10.5 Forgetting

Learning Objectives

- Describe Ebbinghaus’s forgetting curve.

- Describe processes that impede memory.

We’ve looked at how memories are made, so now we must turn to look more closely at forgetting. This section will cover some of the things that make it less likely for us to remember something. We’ll look at some of the processes that lead to forgetting.

In ordinary life, we do not remember everything we experience. As we discussed earlier, we simply do not encode a lot of what we experience, but what about memories that we do encode but later forget? Being able to forget is adaptive; if our consciousness was continually bombarded with memories, it would be difficult to cope with reality. What happens to the information that was encoded, stored, and then forgotten? Is it lost for all time? Many students will have had the experience of learning something thoroughly for a course, but then later on, perhaps only months later, be unable to remember more than a few facts. Let’s look at some of the processes that might be responsible for forgetting.

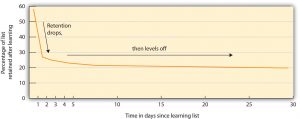

Probably the most intuitive way of understanding forgetting is the “use it or lose it” maxim: if we don’t think about something for a long time, then we tend to forget it eventually. Ebbinghaus’s forgetting curve is evidence in the short term of decay theory — the notion that memories decay (i.e., are forgotten) over time. Herman Ebbinghaus, the pioneering researcher of memory over 100 years ago whom we discovered earlier in this chapter, practised memorizing lists of nonsense syllables, such as the following:

- DIF, LAJ, LEQ, MUV, WYC, DAL, SEN, KEP, NUD

You can imagine that because the material that he was trying to learn was not at all meaningful, it was not easy to do. Ebbinghaus (1913) plotted how many of the syllables he could remember against the time that had elapsed since he had studied them. He discovered an important principle of memory: memory decays rapidly at first, but the degree of decay levels off with time (see Figure 10.13). Although Ebbinghaus looked at forgetting after days had elapsed, the same effect occurs on longer and shorter time scales. Harry Bahrick (1984) found that students who took a Spanish language course forgot about one half of the vocabulary that they had learned within three years, but after that time, their memory remained pretty much constant. Forgetting also drops off quickly on a shorter time frame. This suggests that you should try to review the material that you have already studied right before you take an exam; that way, you will be more likely to remember the material during the exam.

