the trauma can also become strong triggers. For example, if a woman is raped by a man wearing a red t-shirt, she may develop a strong alarm reaction to the sight of red shirts, or perhaps even more indiscriminately to anything with a similar color red. A combat veteran who experienced a strong smell of gasoline during a roadside bomb attack may have an intense alarm reaction when pumping gas back at home. Individuals with a psychological vulnerability toward viewing the world as uncontrollable and unpredictable may particularly struggle with the possibility of additional future, unpredictable traumatic events, fueling their need for hypervigilance and avoidance, and perpetuating the symptoms of PTSD.

PTSD has affected approximately 8% of the population (Kessler, Berglund, et al., 2005). PTSD is a frequent outcome of childhood or adult sexualabuse. Women are more likely to develop PTSD than men (Davidson, 2000).

Romeo Dallaire (see Figure 15.9), who served as Canadian Lieutenant General and Force Commander of the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), the ill-fated United Nations peacekeeping force for Rwanda in 1993 and 1994, attempted to stop the genocide that was being waged by Hutu extremists against Tutsis and Hutu moderates. Dallaire has worked to bring understanding of post-traumatic stress disorder to the general public. He was a visiting lecturer at several Canadian and American universities and a Fellow of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy, Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. He has also pursued research on conflict resolution and the use of child soldiers and written several articles and chapters in publications on conflict resolution, humanitarian assistance, and human rights. In 2010, he wrote a book about the use of child soldiers: They Fight Like Soldiers, They Die Like Children.

Risk factors for PTSD include the degree of the trauma’s severity, the lack of family and community support, and additional life stressors (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000). Many people with PTSD also suffer from another mental disorder, particularly depression, other anxiety disorders, and substance abuse (Brady, Back, & Coffey, 2004).

Explaining anxiety disorders

Both nature and nurture contribute to the development of anxiety disorders. In terms of our evolutionary experiences, humans have evolved to fear dangerous situations. Those of us who had a healthy fear of the dark, of storms, of high places, of closed spaces, and of spiders and snakes were more likely to survive and have descendants. Our evolutionary experience can account for some modern fears as well. A fear of elevators may be a modern version of our fear of closed spaces, while a fear of flying may be related to a fear of heights.

Also supporting the role of biology, anxiety disorders, including PTSD, are heritable (Hettema, Neale, & Kendler, 2001), and molecular genetics studies have found a variety of genes that are important in the expression of such disorders (Smoller et al., 2008; Thoeringer et al., 2009). Neuroimaging studies have found that anxiety disorders are linked to areas of the brain that are associated with emotion, blood pressure and heart rate, decision making, and action monitoring (Brown & McNiff, 2009; Damsa, Kosel, & Moussally, 2009). People who experience PTSD also have a somewhat smaller hippocampus in comparison with those who do not, and this difference leads them to have a very strong sensitivity to traumatic events (Gilbertson et al., 2002).

Whether the genetic predisposition to anxiety becomes expressed as a disorder depends on environmental factors. People who were abused in childhood are more likely to be anxious than those who had non-abusive childhoods, even with the same genetic disposition to anxiety sensitivity (Stein, Schork, & Gelernter, 2008). Additionally, the most severe anxiety and dissociative disorders, such as PTSD, are usually triggered by the experience of a major stressful event. One problem is that modern life creates a lot of anxiety. Although our life expectancy and quality of life have improved over the past 50 years, the same period has also created a sharp increase in anxiety levels (Twenge, 2006). These changes suggest that most anxiety disorders stem from perceived, rather than actual, threats to our wellbeing.

Anxieties are also learned through classical and operant conditioning. Just as rats that are shocked in their cages develop a chronic anxiety toward their laboratory environment, which has become a conditioned stimulus for fear, rape victims may feel anxiety when passing by the scene of the crime, and victims of PTSD may react to memories or reminders of the stressful event. Classical conditioning may also be accompanied by stimulus generalization. A single dog bite can lead to generalized fear of all dogs; a panic attack that follows an embarrassing moment in one place may be generalized to a fear of all public places. People’s responses to their anxieties are often reinforced. Behaviours become compulsive because they provide relief from the torment of anxious thoughts. Similarly, leaving or avoiding fear-inducing stimuli leads to feelings of calmness or relief, which reinforces phobic behaviour.

