5.4 Tasting, Smelling, and Touching

Learning Objectives

- Summarize how the senses of taste and olfaction transduce stimuli into perceptions.

- Describe the process of transduction in the senses of touch and proprioception.

- Outline the gate control theory of pain, and explain why pain matters and how it may be controlled.

Although vision and hearing are by far the most important senses, human sensation is rounded out by four others, each of which provides an essential avenue to a better understanding of, and response to, the world around us. These other senses are taste, smell, touch, and proprioception, which is our sense of body position and movement.

Tasting

Taste is important not only because it allows us to enjoy the food we eat, but, even more crucial, because it leads us toward foods that provide energy, such as sugar, and away from foods that could be harmful. Many children are picky eaters for a reason; they are biologically predisposed to be very careful about what they eat. Together with the sense of smell, taste helps us maintain appetite, assess potential dangers like the odour of a gas leak or a burning house, and avoid eating poisonous or spoiled food.

Our ability to taste begins at the taste receptors on the tongue. The tongue detects six different taste sensations, known as sweet, salty, sour, bitter, piquancy (i.e., spicy), and umami (i.e., savoury). Umami is a “meaty” taste associated with meats, cheeses, soy, seaweed, and mushrooms, and it is notably found in monosodium glutamate (MSG), a popular flavour enhancer (Ikeda, 1909/2002; Sugimoto & Ninomiya, 2005).

Our tongues are covered with taste buds, which are designed to sense chemicals in the mouth. Most taste buds are located in the top outer edges of the tongue, but there are also receptors at the back of the tongue as well as on the walls of the mouth and at the back of the throat. As we chew food, it dissolves and enters the taste buds, triggering nerve impulses that are transmitted to the brain (Northcutt, 2004). Human tongues are covered with 2,000 to 10,000 taste buds, and each bud contains between 50 and 100 taste receptor cells. Taste buds are activated very quickly; a salty or sweet taste that touches a taste bud for even one-tenth of a second will trigger a neural impulse (Kelling & Halpern, 1983). On average, taste buds live for about five days, after which new taste buds are created to replace them. As we get older, however, the rate of creation decreases, making us less sensitive to taste. This change helps explain why some foods that seem so unpleasant in childhood are more enjoyable in adulthood.

The area of the sensory cortex that responds to taste is in a very similar location to the area that responds to smell, a fact that helps explain why the sense of smell also contributes to our experience of the things we eat. You may remember having had difficulty tasting food when you had a bad cold, and if you block your nose and taste slices of raw potato, apple, and parsnip, you will not be able to taste the differences between them. Our experience of texture in a food — that is, the way we feel it on our tongues — also influences how we taste it.

