13.2 Infancy and Childhood: Exploring, Learning, and Relating

Learning Objectives

- Describe the abilities that newborn infants possess and how they actively interact with their environments.

- Describe attachment.

- Describe some types of parenting behaviours and their associations with children’s behaviours.

- Describe social and emotional competence in early childhood.

- List the stages in Piaget’s model of cognitive development, and explain the concepts that are mastered in each stage.

- Describe other theories that complement and expand on Piaget’s theory.

In a full term pregnancy, a baby is born sometime around the 38th week. The fetus is responsible, at least in part, for its own birth because chemicals released by the developing fetal brain trigger the muscles in the mother’s uterus to start the rhythmic contractions of childbirth. The contractions are initially spaced at about 15-minute intervals but come more rapidly with time. When the contractions reach an interval of two to three minutes, the mother is requested to assist in the labour and help push the baby out.

The newborn arrives with many behaviours intact

Newborns are already prepared to face the new world they are about to experience. As you can see in the table below, babies are equipped with a variety of reflexes, each providing an ability that will help them survive their first few months of life as they continue to learn new routines to help them survive in, and manipulate, their environments.

| Name | Stimulus | Response | Significance | Video Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rooting reflex | The baby’s cheek is stroked. | The baby turns its head toward the stroking, opens its mouth, and tries to suck. | Ensures the infant will find a nipple |

The Rooting Reflex (infantopia, 2009)

|

| Blink reflex | A light is flashed in the baby’s eyes. | The baby closes both eyes. | Protects eyes from strong and potentially dangerous stimuli |

Cute Baby Blinking (eminemloca8, 2007)

|

| Withdrawal reflex | A soft pinprick is applied to the sole of the baby’s foot. | The baby flexes the leg. | Keeps the exploring infant away from painful stimuli |

Baby Withdrawal Reflex (betapicts, 2010)

|

| Tonic neck reflex | The baby is laid down on its back. | The baby turns its head to one side and extends the arm on the same side. | Helps develop hand-eye coordination | 17Primitive Reflexes Asymmetric Tonic Neck (daihocyduoc, 2009) |

| Grasp reflex | An object is pressed into the palm of the baby. | The baby grasps the object pressed and can even hold its own weight for a brief period. | Holding on to prevent falling |

Grasp Reflex (qumar81, 2009)

|

| Moro reflex | Loud noises or a sudden drop in height while holding the baby. | The baby extends arms and legs and quickly brings them in as if trying to grasp something. | Protects from falling; could have assisted infants in holding on to their mothers during rough travelling | Moro Reflex (qumar81, 2009) |

| Stepping reflex | The baby is suspended with bare feet just above a surface and is moved forward. | Baby makes stepping motions as if trying to walk. | Preparedness for walking |

Stepping Reflex (qumar81, 2009)

|

In addition to reflexes, newborns have preferences. They like sweet-tasting foods at first, while becoming more open to salty items by four months of age (Beauchamp, Cowart, Menellia, & Marsh, 1994; Blass & Smith, 1992). Newborns also prefer the smell of their mothers. An infant only six days old is significantly more likely to turn toward its own mother’s breast pad than to the breast pad of another baby’s mother (Porter, Makin, Davis, & Christensen, 1992), and a newborn also shows a preference for the face of its own mother (Bushnell, Sai, & Mullin, 1989).

Although infants are born ready to engage in some activities, they also contribute to their own development through their own behaviours. The child’s knowledge and abilities increase as it babbles, talks, crawls, tastes, grasps, plays, and interacts with the objects in the environment (Gibson, Rosenzweig, & Porter, 1988; Gibson & Pick, 2000; Smith & Thelen, 2003). Parents may help in this process by providing a variety of activities and experiences for the child. Research has found that animals raised in environments with more novel objects and that engage in a variety of stimulating activities have more brain synapses and larger cerebral cortexes, and they perform better on a variety of learning tasks compared with animals raised in more impoverished environments (Juraska, Henderson, & Müller, 1984). Similar effects are likely occurring in children who have opportunities to play, explore, and interact with their environments (Soska, Adolph, & Johnson, 2010).

Contact comfort

One of the key needs of babies is contact comfort: being held, comforted, and cuddled. In a classic study, Wisconsin University psychologists Harry and Margaret Harlow (1958) investigated the responses of young monkeys, separated from their biological mothers, to two surrogate mothers introduced to their cages. One — the wire mother — consisted of a round wooden head, a mesh of cold metal wires, and a bottle of milk from which the baby monkey could drink. The second mother was a foam-rubber form wrapped in a heated terry-cloth blanket. The Harlows found that although the infant monkeys went to the wire mother for food, they overwhelmingly preferred and spent significantly more time with the warm, terry-cloth mother that provided no food but did provide comfort, especially when they were scared (Harlow, 1958).

The following YouTube link provides a good example of contact comfort:

- Video: Harlow’s Studies on Dependency in Monkeys (@MichaelDBaker, n.d.)

Attachment

As they are cuddled and comforted by their caregivers, babies are also developing an attachment style. One of the most important milestones in infancy is the development of attachment to a caregiver. Attachment develops gradually, as infants begin to understand who responds consistently and sensitively to their needs by feeding them, cuddling them, and so on. Attachment is important for survival and helps babies thrive (see Figure 13.2). As attachment develops, it becomes the child’s first “relationship,” and early attachments may provide the model for other emotionally close relationships in life (Cassidy & Shaver, 1999).

Attachment begins to be most evident around six to eight months of age. Most children at this age show stranger anxiety, which is a fearful response to strangers that can range from simply turning the head away to full-out crying. This response is showing that babies are discriminating between someone they know well (e.g., the caregiver) and someone they do not (e.g., the stranger). If the caregiver leaves the baby, either alone or with a stranger, they are likely to show separation anxiety. It is normal for babies to feel and show this distress, much to the chagrin of parents who often want their baby to make friends with an out-of-town relative. Separation anxiety can be difficult for both babies and parents, as it can last for a couple of years.

As late as the 1930s, psychologists believed that children who were raised in institutions such as orphanages and who received good physical care and proper nourishment, would develop normally, even if they had little interaction with their caretakers. However, studies by the developmental psychologist John Bowlby (1953) and others showed that these children did not develop normally — they were usually sickly, emotionally slow, and generally unmotivated. These observations helped make it clear that normal infant development requires successful attachment with a caretaker.