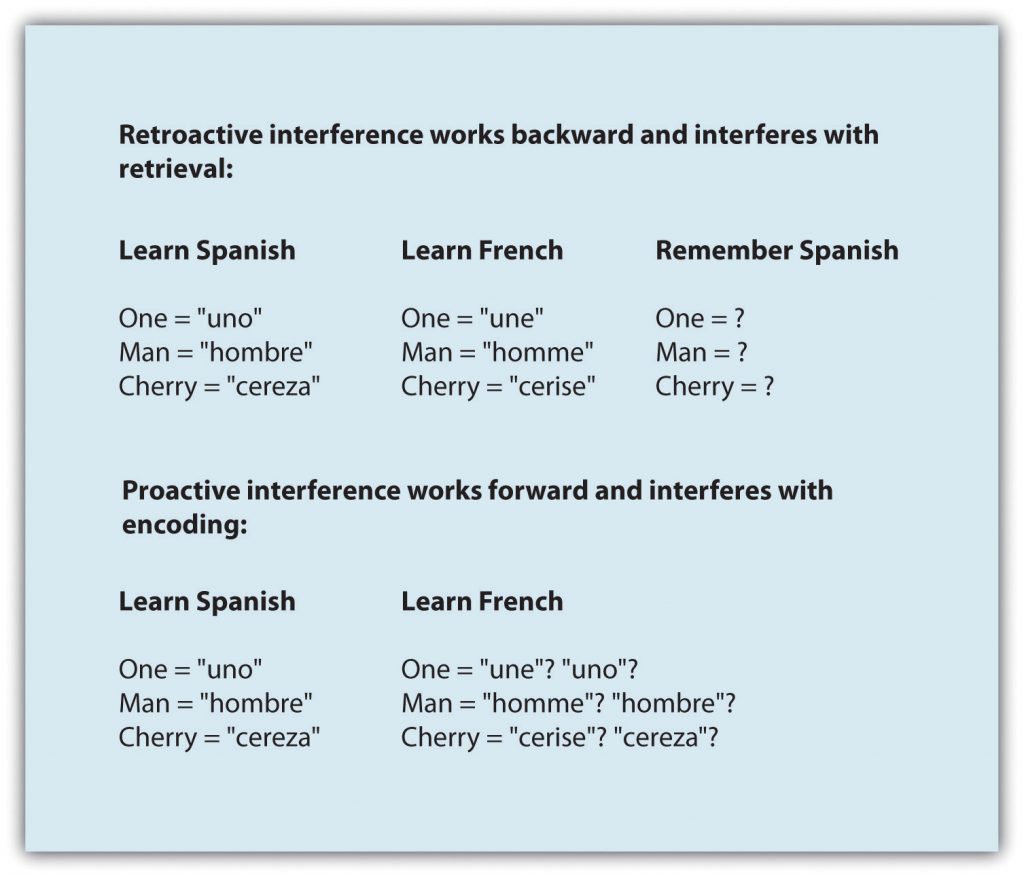

In some cases, our existing memories make it more likely that we will forget new information. This may occur either in a backward way or a forward way (see Figure 10.14). Retroactive interference occurs when learning something new impairs our ability to retrieve information that was learned earlier. For example, if you have learned to program in one computer language, and then you learn to program in another similar one, you may start to make mistakes programming the first language that you never would have made before you learned the new one. In this case, the new memories work backward (i.e., retroactively) to influence retrieval from memory that is already in place. We forget the old memories because the new ones have taken precedence. This is not simply a problem of encoding in the first place — the earlier memories were encoded and used, but then they were forgotten as they were interfered with by new information.

In contrast to retroactive interference, proactive interference works in a forward direction. Proactive interference occurs when earlier learning impairs our ability to encode information that we try to learn later. For example, if we have learned French as a second language, this knowledge may make it more difficult, at least in some respects, to learn a third language (e.g., Spanish), which involves similar but not identical vocabulary. In this case, we forget new information because the old memories have interfered.

Earlier, we discussed state-dependent learning; not surprisingly, this process works for forgetting as well. For example, when we are in a good mood, we tend to forget or ignore memories of things that are incongruent with happiness, and when we are unhappy, we tend to forget happy memories. These effects are called mood-congruent memory. This interplay of emotion and cognition is complex, but it may help to explain why some things are forgotten by some people but not others, or at certain times but not others. This congruence effect may broaden to other aspects of the situation; the less similar the recall context is to the context in which something was learned, the more we are likely to forget. Locations, times, people, facts, and pictures can all aid as memory cues to elicit memories that would otherwise be forgotten.

Most of us have some memories of our childhood. How far back can you remember? Researchers argue that anything learned before about age two is likely to be forgotten. This is called infantile amnesia (Newcombe, Lloyd, & Ratliff, 2007). Adults cannot remember being born, learning to talk, eating their first solid food, or learning to walk. These momentous events have been forgotten. Indeed, adult memories of the first few years of life seem to be largely forgotten, with most adults not being able to remember anything before ages three or four, until memory gradually increases for age seven and later (Bauer & Larkina, 2014).

Key Takeaways

- Ebbinghaus’s forgetting curve shows how information is forgotten over time.

- Retroactive and proactive interference both cause forgetting.

- Memories are affected by mood.

- Most adults cannot remember anything before ages three or four.

Image Attributions

Figure 10.13. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 10.14. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

Bahrick, H. P. (1984). Semantic memory content in permastore: Fifty years of memory for Spanish learned in school. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113(1), 1–29.

Bauer, P. J., & Larkina, M. (2014). Childhood amnesia in the making: Different distribution of autobiographical memories in children and adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology, General, 143(2), 597–611.

Ebbinghaus, H. (1913). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology (H. A. Ruger & C. E. Bussenius, Trans.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Newcombe, N. S., Lloyd, M. E., & Ratliff, K. R. (2007). Development of episodic and autobiographical memory: A cognitive neuroscience perspective. In R. V. Kail (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 35, pp. 37–85). San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press.