Smelling

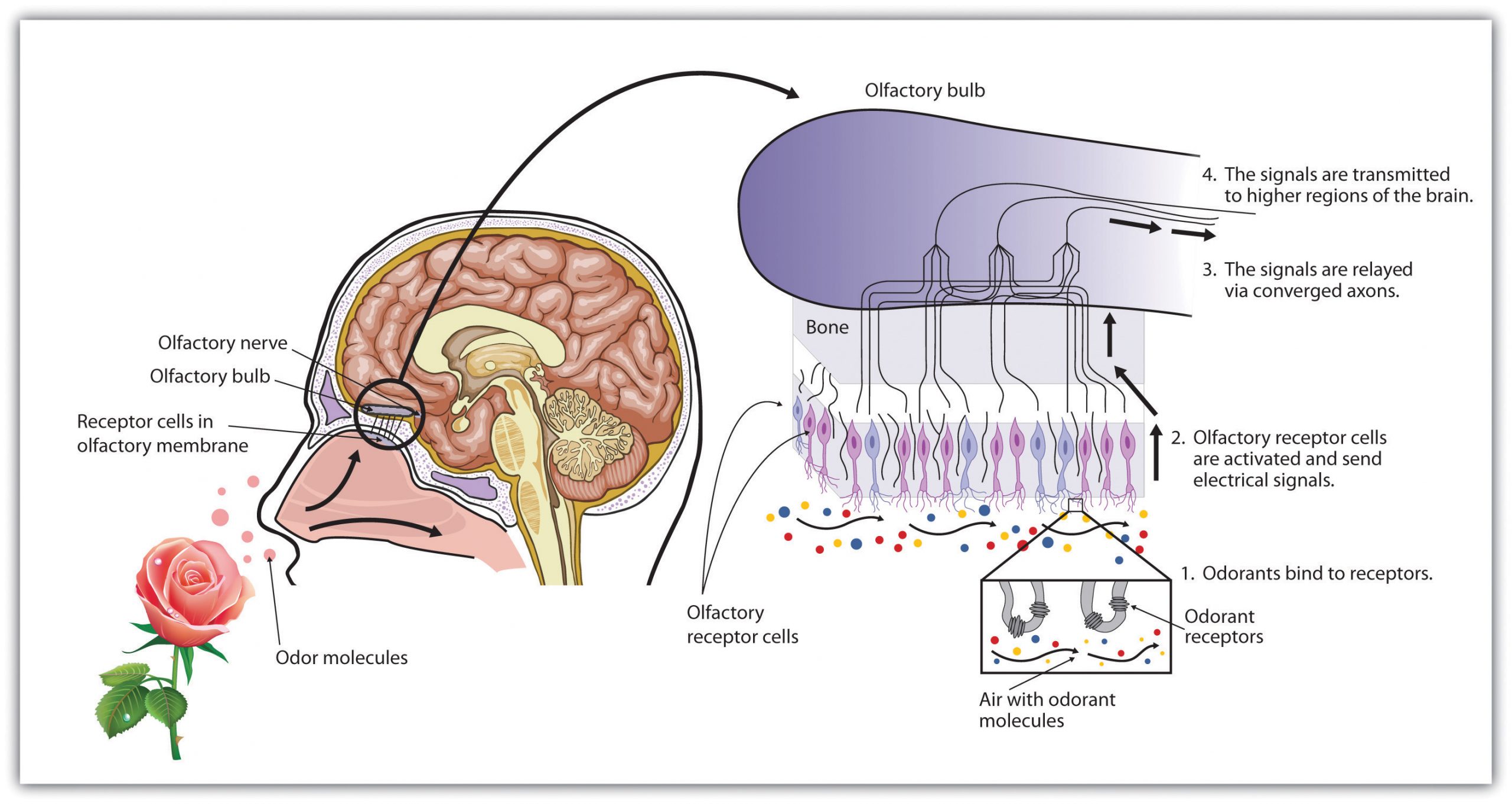

As we breathe in air through our nostrils, we inhale airborne chemical molecules, which are detected by the 10 million to 20 million receptor cells embedded in the olfactory membrane of the upper nasal passage. The olfactory receptor cells are topped with tentacle-like protrusions that contain receptor proteins. When an odour receptor is stimulated (see Figure 5.20), the membrane sends neural messages up the olfactory nerve to the brain.

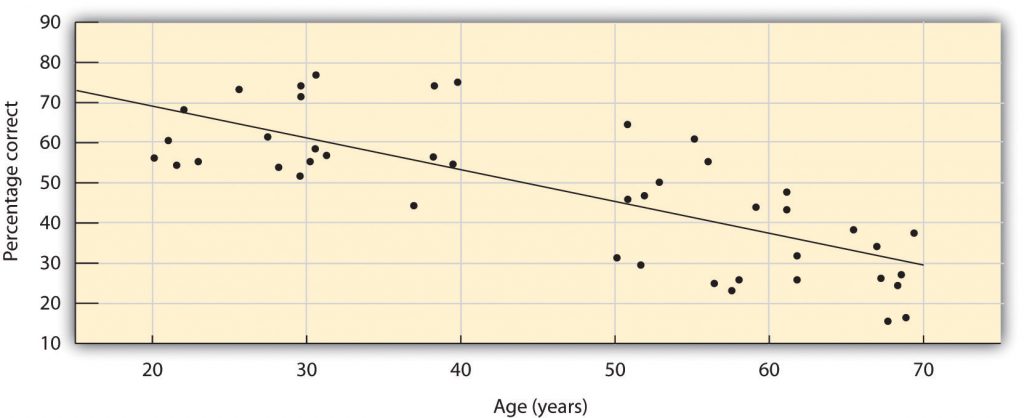

We have approximately 1,000 types of odour receptor cells (Bensafi et al., 2004), and it is estimated that we can detect 10,000 different odours (Malnic, Hirono, Sato, & Buck, 1999). The receptors come in many different shapes and respond selectively to different smells. Like a lock and key, different chemical molecules fit into different receptor cells, and odours are detected according to their influence on a combination of receptor cells. Just as the 10 digits from 0 to 9 can combine in many different ways to produce an endless array of phone numbers, odour molecules bind to different combinations of receptors, and these combinations are decoded in the olfactory cortex. The sense of smell peaks in early adulthood and then begins a slow decline (see Figure 5.21). By ages 60 to 70, the sense of smell has become sharply diminished. In addition, women tend to have a more acute sense of smell than men.