Developmental psychologist Mary Ainsworth, a student of John Bowlby, was interested in studying the development of attachment in infants. Ainsworth created a laboratory test that measured an infant’s attachment to their parent; this was assessed in a situation where the caregiver and a stranger move in and out of the environment. The test is called the strange situation because it is conducted in a context that is unfamiliar to the child and therefore likely to heighten the child’s need for their parent (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978). During the procedure, which lasts about 20 minutes, the parent and the infant are first left alone, while the infant explores the room full of toys. Then, a strange adult enters the room and talks for a minute to the parent, after which the parent leaves the room. The stranger stays with the infant for a few minutes, the parent again enters, and the stranger leaves the room. During the entire session, a video camera records the child’s behaviours, which are later coded by trained coders.

The following YouTube link provides a good example of attachment:

- Video: The Strange Situation – Mary Ainsworth (thibs44, 2009)

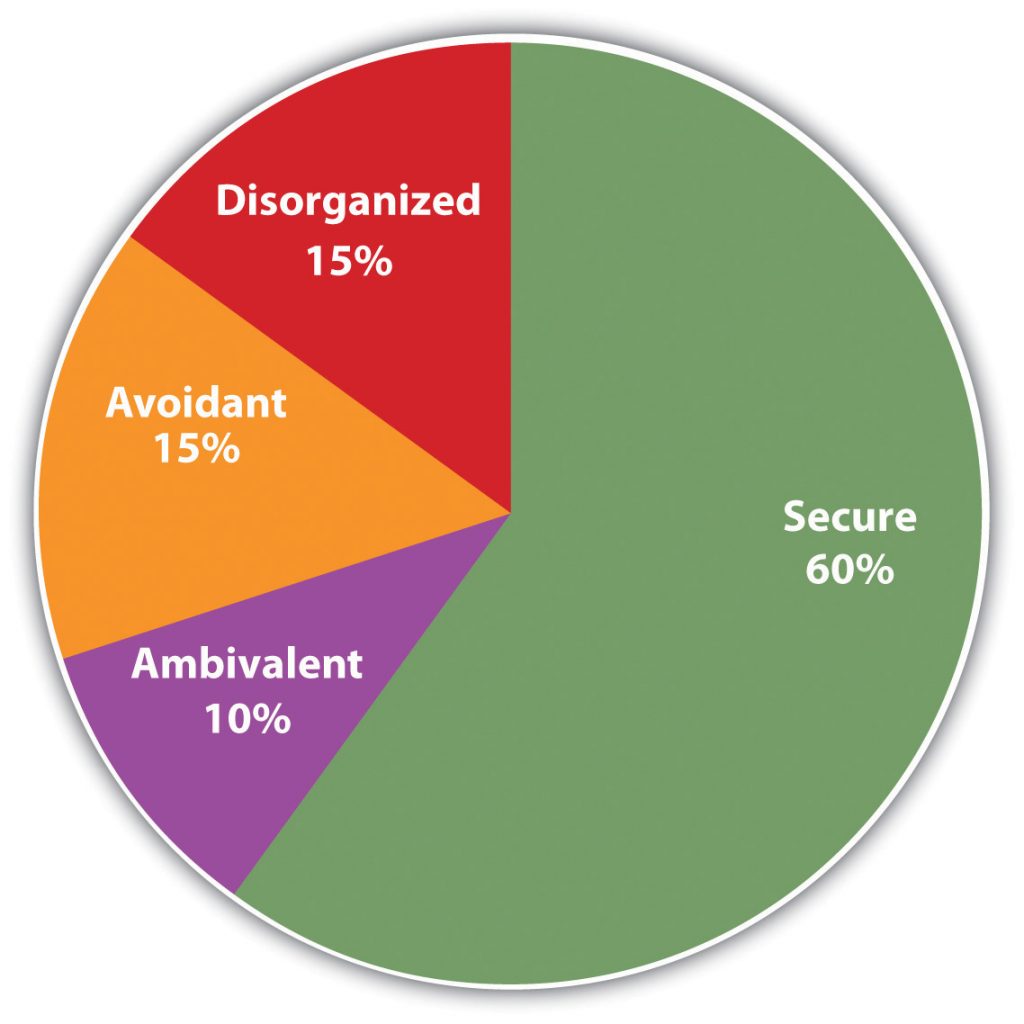

On the basis of their behaviours, the children are categorized into one of four attachment styles, where each reflects a different kind of attachment relationship with the caregiver. A child with a secure attachment style usually explores freely while the mother is present and engages with the stranger. The child is upset when the mother departs and refuses to engage with the stranger, displaying stranger anxiety, but the child is comforted and happy when the mother returns. Most children who have been studied display a secure attachment style (see Figure 13.3).

A child with an ambivalent attachment style, sometimes called insecure-resistant, stays close or even clings to the mother rather than exploring the toys when the stranger is present. When the mother leaves, the child is extremely distressed and is ambivalent when she returns. The child may rush to the mother but then fail to cling to her when she picks up the child. A child with an avoidant attachment style, sometimes called insecure-avoidant, will avoid or ignore the mother, showing little emotion when the mother departs or returns. The child may run away from the mother when she approaches. The child will not explore very much, regardless of who is there, and the stranger will not be treated much differently from the mother.

Finally, a child with a disorganized attachment style seems to have no consistent way of coping with the stress of the strange situation. The child may cry during the separation but avoid the mother when she returns, or the child may approach the mother but then freeze or fall to the floor. Although some cultural differences in attachment styles have been found (Rothbaum, Weisz, Pott, Miyake, & Morelli, 2000), research has also found that the proportion of children who fall into each of the attachment categories is relatively constant across cultures.

You might wonder whether differences in attachment style are determined more by the child (i.e., nature) or more by the parents (i.e., nurture). Most developmental psychologists believe that socialization is primary, arguing that a child becomes securely attached when the mother is available and able to meet the needs of the child in a responsive and appropriate manner, but the insecure styles occur when the mother is insensitive and responds inconsistently to the child’s needs. Given that most children show secure attachment, a wide variety of caregiver behaviours show consistency and sensitivity in responsiveness. In a direct test of this idea, Dutch researcher Dymphna van den Boom (1994) randomly assigned some babies’ mothers to a training session in which they learned to better respond to their children’s needs. The research found that these mothers’ babies were more likely to show a secure attachment style compared with the babies of the mothers in a control group that did not receive training.

The attachment behaviour of the child is also likely influenced, at least in part, by temperament. Temperament in children refers to the characteristic mood, activity level, attention span, and level of distractability that is evident in infancy and early childhood (Rothbart & Bates, 2005; Thomas & Chess, 1977). Some children are warm, friendly, and responsive, whereas others tend to be more irritable, less manageable, and difficult to console. These differences may also play a role in attachment (Gillath, Shaver, Baek, & Chun, 2008; Seifer, Schiller, Sameroff, Resnick, & Riordan, 1996).