Source: Adapted from Barlow and Ellard (2020).

Key Takeaways

- Anxiety is a natural part of life, but too much anxiety can be debilitating. Every year millions of people suffer from anxiety disorders.

- People who suffer from generalized anxiety disorder experience anxiety, as well as a variety of physical symptoms.

- Panic disorder involves the experience of panic attacks, including shortness of breath, heart palpitations, trembling, and dizziness.

- Phobias are specific fears of a certain object, situation, or activity. Phobias are characterized by their specificity and their irrationality.

- A common phobia is social phobia, which is extreme shyness around people or discomfort in social situations.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder is diagnosed when a person’s repetitive thoughts are so disturbing and their compulsive behaviours so time consuming that they cause distress and significant disruption in a person’s everyday life.

- People who have survived a terrible ordeal — such as combat, torture, rape, imprisonment, abuse, natural disasters, or the death of someone close to them — may develop PTSD.

- Both nature and nurture contribute to the development of anxiety disorders.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Under what situations do you experience anxiety? Are these experiences rational or irrational? Does the anxiety keep you from doing some things that you would like to be able to do?

- Do you or people you know suffer from phobias? If so, what are the phobias, and how do you think the phobias began? Do they seem more genetic or more environmental in origin?

Image Attributions

Figure 15.6. School Bully by ihtatho is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 license.

Figure 15.7. Beckham LA Galaxy by Rajeev Patel is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 15.8. Yes, You May Have an Obsession or Two by benjamin sTone is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 15.9. RoméoDallaire07TIFF by Gordon Correll is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

References

Aikins, D. E., & Craske, M. G. (2001). Cognitive theories of generalized anxiety disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 24(1), 57–74, vi.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Antony, M. M., & Barlow, D. H. (2002). Specific phobias. In D. H. Barlow (Ed.), Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Arrindell, W. A., Eisemann, M., Richter, J., Oei, T. P., Caballo, V. E., van der Ende, J., . . . Zaldívar, F. (2003). Phobic anxiety in 11 nations. Part I: Dimensional constancy of the five-factor model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(4), 461–479.

Barlow, D. H. (2002). Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Barlow, D. H., & Craske, M. G. (2007). Mastery of your anxiety and panic (4th ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Barlow, D. H., & Ellard, K. K. (2020). Anxiety and related disorders. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds.), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF. Retrieved from http://noba.to/xms3nq2c

Barlow, D. H., & Liebowitz, M. R. (1995). Specific and social phobias. In H. I. Kaplan & B. J. Sadock (Eds.), Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry: VI (pp. 1204–1217). Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins.

Bogels, S. M., Alden, L., Beidel, D. C., Clark, L. A., Pine, D. S., Stein, M. B., & Voncken, M. (2010). Social anxiety disorder: Questions and answers for the DSM-V. Depression and Anxiety, 27(2), 168–189.

Borkovec, T. D., Alcaine, O. M., & Behar, E. (2004). Avoidance theory of worry and generalized anxiety disorder. In R. G. Heimberg, C. L. Turk, & D. S. Mennin (Eds.), Generalized anxiety disorder: Advances in research and practice (pp. 77–108). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Borkovec, T. D., Hazlett-Stevens, H., & Diaz, M. L. (1999). The role of positive beliefs about worry in generalized anxiety disorder and its treatment. Clinical Psychology and Pscyhotherapy, 6, 69–73.

Borkovec, T. D., & Hu, S. (1990). The effect of worry on cardiovascular response to phobic imagery. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28(1), 69–73.

Bradley, B. P., Mogg, K., White, J., Groom, C., & de Bono, J. (1999). Attentional bias for emotional faces in generalized anxiety disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38(3), 267–278.

Brady, K. T., Back, S. E., & Coffey, S. F. (2004). Substance abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(5), 206–209.

Brewin, C., Andrews, B., & Valentine, J. (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 748–766.

Brown, T. A., & McNiff, J. (2009). Specificity of autonomic arousal to DSM-IV panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(6), 487–493.

Brown, T. A., White, K. S., & Barlow, D. H. (2005). A psychometric reanalysis of the Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43, 337–355.