Touching

The sense of touch is essential to human development. Infants thrive when they are cuddled and attended to, but not if they are deprived of human contact (Baysinger, Plubell, & Harlow, 1973; Feldman, 2007; Haradon, Bascom, Dragomir, & Scripcaru, 1994). Touch communicates warmth, caring, and support, and it is an essential part of the enjoyment we gain from our social interactions with close others (Field et al., 1997; Keltner, 2009).

The skin, the largest organ of the body, is the sensory organ for touch. The skin contains a variety of nerve endings, combinations of which respond to particular types of pressures and temperatures. When you touch different parts of the body, you will find that some areas are more ticklish, whereas other areas respond more to pain, cold, or heat.

The thousands of nerve endings in the skin respond to four basic sensations — pressure, hot, cold, and pain — but only the sensation of pressure has its own specialized receptors. Other sensations are created by a combination of the other four. For instance:

- The experience of a tickle is caused by the stimulation of neighbouring pressure receptors.

- The experience of heat is caused by the stimulation of hot and cold receptors.

- The experience of itching is caused by repeated stimulation of pain receptors.

- The experience of wetness is caused by repeated stimulation of cold and pressure receptors.

The skin is important, not only in providing information about touch and temperature, but also in proprioception, which is the ability to sense the position and movement of our body parts. Proprioception is accomplished by specialized neurons located in the skin, joints, bones, ears, and tendons, which send messages about the compression and the contraction of muscles throughout the body. Without this feedback from our bones and muscles, we would be unable to play sports, walk, or even stand upright.

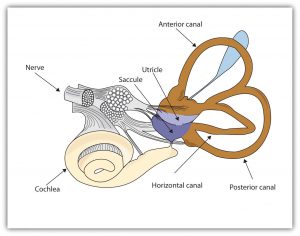

The ability to keep track of where the body is moving is also provided by the vestibular system, which is a set of liquid-filled areas in the inner ear that monitors the head’s position and movement, maintaining the body’s balance. The vestibular system includes the semicircular canals and the vestibular sacs (see Figure 5.22). These sacs connect the canals with the cochlea. The semicircular canals sense the rotational movements of the body, and the vestibular sacs sense linear accelerations. The vestibular system sends signals to the neural structures that control eye movement and to the muscles that keep the body upright.

Experiencing pain

We do not enjoy it, but the experience of pain is how the body informs us that we are in danger. The burn when we touch a hot radiator and the sharp stab when we step on a nail lead us to change our behaviour, preventing further damage to our bodies. People who cannot experience pain are in serious danger of damage from wounds that others with pain would quickly notice and attend to.

Nociceptors are nerve endings in organs, such as the skin, that respond to discomfort. They transmit pain messages to the central nervous system. The type of pain that we experience is related to the type of nerve fibres that transmit the pain messages. Fast fibres are responsible for the sudden sharp pain that we experience when we get a splinter, for example, while slow fibres are responsible for more chronic, dull pain. If you fall down, fast fibres will ensure you feel the initial painful shock, while slow fibres will result in the dull ache in your limbs that you are left with. Both fast and slow fibres send messages to the brain via the spinal chord.

The gate control theory of pain proposes that pain is determined by the operation of two types of nerve fibres in the spinal cord. One set of smaller nerve fibres carries pain messages from the body to the brain, whereas a second set of larger fibres conducts sensory information about a variety of signals, not just pain. Other sensations, for example, such as rubbing, tickling, and so on, are also processed by the large fibres. Thus, large fibres act as a gate; they stop or start, as a gate would open or close, the flow of pain (Melzack & Wall, 1996). It is for this reason that massaging an area where you feel pain may help alleviate it. The massage activates the large nerve fibres that block the pain signals of the small nerve fibres (Wall, 2000).

Experiencing pain is a lot more complicated than simply responding to neural messages, however. It is also a matter of perception. We feel pain less when we are busy focusing on a challenging activity (Bantick et al., 2002), which can help explain why sports players may feel their injuries only after the game. We also feel less pain when we are distracted by humour (Zweyer, Velker, & Ruch, 2004). Pain is soothed by the brain’s release of endorphins, which are natural, hormonal pain killers. The release of endorphins can explain the euphoria experienced in the running of a marathon (Sternberg, Bailin, Grant, & Gracely, 1998). There are also individual differences in people’s perception of pain.

Key Takeaways

- The ability to taste, smell, and touch are important because they help us avoid harm from environmental toxins.