Although temperament is biologically based, it interacts with the influence of experience from the moment of birth, if not before, to shape personality (Rothbart, 2011). Temperamental dispositions are affected, for example, by the support level of parental care. More generally, personality is shaped by the goodness of fit between the child’s temperamental qualities and characteristics of the environment (Chess & Thomas, 1999). For example, an adventurous child whose parents regularly take them on weekend hiking and fishing trips would be a good “fit” to their lifestyle, supporting personality growth. Personality is the result, therefore, of the continuous interplay between biological disposition and experience, as is true for many other aspects of social and personality development.

Personality develops from temperament in other ways (Thompson, Winer, & Goodvin, 2010). As children mature biologically, temperamental characteristics emerge and change over time. A newborn is not capable of much self-control, but as brain-based capacities for self-control advance, temperamental changes in self-regulation become more apparent. For example, a newborn who cries frequently does not necessarily have a grumpy personality; over time, with sufficient parental support and increased sense of security, the child might be less likely to cry.

In addition, personality is made up of many other features besides temperament. Children’s developing self-concept, their motivations to achieve or to socialize, their values and goals, their coping styles, their sense of responsibility and conscientiousness, and many other qualities are encompassed into personality. These qualities are influenced by biological dispositions, but even more by the child’s experiences with others, particularly in close relationships, that guide the growth of individual characteristics.

Indeed, personality development begins with the biological foundations of temperament but becomes increasingly elaborated, extended, and refined over time. The newborn that parents gazed upon thus becomes an adult with a personality of depth and nuance.

The influence of parents

Following the development of attachment in the child’s early years, parents continue to play a role in shaping their children. The relative influences of parenting and genetics on things like personality, intelligence, morality, and so on are complicated to study empirically. Much research done with children cannot separate out these effects because we cannot do experiments that alter the parents or substantially alter parenting styles in order to see the effects on children, and being able to control for the effects of genes and environments requires children who are genetically identical (i.e., identical twins) or adopted to participate in the study. Twin and adoption studies are expensive, time-consuming, and complex. Thus, the research on the influence of parenting on children is largely correlational; as we have already learned, correlational studies show us associations between variables, but they cannot be used to make definitive statements about cause and effect.

As all parents eventually discover, there is no step-by-step guide that provides foolproof advice on all of the challenges of parenting; the effects of parenting practices vary at least partly because children are different. Children whose temperament might be described as easygoing might require different parenting strategies than children who are easily upset, distressed, fearful, or volatile. Part of the challenge for parents is recognizing these temperamental challenges of individual children and adapting their own temperaments to fit.

One of the areas that parents have to navigate is the use of discipline to shape children’s behaviour. All parents are faced with children who misbehave. Research suggests some ways of responding to child misbehaviour may be better than others. Power assertion is when parents try to correct children’s misbehaviour through the use of punishment, threats, and their superior power. While there are times when, for example, child safety requires this sort of discipline, using power assertion consistently may do little to teach children about the desired behaviour of the effects of their behaviour on others, and it may result in children simply obeying when the parent is present so they avoid punishment. If power assertion is coupled with physical punishment, this may cause children to obey out of fear. Physical punishment is generally seen as undesirable because it creates an atmosphere of fear, hostility, aggression, and anger. For more on this, the undesirable effects of physical punishment are investigated in greater detail by Elizabeth Gershoff (2002).

An alternative to power assertion is induction. Induction involves the correction of children’s misbehaviour by showing them how and why they were wrong, explaining the effects of their behaviour on others, and showing understanding of the child’s emotions. Induction involves the activation of the child’s empathy. Induction tends to help children develop better self-regulation and internalize a sense of morality. Induction is more likely to maintain a child’s self-esteem because it validates the child’s understanding of the situation while at the same time allowing for it to be corrected in a gentle way.

It is likely that parents use both power assertion and induction at times. It is also possible that aspects of children may elicit these different strategies from parents and that situational demands may also call for different strategies. As well, cultures differ in their accepted standards of child discipline. There is no doubt that parents use discipline with the best of intentions and that psychologists will continue to try to understand what long-term effects may exist.

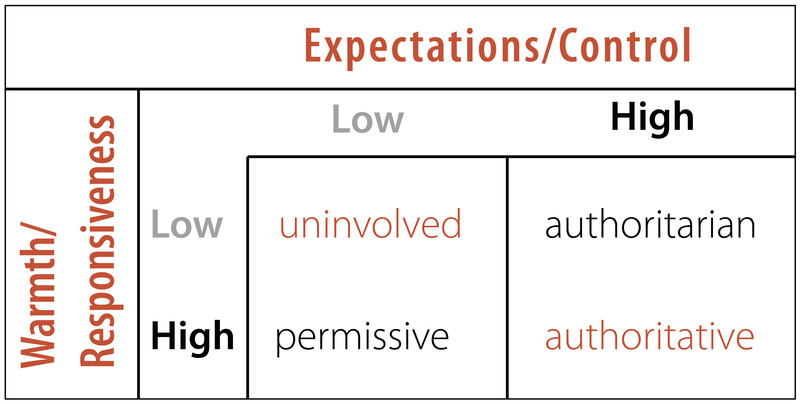

As children mature, parent-child relationships naturally change. Preschool and grade-school children are more capable, have their own preferences, and sometimes refuse or seek to compromise with parental expectations. This can lead to greater parent-child conflict, and how conflict is managed by parents further shapes the quality of parent-child relationships. In general, children develop greater competence and self-confidence when parents have high, but reasonable, expectations for children’s behaviour, communicate well with them, are warm and responsive, and use reasoning, rather than coercion, as preferred responses to children’s misbehaviour. This kind of parenting style has been described as authoritative (Baumrind, 2013). Authoritative parents are supportive and show interest in their kids’ activities but are not overbearing and allow them to make constructive mistakes. By contrast, some less-constructive parent-child relationships result from authoritarian, uninvolved, or permissive parenting styles (see Figure 13.4).

Parental roles in relation to their children change in other ways, too. Parents increasingly become mediators, also considered gatekeepers, of their children’s involvement with peers and activities outside the family. Their communication and practice of values contribute to children’s academic achievement, moral development, and activity preferences. As children reach adolescence, the parent-child relationship increasingly becomes one of “co-regulation,” in which both the parent(s) and the child recognizes the child’s growing competence and autonomy, and together they rebalance authority relations. We often see evidence of this as parents start accommodating their teenage kids’ sense of independence by allowing them to get cars, jobs, attend parties, and stay out later.