Bruch, M. A., & Heimberg, R. G. (1994). Differences in perceptions of parental and personal characteristics between generalized and non-generalized social phobics. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 8, 155–168.

Cannon, W. B. (1929). Bodily changes in pain, hunger, fear and rage. Oxford, England: Appleton.

Ceejay. (2006, September). My dance with panic [Web log post]. Panic Survivor. Retrieved from http://www.panicsurvivor.com/index.php/2007102366/Survivor-Stories/My-Dance-With-Panic.html

Chase. (2010). Re: “anxiety?” [Online forum comment]. Mental Health Forum. Retrieved from http://www.mentalhealthforum.net/forum/showthread.php?t=9359

Chorpita, B. F., & Barlow, D. H. (1998). The development of anxiety: the role of control in the early environment. Psychological Bulletin, 124(1), 3–21.

Clark, D. M. (1986). A cognitive approach to panic. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 24(4), 461–470.

Clark, D. M. (1996). Panic disorder: From theory to therapy. In P. Salkovskis (Ed.), Fronteirs of cognitive therapy (pp. 318–344). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Craske, M. G., Antony, M. M., & Barlow, D. H. (2006). Mastering your fears and phobias: Therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Craske, M. G., & Barlow, D. H. (1988). A review of the relationship between panic and avoidance. Clinical Psychology Review, 8, 667–685.

Craske, M. G., & Barlow, D. H. (2008). Panic disorder and agoraphobia. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Craske, M. G., Barlow, D. H., Clark, D. M., Curtis, G. C., Hill, E. M., Himle, J. A., . . . Warwick, H. M. C. (1996). Specific (simple) phobia. In T. A. Widiger, A. J. Frances, H. A. Pincus, R. Ross, M. B. First, & W. W. Davis (Eds.), DSM-IV sourcebook (Vol. 2, pp. 473–506). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Damsa, C., Kosel, M., & Moussally, J. (2009). Current status of brain imaging in anxiety disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 22(1), 96–110.

Davidson, J. (2000). Trauma: The impact of post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 14(2 Suppl 1), S5–S12.

Dolan, A. (2006, April 3). The obsessive disorder that haunts my life. Daily Mail. Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-381802/The-obsessive-disorder-haunts-life.html

Drabant, E. M., Ramel, W., Edge, M. D., Hyde, L. W., Kuo, J. R., Goldin, P. R., . . . Gross, J. J. (2012). Neural mechanisms underlying 5-HTTLPR-related sensitivity to acute stress. American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(4), 397–405.

Dugas, M. J., Gagnon, F., Ladouceur, R., & Freeston, M. H. (1998). Generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary test of a conceptual model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(2), 215–226.

Fredrikson, M., Annas, P., Fischer, H., & Wik, G. (1996). Gender and age differences in the prevalence of specific fears and phobias. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34(1), 33–39.

Friedman, M. J. (2009). Phenomenology of postraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. In M. M. Antony & M. B. Stein (Eds.), Oxford handbook of anxiety and related disorders (pp. 65–72). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Gelernter, J., & Stein, M. B. (2009). Heritability and genetics of anxiety disorders. In M. M. Antony & M. B. Stein (Eds.), Oxford handbook of anxiety and related disorders (pp. 87–96). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Gilbertson, M. W., Shenton, M. E., Ciszewski, A., Kasai, K., Lasko, N. B., Orr, S. P., . . . Pitman, R. K. (2002). Smaller hippocampal volume predicts pathologic vulnerability to psychological trauma. Nature Neuroscience, 5(11), 1242–1247.

Gunnar, M. R., & Fisher, P. A. (2006). Bringing basic research on early experience and stress neurobiology to bear on preventive interventions for neglected and maltreated children. Developmental Psychopathology, 18(3), 651–677.

Hettema, J. M., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (2001). A review and meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(10), 1568–1578.

Hofmann, S. G., Alpers, G. W., & Pauli, P. (2009). Phenomenology of panic and phobic disorders. In M. M. Antony & M. B. Stein (Eds.), Oxford handbook of anxiety and related disorders (pp. 34–46). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Hofmann, S. G., Lehman, C. L., & Barlow, D. H. (1997). How specific are specific phobias? Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 28(3), 233–240.