- The many taste buds on our tongues and inside our mouths allow us to detect six basic taste sensations: sweet, salty, sour, bitter, piquancy, and umami.

- In olfaction, transduction occurs as airborne chemicals that are inhaled through the nostrils are detected by receptors in the olfactory membrane. Different chemical molecules fit into different receptor cells, creating different smells.

- The ability to smell diminishes with age, and, on average, women have a better sense of smell than men.

- We have a range of different nerve endings embedded in the skin, combinations of which respond to the four basic sensations of pressure, hot, cold, and pain. However, only the sensation of pressure has its own specialized receptors.

- Proprioception is our ability to sense the positions and movements of our body parts. Postural and movement information is detected by special neurons located in the skin, joints, bones, ears, and tendons, which pick up messages from the compression and the contraction of muscles throughout the body.

- The vestibular system, composed of structures in the inner ear, monitors the head’s position and movement, maintaining the body’s balance.

- Nociceptors are involved in the experience of pain. Gate control theory explains how large and small neurons work together to transmit and regulate the message of pain to the brain.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Think of the foods that you like to eat the most. Which of the six taste sensations do these foods have, and why do you think that you like these particular flavours?

- Why do you think that women might have a better developed sense of smell than do men?

- Why is experiencing pain a benefit for human beings?

Image Attributions

Figure 5.20. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 5.21. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 5.22. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

Bantick, S. J., Wise, R. G., Ploghaus, A., Clare, S., Smith, S. M., & Tracey, I. (2002). Imaging how attention modulates pain in humans using functional MRI. Brain: A Journal of Neurology, 125(2), 310–319.

Baysinger, C. M., Plubell, P. E., & Harlow, H. F. (1973). A variable-temperature surrogate mother for studying attachment in infant monkeys. Behavior Research Methods & Instrumentation, 5(3), 269–272.

Bensafi, M., Zelano, C., Johnson, B., Mainland, J., Kahn, R., & Sobel, N. (2004). Olfaction: From sniff to percept. In M. S. Gazzaniga (Ed.), The cognitive neurosciences (3rd ed., pp. 259–280). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Feldman, R. (2007). Maternal-infant contact and child development: Insights from the kangaroo intervention. In L. L’Abate (Ed.), Low-cost approaches to promote physical and mental health: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 323–351). New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media.

Field, T., Lasko, D., Mundy, P., Henteleff, T., Kabat, S., Talpins, S., & Dowling, M. (1997). Brief report: Autistic children’s attentiveness and responsivity improve after touch therapy. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 27(3), 333–338.

Haradon, G., Bascom, B., Dragomir, C., & Scripcaru, V. (1994). Sensory functions of institutionalized Romanian infants: A pilot study. Occupational Therapy International, 1(4), 250–260.

Ikeda, K. (1909/2002). New seasonings. Chemical Senses, 27(9), 847–849. Translated and shortened to 75% by Y. Ogiwara & Y. Ninomiya from the Journal of the Chemical Society of Tokyo, 30, 820–836. (Original work published 1909)

Kelling, S. T., & Halpern, B. P. (1983). Taste flashes: Reaction times, intensity, and quality. Science, 219, 412–414.

Keltner, D. (2009). Born to be good: The science of a meaningful life. New York, NY: Norton.

Malnic, B., Hirono, J., Sato, T., & Buck, L. B. (1999). Combinatorial receptor codes for odors. Cell, 96, 713–723.

Melzack, R., & Wall, P. (1996). The challenge of pain. London, England: Penguin.

Murphy, C. (1986). Taste and smell in the elderly. In H. L. Meiselman & R. S. Rivlin (Eds.), Clinical measurement of taste and smell (Vol. 1, pp. 343–371). New York, NY: Macmillan.

Northcutt, R. G. (2004). Taste buds: Development and evolution. Brain, Behavior and Evolution, 64(3), 198–206.

Sternberg, W. F., Bailin, D., Grant, M., & Gracely, R. H. (1998). Competition alters the perception of noxious stimuli in male and female athletes. Pain, 76(1–2), 231–238.

Sugimoto, K., & Ninomiya, Y. (2005). Introductory remarks on umami research: Candidate receptors and signal transduction mechanisms on umami. Chemical Senses, 30(Suppl. 1), Pi21–i22.

Wall, P. (2000). Pain: The science of suffering. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Zweyer, K., Velker, B., & Ruch, W. (2004). Do cheerfulness, exhilaration, and humor production moderate pain tolerance? A FACS study. Humor: International Journal of Humor Research, 17(1-2), 85–119.