Family relationships are significantly affected by conditions outside the home. For instance, the Family Stress Model describes how financial difficulties are associated with parents’ depressed moods, which in turn lead to marital problems and poor parenting, which in turn contributes to poorer child adjustment (Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010). Within the home, parental marital difficulty or divorce affects more than half the children growing up today in the Canada and the United States. Divorce is typically associated with economic stresses for children and parents, the renegotiation of parent-child relationships with one parent typically as primary custodian and the other assuming a visiting relationship, and many other significant adjustments for children. Divorce is often regarded by children as a sad turning point in their lives, although for most it is not associated with long-term problems of adjustment (Emery, 1999).

Knowing the self: The development of the self-concept

One of the important milestones in a child’s social development is learning about their own self-existence (see Figure 13.5). This self-awareness is known as consciousness, and the content of consciousness is known as the self-concept. The self-concept is a knowledge representation or schema that contains knowledge about us, including our beliefs about our personality traits, physical characteristics, abilities, values, goals, and roles, as well as the knowledge that we exist as individuals (Kagan, 1991).

Some animals, including chimpanzees, orangutans, and perhaps dolphins, have at least a primitive sense of self (Boysen & Himes, 1999). In one study (Gallup, 1970), researchers painted a red dot on the foreheads of anesthetized chimpanzees and then placed each animal in a cage with a mirror. When the chimps woke up and looked in the mirror, they touched the dot on their faces, not the dot on the faces in the mirror. These actions suggest that the chimps understood that they were looking at themselves and not at other animals; thus, we can assume that they are able to realize that they exist as individuals. On the other hand, most other animals, including, for instance, dogs, cats, and monkeys, never realize that it is themselves in the mirror.

Infants who have a similar red dot painted on their foreheads recognize themselves in a mirror in the same way that the chimps do, and they do this by about 18 months of age (Povinelli, Landau, & Perilloux, 1996). The child’s knowledge about the self continues to develop as the child grows. By age two, the infant becomes aware of their sex. By age four, self-descriptions are likely to be based on physical features, such as hair colour and possessions, and by about age six, the child is able to understand basic emotions and the concepts of traits, being able to make statements such as “I am a nice person” (Harter, 1998).

Soon after children enter school, at about age five or six, they begin to make comparisons with other children, a process known as social comparison. For example, a child might describe themself as being faster than one child but slower than another (Moretti & Higgins, 1990). According to Erik Erikson (1950), the important component of this process is the development of competence and autonomy — the recognition of one’s own abilities relative to other children. Children increasingly show awareness of social situations; they understand that other people are looking at and judging them the same way that they are looking at and judging others (Doherty, 2009).

Social and emotional competence

Social and personality development is built from the social, biological, and representational influences discussed above. These influences result in important developmental outcomes that matter to children, parents, and society. Some of the developmental outcomes that denote social and emotional competence include a young adult’s capacity to engage in socially constructive actions (e.g., helping, caring, and sharing with others), to curb hostile or aggressive impulses, to live according to meaningful moral values, to develop a healthy identity and sense of self, and to develop talents and achieve success in using them.

These achievements of social and personality development derive from the interaction of many social, biological, and representational influences. Consider, for example, the development of conscience, which is an early foundation for moral development. Conscience consists of the cognitive, emotional, and social influences that cause young children to create and act consistently with internal standards of conduct (Kochanska, 2002). Conscience emerges from young children’s experiences with parents, particularly in the development of a mutually responsive relationship that motivates young children to respond constructively to the parents’ requests and expectations. Biologically based temperament is involved, as some children are temperamentally more capable of motivated self-regulation than are others, a quality called effortful control. However, some children are dispositionally more prone to the fear and anxiety that parental disapproval can evoke. Conscience development grows through a good fit between the child’s temperamental qualities and how parents communicate and reinforce behavioural expectations. Moreover, as an illustration of the interaction of genes and experience, one research group found that young children with a particular gene allele, the 5-HTTLPR, were low on measures of conscience development when they had previously experienced unresponsive maternal care, but children with the same allele growing up with responsive care showed strong later performance on conscience measures (Kochanska, Kim, Barry, & Philibert, 2011).

Conscience development also expands as young children begin to represent moral values and think of themselves as moral beings. By the end of the preschool years, for example, young children develop a “moral self” by which they think of themselves as people who want to do the right thing, who feel badly after misbehaving, and who feel uncomfortable when others misbehave. In the development of conscience, young children become more socially and emotionally competent in a manner that provides a foundation for later moral conduct (Thompson, 2012).

Understanding infant knowledge

It may seem to you that babies have little ability to understand or remember the world around them. Indeed, the famous psychologist William James presumed that the newborn experiences a “blooming, buzzing confusion” (James, 1890, p. 462). You may think that, even if babies do know more than James gave them credit for, it might not be possible to find out what they know. After all, infants cannot talk or respond to questions, so how would we ever find out? Over the past two decades, developmental psychologists have created new ways to determine what babies know, and they have found that they know much more than you, or William James, might have expected.

One way that we can learn about the cognitive development of babies is by measuring their behaviour in response to the stimuli around them. For instance, some researchers have given babies the chance to control which shapes they get to see or which sounds they get to hear according to how hard they suck on a pacifier (Trehub & Rabinovitch, 1972). The sucking behaviour is used as a measure of the infants’ interest in the stimuli, and the sounds or images they suck hardest in response to are the ones we can assume they prefer.

Another approach to understanding cognitive development by observing the behaviour of infants is through the use of the habituation technique. Habituation refers to the decreased responsiveness toward a stimulus after it has been presented numerous times in succession. Organisms, including infants, tend to be more interested in things the first few times they experience them and become less interested in them with more frequent exposure. Developmental psychologists have used this general principle to help them understand what babies remember and understand.

Habituation involves exposing an infant to a stimulus repeatedly. Each time the infant is exposed to the stimulus, the amount of time they spend attending to it is measured. With repeated presentations of the stimulus, babies spend less time attending to it. In other words, they get bored and stop paying attention. If the stimulus is changed slightly, researchers can tell that babies recognize this difference because the time they spend attending to it goes up again. Thus, it can be said that babies have “learned” something about the first stimulus in order to “know” that the second stimulus is different; dishabituation is seen in the latter.

The following YouTube link provides a good example of infant knowledge:

- Video: Infant Looking Time Habituation. Activity 2 from “What Babies Can Do” DVD (powerbabies, 2011)

The habituation procedure allows researchers to create variations that reveal a great deal about a newborn’s cognitive ability. The trick is simply to change the stimulus in controlled ways to see if the baby notices the difference. Research using the habituation procedure has found that babies can notice changes in colours, sounds, and even principles of numbers and physics.

Cognitive development during childhood — Piaget’s theory

Childhood is a time in which changes occur quickly. The child is growing physically, and cognitive abilities are also developing. During this time, the child learns to actively manipulate and control aspects of their environment and is first exposed to the requirements of society, particularly the need to control the bladder and bowels. According to Erikson (1950), the challenges that the child must attain in childhood relate to the development of initiative, competence, and independence; children need to learn to explore the world, to become self-reliant, and to make their own way in the environment.