Horwath, E., & Weissman, M. (2000). The epidemiology and cross-national presentation of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(3), 493–507.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602.

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617–627.

Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Jin, R., Ruscio, A. M., Shear, K., & Walters, E. E. (2006). The epidemiology of panic attacks, panic disorder, and agoraphobia in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(4), 415–424.

Kessler, R. C., Meron-Ruscio, A., Shear, K., & Wittchen, H. (2009). Epidemiology of anxiety disorders. In M. M. Antony & M. B. Stein (Eds.), Oxford handbook of anxiety and related disorders (pp. 19–33). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Kessler, R. C., Sonnega, A., Bromet, E., Hughes, M., & Nelson, C. B. (1995). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52(12), 1048–1060.

Lieb, R., Wittchen, H. U., Hofler, M., Fuetsch, M., Stein, M. B., & Merikangas, K. R. (2000). Parental psychopathology, parenting styles, and the risk of social phobia in offspring: A prospective-longitudinal community study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(9), 859–866.

MacLeod, C., Rutherford, E., Campbell, L., Ebsworthy, G., & Holker, L. (2002). Selective attention and emotional vulnerability: Assessing the causal basis of their association through the experimental manipulation of attentional bias. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111(1), 107–123.

McCabe, R. E., Antony, M. M., Summerfeldt, L. J., Liss, A., & Swinson, R. P. (2003). Preliminary examination of the relationship between anxiety disorders in adults and self-reported history of teasing or bullying experiences. Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 32(4), 187–193.

Ost, L. G. (1992). Blood and injection phobia: Background and cognitive, physiological, and behavioral variables. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 101(1), 68–74.

Page, A. C., & Martin, N. G. (1998). Testing a genetic structure of blood-injury-injection fears. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 81(5), 377–384.

Rapee, R. M., & Melville, L. F. (1997). Recall of family factors in social phobia and panic disorder: Comparison of mother and offspring reports. Depress Anxiety, 5(1), 7–11.

Samuels, J., & Nestadt, G. (1997). Epidemiology and genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder. International Review of Psychiatry, 9, 61–71.

Schneier, F. R., Leibowitz, M. R., Beidel, D. C. J., Fyer A., George, M. S., Heimberg, R. G., . . . Versiani, M. (1996). Social phobia. In T. A. Widiger, A. J. Frances, H. A. Pincus, R. Ross, M. B. First, & W. W. Davis (Eds.), DSM-IV sourcebook (Vol. 2, pp. 507–548). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Shear, M. K., Brown, T. A., Barlow, D. H., Money, R., Sholomskas, D. E., Woods, S. W., . . . Papp, L. A. (1997). Multicenter collaborative panic disorder severity scale. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(11), 1571–1575.

Smoller, J. W., Block, S. R., & Young, M. M. (2009). Genetics of anxiety disorders: The complex road from DSM to DNA. Depression and Anxiety, 26(11), 965–975.

Smoller, J. W., Paulus, M., Fagerness, J., Purcell, S., Yamaki, L., Hirshfeld-Becker, D., . . . Stein, M. (2008). Influence of RGS2 on anxiety-related temperament, personality, and brain function. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(3), 298–308.

Stein, M., Schork, N., & Gelernter, J. (2008). Gene-by-environment (serotonin transporter and childhood maltreatment) interaction for anxiety sensitivity, an intermediate phenotype for anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33(2), 312–319.

Suárez, L, Bennett, S., Goldstein, C., & Barlow, D. H. (2009). Understanding anxiety disorders from a “triple vulnerabilities” framework. In M. M. Antony & M. B. Stein (Eds.), Oxford handbook of anxiety and related disorders (pp. 153–172). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Thoeringer, C., Ripke, S., Unschuld, P., Lucae, S., Ising, M., Bettecken, T., . . . Erhardt, A. (2009). The GABA transporter 1 (SLC6A1): A novel candidate gene for anxiety disorders. Journal of Neural Transmission, 116(6), 649–657.

Twenge, J. (2006). Generation me. New York, NY: Free Press.

Wells, A. (2002). GAD, metacognition, and mindfulness: An information processing analysis. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 9, 95–100.