These skills do not come overnight. Neurological changes during childhood provide children the ability to do some things at certain ages while making it impossible for them to do other things. This fact was made apparent through the groundbreaking work of the Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget (see Figure 13.6). During the 1920s, Piaget was administering intelligence tests to children in an attempt to determine the kinds of logical thinking that children were capable of. In the process of testing them, Piaget became intrigued, not so much by the answers that the children got right, but more by the answers they got wrong. Piaget believed that the incorrect answers the children gave were not mere shots in the dark but rather represented specific ways of thinking unique to the children’s developmental stage. Just as almost all babies learn to roll over before they learn to sit up by themselves and learn to crawl before they learn to walk, Piaget believed that children gain their cognitive ability in a developmental order. These insights — that children at different ages think in fundamentally different ways — led to Piaget’s stage model of cognitive development.

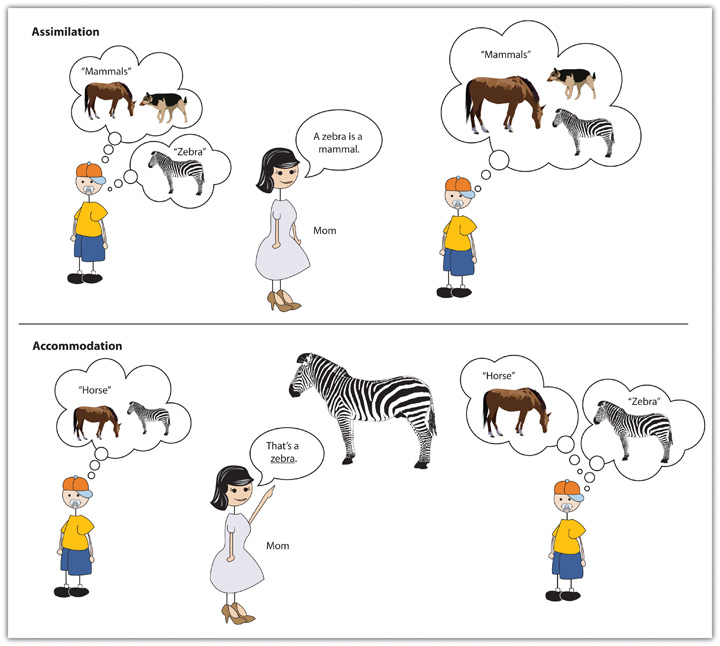

Piaget (1952) argued that children do not just passively learn but also actively try to make sense of their worlds. He argued that, as they learn and mature, children develop schemas — patterns of knowledge in long-term memory — that help them remember, organize, and respond to information. Furthermore, Piaget thought that when children experience new things, they attempt to reconcile the new knowledge with existing schemas. Piaget believed that children use two distinct methods in doing so, methods that he called assimilation and accommodation (see Figure 13.7).

When children employ assimilation, they use already developed schemas to understand new information. If children have learned a schema for horses, then they may call the striped animal they see at the zoo a horse rather than a zebra. In this case, children fit the existing schema to the new information and label the new information with the existing knowledge. Accommodation, on the other hand, involves learning new information and thus changing the schema. When a mother says, “No, honey. That’s a zebra, not a horse,” the child may adapt the schema to fit the new stimulus, learning that there are different types of four-legged animals, only one of which is a horse.

Piaget’s most important contribution to understanding cognitive development, and the fundamental aspect of his theory, was the idea that development occurs in unique and distinct stages, with each stage occurring at a specific time, in a sequential manner, and in a way that allows the child to think about the world using new capacities. Piaget’s stages of cognitive development are summarized in the table below.

| Stage | Approximate Age Range | Characteristics | Key Attainments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensorimotor | Birth to about two years | The child experiences the world through the fundamental senses of seeing, hearing, touching, and tasting. | Object permanence |

| Preoperational | Two to seven years | Children acquire the ability to internally represent the world through language and mental imagery. They are egocentric, have trouble reversing mental operations, and are developing a theory of mind. | Understands symbols |

| Concrete operational | Seven to 11 years | Children become able to think logically, overcoming the shortcomings of preoperational thought. They have trouble with abstract concepts. | Conservation; logical thinking |

| Formal operational | Eleven years to adulthood | Adolescents can think systematically, can reason about abstract concepts, and can understand ethics and scientific reasoning. | Abstract logic |

The first developmental stage for Piaget was the sensorimotor stage, the cognitive stage that begins at birth and lasts until around the age of two. It is defined by the direct physical interactions that babies have with the objects around them. During this stage, babies form their first schemas by using their primary senses. They stare at, listen to, reach for, hold, shake, and taste the things in their environments.

During the sensorimotor stage, babies use of their senses to perceive the world is so central to their understanding that whenever babies do not directly perceive objects, as far as they are concerned, the objects do not exist. Piaget found, for instance, that if he first interested babies in a toy and then covered the toy with a blanket, children who were younger than six months of age would act as if the toy had disappeared completely; they never tried to find it under the blanket but would nevertheless smile and reach for it when the blanket was removed. Piaget found that it was not until about eight months that the children realized that the object was merely covered and not gone. Piaget used the term object permanence to refer to the child’s ability to know that an object exists even when the object cannot be perceived.

The following YouTube link provides a demonstration of object permanence:

- Video: Piaget – Object Permanence Failure – Sensorimotor Stage (Adam, 2013)

Canadian researcher Renée Baillargeon (Baillargeon, 2004; Wang, Baillargeon, & Brueckner, 2004) expanded the habituation task to take advantage of the tendency of infants to attend to stimuli that they find interesting to see if object permanence existed earlier than eight months of age. While Piaget thought that object permanence was shown in infants’ active physical search of an object that had “disappeared,” Baillargeon’s research showed that object permanence can be shown by measuring infant gaze and that it appears earlier than eight months.

The following YouTube link provides a good example of object permanence:

- Video: Object Concept VOE Ramp Study Baillargeon (Adam, 2013)

At about two years of age, and until about seven years of age, children move into the preoperational stage. During this stage, children begin to use language and to think more abstractly about objects with capacity to form mental images; however, their understanding is more intuitive, and they lack much ability to deduce or reason. The thinking is preoperational, meaning that the child lacks the ability to operate on or transform objects mentally. In one study that showed the extent of this inability, Judy DeLoache (1987) showed children a room within a small dollhouse. Inside the room, a small toy was visible behind a small couch. The researchers took the children to another lab room, which was an exact replica of the dollhouse room, but full-sized. When children who were two-and-half years old were asked to find the toy, they did not know where to look; they were simply unable to make the transition across the changes in room size. Three-year-old children, on the other hand, immediately looked for the toy behind the couch, demonstrating that they were improving their operational skills.

The inability of young children to view transitions also leads them to be egocentric — that is, unable to readily see and understand other people’s viewpoints. Developmental psychologists define the theory of mind as the ability to take another person’s viewpoint, and the ability to do so increases rapidly during the preoperational stage. In one demonstration of the development of theory of mind, a researcher shows a child a video of another child — let’s call her Anna — putting a ball in a red box. Then, Anna leaves the room, and the video shows that while she is gone, a researcher moves the ball from the red box into a blue box. As the video continues, Anna comes back into the room. The child is then asked to point to the box where Anna will probably look to find her ball. Children who are younger than four years of age typically are unable to understand that Anna does not know that the ball has been moved, and they predict that she will look for it in the blue box. After four years of age, however, children have developed a theory of mind; they realize that different people can have different viewpoints and that, although she will be wrong, Anna will nevertheless think that the ball is still in the red box.

After about seven years of age until 11, the child moves into the concrete operational stage, which is marked by more frequent and more accurate use of transitions, operations, and abstract concepts, including those of time, space, and numbers. An important milestone during the concrete operational stage is the development of conservation, which is the understanding that changes in the form of an object do not necessarily mean changes in the quantity of the object. Children younger than seven years generally think that a glass of milk that is tall holds more milk than a glass of milk that is shorter and wider, and they continue to believe this even when they see the same milk poured back and forth between the glasses. It appears that these children focus only on one dimension — in this case, the height of the glass — and ignore the other dimension — such as width. However, when children reach the concrete operational stage, their abilities to understand such transformations make them aware that, although the milk looks different in the different glasses, the amount must be the same.

At about 11 years of age, children enter the formal operational stage, which is marked by the ability to think in abstract terms and to use scientific and philosophical lines of thought. Children in the formal operational stage are better able to systematically test alternative ideas to determine their influences on outcomes. For instance, rather than haphazardly changing different aspects of a situation that allows no clear conclusions to be drawn, they systematically make changes in one thing at a time and observe what difference that particular change makes. They learn to use deductive reasoning, such as “if this, then that,” and they become capable of imagining situations that might be, rather than just those that actually exist.

The following YouTube link provides good examples of Piaget’s stages:

Piaget’s Stages of Development (misssmith891)

Piaget’s theories have made a substantial and lasting contribution to developmental psychology. His contributions include the idea that children are not merely passive receptacles of information but rather actively engage in acquiring new knowledge and making sense of the world around them. This general idea has generated many other theories of cognitive development, each designed to help us better understand the development of the child’s information-processing skills (Klahr & MacWhinney, 1998; Shrager & Siegler, 1998). Furthermore, the extensive research that Piaget’s theory has stimulated has generally supported his beliefs about the order in which cognition develops. Piaget’s work has also been applied in many domains — for instance, many teachers make use of Piaget’s stages to develop educational approaches aimed at the level children are developmentally prepared for (Driscoll, 1994; Levin, Siegler, & Druyan, 1990).

Piaget may have been surprised about the extent to which a child’s social surroundings influence learning. In some cases, children progress to new ways of thinking and retreat to old ones depending on the type of task they are performing, the circumstances they find themselves in, and the nature of the language used to instruct them (Courage & Howe, 2002). Children in different cultures show somewhat different patterns of cognitive development. Pierre Dasen (1972) found that children in non-Western cultures moved to the next developmental stage about a year later than did children from Western cultures and that level of schooling also influenced cognitive development. In short, Piaget’s theory probably understated the contribution of environmental factors to social development.

Cognitive development during childhood — Vygotsky’s influence

More recent theories (Cole, 1996; Rogoff, 1990; Tomasello, 1999), based in large part on the sociocultural theory of the Russian scholar Lev Vygotsky (1962, 1978), argue that cognitive development is not isolated entirely within the child but occurs at least in part through social interactions. These scholars argue that children’s thinking develops through constant interactions with more competent others, including parents, peers, and teachers.

Vygotsky’s notion that children learn through the guidance of others is termed the zone of proximal development — this refers to the things that children cannot know or do on their own but that are attainable with the sensitive guidance from another person. Vygotsky argued that adults and teachers use scaffolding, which is an understanding of how to provide just enough guidance for a child to accomplish something on their own.

An extension of Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory is the idea of community learning in which children serve as both teachers and learners. This approach is frequently used in classrooms to improve learning as well as to increase responsibility and respect for others. When children work cooperatively in groups to learn material, they can help and support each other’s learning as well as learn about each other as individuals, thereby reducing prejudice (Aronson, Blaney, Stephan, Sikes, & Snapp, 1978; Brown, 1997).

Source: Adapted from Thompson (2020).

Psychology in Everyday Life

What makes a good parent?

Earlier we discussed parenting styles and the classification of four styles based on where they fall along the dimensions of parental control and warmth: uninvolved, authoritarian, permissive, and authoritative. Many studies of children and their parents, using different methods, measures, and samples, have reached the same conclusion — namely, that authoritative parenting, in comparison to the other three styles, is associated with a wide range of psychological and social advantages for children. Parents who use the authoritative style, with its combination of demands on the children as well as responsiveness to the children’s needs, have kids who show better psychological adjustment, school performance, and psychosocial maturity compared with the kids of parents who use the other styles (Baumrind, 1996; Grolnick & Ryan, 1989). On the other hand, there are cultural differences in parenting styles. In a study comparing parenting styles in Canada, France, and Italy, Michael Claes and colleagues at the University of Montreal (Claes et al., 2011) found Canadian parents to be the most tolerant, having fewer rules and disciplinary actions. Canadian mothers and fathers were seen as less punitive, less coercive, and more tolerant than French and Italian mothers. The French were found to parent in a moderate style. French fathers, however, were perceived by teens as emotionally distant, rigid, and prone to intergenerational conflict. French mothers, for their part, were reported to foster closer bonds as their children grew into adolescence. In all three countries, teens experienced a gradual decrease in behavioural control between the ages of 11 and 19, when fathers and mothers reduced requirements and disciplinary constraints. “Our study found parental control is dictated by social codes and culture-specific values, which promote certain parental practices and proscribe others,” says Claes, noting that Canadian parents value a democratic conception of education that promotes independence and negotiation, while European parents, especially Italians, advocate for obligations and respect for parental authority (University of Montreal, 2010, para. 6).

Despite the fact that different parenting styles are differentially effective overall, every child is different, and parents must be adaptable. Some children have particularly difficult temperaments, and these children require different parenting. The behaviours of the parents matter more for the children’s development than they do for other, less demanding children who require less parenting overall (Pluess & Belsky, 2010). These findings remind us how the behaviour of the child can influence the behaviour of the people in their environment.

Although the focus is on the child, the parents must never forget about each other. Parenting is time-consuming and emotionally taxing, and the parents must work together to create a relationship in which both mother and father contribute to the household tasks and support each other. It is also important for the parents to invest time in their own intimacy, as happy parents are more likely to stay together, and divorce has a profoundly negative impact on children, particularly during and immediately after the divorce (Burt, Barnes, McGue, & Iacono, 2008; Ge, Natsuaki, & Conger, 2006).

Key Takeaways

- Babies are born with a variety of skills and abilities that contribute to their survival, and they also actively learn by engaging with their environments.

- Attachment to a caregiver is an important first relationship in life. Attachment styles refer to the security of this relationship and more generally to the type of relationship that people, and especially children, develop with those who are important to them.

- Temperament refers to characteristic mood, activity level, attention span, and level of distractability that is evident in infancy and early childhood. It is the foundation for personality.

- Parents use different types of discipline, such as power assertion and induction, and have parenting styles characterized by levels of warmth and parental control.

- Children’s knowledge of the self is evident as young as 18 months of age.

- By the end of the preschool years, young children’s “moral self” reflects how they think of themselves as people who want to do the right thing, who feel badly after misbehaving, and who feel uncomfortable when others misbehave.

- The habituation technique is used to demonstrate the newborn’s ability to remember and learn from experience.

- Children use both assimilation and accommodation to develop functioning schemas of the world.

- Piaget’s theory of cognitive development proposes that children develop in a specific series of sequential stages: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational.

- Piaget’s theories have had a major impact, but they have also been critiqued and expanded.

- Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory proposes that cognitive development is partly influenced by social interactions with more knowledgeable others.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Give an example of a situation in which you or someone else might show cognitive assimilation and cognitive accommodation. In what cases do you think each process is most likely to occur?

- Consider some examples of how Piaget’s and Vygotsky’s theories of cognitive development might be used by teachers who are teaching young children.

- What advice would you give to new parents who are concerned about their child developing secure attachment?

- Are the gender differences that exist innate (i.e., biological) differences or are they caused by other variables?

Image Attributions

Figure 13.2. MaternalBond by Koivth is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license; An Admirable Dad by Julien Harneis is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license; Szymon i Krystian 003 by Joymaster is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

Figure 13.3. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 13.4. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 13.5. Toddler in Mirror by Samantha Steele is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license; There’s a Monkey in my Mirror by Mor is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 license; Mirror Mirror Who Is the Most Beautiful Dog? by rromer is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 13.6. Jean Piaget by mirjoran is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 13.7. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Long Descriptions

Figure 13.3. In terms of children’s attachment styles, 60% are secure, 15% are disorganized, 15% are avoidant, and 10% are ambivalent.

Figure 13.4. Parenting styles:

| High Demands | Low Demands | |

|---|---|---|

| High Responsiveness | Authoritative parenting | Permissive parenting |

| Low Responsiveness | Authoritarian parenting | Rejecting-neglecting parenting |

References

@MichaelDBaker. (n.d.). Harlow’s studies on dependency in monkeys. [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MmbbfisRiwA

Adam. (2013, February 10). Object concept VOE ramp study baillargeon [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hwgo2O5Vk_g

Adam. (2013, January 21). Piaget – Object permanence failure (Sensorimotor stage) [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rVqJacvywAQ

Ainsworth, M. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Aronson, E., Blaney, N., Stephan, C., Sikes, J., & Snapp, M. (1978). The jigsaw classroom. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Baillargeon, R. (2004). Infants’ physical world. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13(3), 89–94.

Baumrind, D. (1996). The discipline controversy revisited. Family Relations, 45(4), 405–414.

Baumrind, D. (2013). Authoritative parenting revisited: History and current status. In R. E. Larzelere, A. Sheffield, & A. W. Harrist (Eds.), Authoritative parenting: Synthesizing nurturance and discipline for optimal child development (pp. 11–34). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Beauchamp, D. K., Cowart, B. J., Menellia, J. A., & Marsh, R. R. (1994). Infant salt taste: Developmental, methodological, and contextual factors. Developmental Psychology, 27, 353–365.

betapicts. (2010, July 2). Baby withdrawal reflex [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZpDUPDU-5jg

Blass, E. M., & Smith, B. A. (1992). Differential effects of sucrose, fructose, glucose, and lactose on crying in 1- to 3-day-old human infants: Qualitative and quantitative considerations. Developmental Psychology, 28, 804–810.

Bowlby, J. (1953). Some pathological processes set in train by early mother-child separation. Journal of Mental Science, 99, 265–272.

Boysen, S. T., & Himes, G. T. (1999). Current issues and emerging theories in animal cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 683–705.

Brown, A. L. (1997). Transforming schools into communities of thinking and learning about serious matters. American Psychologist, 52(4), 399–413.

Burt, S. A., Barnes, A. R., McGue, M., & Iacono, W. G. (2008). Parental divorce and adolescent delinquency: Ruling out the impact of common genes. Developmental Psychology, 44(6), 1668–1677.

Bushnell, I. W. R., Sai, F., & Mullin, J. T. (1989). Neonatal recognition of the mother’s face. British Journal of developmental psychology, 7, 3–15.

Cassidy, J. E., & Shaver, P. R. E. (1999). Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Chess, S., & Thomas, A. (1999). Goodness of fit: Clinical applications from infancy through adult life. New York, NY: Brunner-Mazel/Taylor & Francis.

Claes, M., Perchec, C., Miranda, D., Benoit, A., Bariaud, F., Lanz, M., . . . Lacourse, É. (2011). Adolescents’ perceptions of parental practices: A cross-national comparison of Canada, France, and Italy. Journal of Adolescence, 34(2), 225–238.

Cole, M. (1996). Culture in mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., & Martin, M. J. (2010). Socioeconomic status, family processes, and individual development. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 685–704

Courage, M. L., & Howe, M. L. (2002). From infant to child: The dynamics of cognitive change in the second year of life. Psychological Bulletin, 128(2), 250–276.

daihocyduoc. (2009, November 15). 17Primitive reflexes asymmetric tonic neck [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UWqafotPxTg

Dasen, P. R. (1972). Cross-cultural Piagetian research: A summary. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 3, 23–39.

DeLoache, J. S. (1987). Rapid change in the symbolic functioning of very young children. Science, 238(4833), 1556–1556.

Doherty, M. J. (2009). Theory of mind: How children understand others’ thoughts and feelings. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Driscoll, M. P. (1994). Psychology of learning for instruction. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Emery, R. E. (1999). Marriage, divorce, and children’s adjustment (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

eminemloca8. (2007, August 29). Cute baby blinking [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=glYohCKsBxI

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York, NY: Norton.

Gallup, G. G., Jr. (1970). Chimpanzees: Self-recognition. Science, 167(3914), 86–87.

Ge, X., Natsuaki, M. N., & Conger, R. D. (2006). Trajectories of depressive symptoms and stressful life events among male and female adolescents in divorced and nondivorced families. Development and Psychopathology, 18(1), 253–273.

Gershoff, E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 539–579.

Gibson, E. J., & Pick, A. D. (2000). An ecological approach to perceptual learning and development. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Gibson, E. J., Rosenzweig, M. R., & Porter, L. W. (1988). Exploratory behavior in the development of perceiving, acting, and the acquiring of knowledge. In Annual review of psychology (Vol. 39, pp. 1–41). Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews.

Gillath, O., Shaver, P. R., Baek, J.-M., & Chun, D. S. (2008). Genetic correlates of adult attachment style. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(10), 1396–1405.

Grolnick, W. S., & Ryan, R. M. (1989). Parent styles associated with children’s self-regulation and competence in school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81(2), 143–154.

Harlow, H. (1958). The nature of love. American Psychologist, 13, 573–685.

Harter, S. (1998). The development of self-representations. In W. Damon & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, & personality development (5th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 553–618). New York, NY: Wiley.

infantopia. (2009, August 5). The rooting reflex (Also, hand to mouth & tongue thrust reflexes) [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=24&v=GDQmakJmHfM

James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology. New York, NY: Dover.

Juraska, J. M., Henderson, C., & Müller, J. (1984). Differential rearing experience, gender, and radial maze performance. Developmental Psychobiology, 17(3), 209–215.

Kagan, J. (1991). The theoretical utility of constructs of self. Developmental Review, 11, 244–250.

Klahr, D., & MacWhinney, B. (1998). Information processing. In D. Kuhn & R. S. Siegler (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Cognition, perception, & language (5th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 631–678). New York, NY: Wiley.

Kochanska, G. (2002). Mutually responsive orientation between mothers and their young children: A context for the early development of conscience. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11, 191–195.

Kochanska, G., Kim, S., Barry, R. A., & Philibert, R. A. (2011). Children’s genotypes interact with maternal responsive care in predicting children’s competence: Diathesis-stress or differential susceptibility? Development and Psychopathology, 23, 605–616.

Levin, I., Siegler, S. R., & Druyan, S. (1990). Misconceptions on motion: Development and training effects. Child Development, 61, 1544–1556.

misssmith891. (n.d.). Piaget’s stages of development [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YtLEWVu815o

Moretti, M. M., & Higgins, E. T. (1990). The development of self-esteem vulnerabilities: Social and cognitive factors in developmental psychopathology. In R. J. Sternberg & J. Kolligian, Jr. (Eds.), Competence considered (pp. 286–314). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children (M. Cook. Trans.). New York, NY: Norton.

Pluess, M., & Belsky, J. (2010). Differential susceptibility to parenting and quality child care. Developmental Psychology, 46(2), 379–390.

Porter, R. H., Makin, J. W., Davis, L. B., & Christensen, K. M. (1992). Breast-fed infants respond to olfactory cues from their own mother and unfamiliar lactating females. Infant Behavior & Development, 15(1), 85–93.

Povinelli, D. J., Landau, K. R., & Perilloux, H. K. (1996). Self-recognition in young children using delayed versus live feedback: Evidence of a developmental asynchrony. Child Development, 67(4), 1540–1554.

powerbabies. (2011, March 24). Infant looking time habituation. Activity 2 from “What Babies Can Do” DVD [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dlilZh60qdA&t=5s

qumar81. (2009, March 14). Grasp reflex [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TidY4XPnFUM

qumar81. (2009, March 14). Moro reflex [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PTz-iVI2mf4

qumar81. (2009, March 14). Stepping reflex [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cZYHwCWSKiE

Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Rothbart, M. K. (2011). Becoming who we are: Temperament and personality in development. New York, NY: Guilford.

Rothbart, M. K., & Bates, J. E. (2005). Temperament. In W. Damon, R. Lerner, & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 99–166). New York, NY: Wiley.

Rothbaum, F., Weisz, J., Pott, M., Miyake, K., & Morelli, G. (2000). Attachment and culture: Security in the United States and Japan. American Psychologist, 55(10), 1093–1104.

Seifer, R., Schiller, M., Sameroff, A. J., Resnick, S., & Riordan, K. (1996). Attachment, maternal sensitivity, and infant temperament during the first year of life. Developmental Psychology, 32(1), 12–25.

Shrager, J., & Siegler, R. S. (1998). SCADS: A model of children’s strategy choices and strategy discoveries. Psychological Science, 9, 405–422.

Smith, L. B., & Thelen, E. (2003). Development as a dynamic system. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(8), 343–348.

Soska, K. C., Adolph, K. E., & Johnson, S. P. (2010). Systems in development: Motor skill acquisition facilitates three-dimensional object completion. Developmental Psychology, 46(1), 129–138.

thibs44. (2009, January 17). The strange situation – Mary Ainsworth [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QTsewNrHUHU

Thomas, A., & Chess, S. (1977). Temperament and development. New York, NY: Brunder/Mazel.

Thompson, R. A. (2012). Whither the preconventional child? Toward a life-span moral development theory. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 423–429.

Thompson, R. A. (2020). Social and personality development in childhood. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds.), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF. Retrieved from http://noba.to/gdqm6zvc

Thompson, R. A., Winer, A. C., & Goodvin, R. (2010). The individual child: Temperament, emotion, self, and personality. In M. Bornstein & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Developmental science: An advanced textbook (6th ed., pp. 423–464). New York, NY: Psychology Press/Taylor & Francis.

Tomasello, M. (1999). The cultural origins of human cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Trehub, S., & Rabinovitch, M. (1972). Auditory-linguistic sensitivity in early infancy. Developmental Psychology, 6(1), 74–77.

University of Montreal. (2010). Parenting style: Italians strict, French moderate, Canadians lenient. ScienceDaily. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/08/100830114946.htm

van den Boom, D. C. (1994). The influence of temperament and mothering on attachment and exploration: An experimental manipulation of sensitive responsiveness among lower-class mothers with irritable infants. Child Development, 65(5), 1457–1476.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wang, S. H., Baillargeon, R., & Brueckner, L. (2004). Young infants’ reasoning about hidden objects: Evidence from violation-of-expectation tasks with test trials only. Cognition, 93, 167–198.