14.2 Personality as Traits

Learning Objectives

- Describe each of the Big Five personality traits and the low and high end of the dimension.

- Give examples of each of the Big Five personality traits, including both a low and high example.

- Describe other trait models of personality.

Personality traits reflect people’s characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. Personality traits imply consistency and stability; for example, someone who scores high on a specific trait like extraversion is expected to be sociable in different situations and over time. Thus, trait psychology rests on the idea that people differ from one another in terms of where they stand on a set of basic trait dimensions that persist over time and across situations. The most widely used system of traits is called the five-factor model. This system includes five broad traits that can be remembered with the acronym OCEAN: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Each of the major traits from the “Big Five” can be divided into facets to give a more fine-grained analysis of someone’s personality. In addition, some trait theorists argue that there are other traits that cannot be completely captured by the five-factor model. Critics of the trait concept argue that people do not act consistently from one situation to the next and that people are very influenced by situational forces. Thus, one major debate in the field concerns the relative power of people’s traits versus the situations in which they find themselves as predictors of their behaviour.

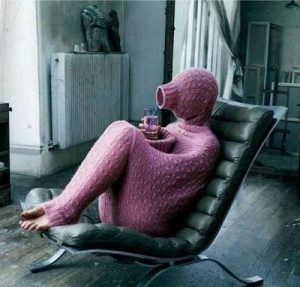

When we observe people around us, one of the first things that strikes us is how different people are from one another. Some people are very talkative, while others are very quiet. Some are active, whereas others are couch potatoes. Some worry a lot, others almost never seem anxious. Each time we use one of these words — words like “talkative,” “quiet,” “active,” or “anxious” — to describe those around us, we are talking about a person’s personality, that is, the characteristic ways that people differ from one another. Personality psychologists try to describe and understand these differences.

Although there are many ways to think about the personalities that people have, Gordon Allport and other “personologists” claimed that we can best understand the differences between individuals by understanding their personality traits. Personality traits reflect basic dimensions on which people differ (Matthews, Deary, & Whiteman, 2003). According to trait psychologists, there are a limited number of these dimensions — dimensions like extraversion, conscientiousness, or agreeableness — and each individual falls somewhere on each dimension, meaning that they could be low, medium, or high on any specific trait.

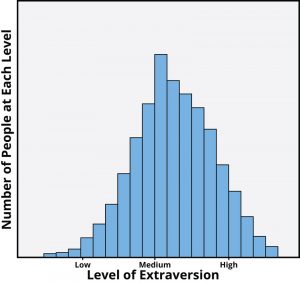

An important feature of personality traits is that they reflect continuous distributions rather than distinct personality types. This means that when personality psychologists talk about introverts and extraverts, they are not really talking about two distinct types of people who are completely and qualitatively different from one another. Instead, they are talking about people who score relatively low or relatively high along a continuous distribution. In fact, when personality psychologists measure traits like extraversion, they typically find that most people score somewhere in the middle, with smaller numbers showing more extreme levels. From a survey of thousands of people (see Figure 14.8), the distribution of extraversion scores indicates that most people report being moderately, but not extremely, extraverted, with fewer people reporting very high or very low scores.

There are three criteria that characterize personality traits: (1) consistency, (2) stability, and (3) individual differences.

- To have a personality trait, individuals must be somewhat consistent across situations in their behaviours related to the trait. For example, if they are talkative at home, they tend also to be talkative at work.

- Individuals with a trait are also somewhat stable over time in behaviours related to the trait. If they are talkative, for example, at age 30, they will also tend to be talkative at age 40.

- People differ from one another on behaviours related to the trait. Using speech is not a personality trait and neither is walking on two feet — virtually all individuals do these activities, and there are almost no individual differences. However, people differ on how frequently they talk and how active they are, and thus, personality traits such as “talkativeness” and “activity level” do exist.

A challenge of the trait approach was to discover the major traits on which all people differ. Scientists for many decades generated hundreds of new traits, so that it was soon difficult to keep track and make sense of them. For instance, one psychologist might focus on individual differences in “friendliness,” whereas another might focus on the highly related concept of “sociability.” Scientists began seeking ways to reduce the number of traits in some systematic way and to discover the basic traits that describe most of the differences between people.

The way that Gordon Allport and Henry Odbert approached this was to search the dictionary for all descriptors of personality (Allport & Odbert, 1936). Their approach was guided by the lexical hypothesis, which states that all important personality characteristics should be reflected in the language that we use to describe other people. Therefore, if we want to understand the fundamental ways in which people differ from one another, we can turn to the words that people use to describe one another. So, if we want to know what words people use to describe one another, where should we look? Allport and Odbert looked in the most obvious place: the dictionary. Specifically, they took all the personality descriptors that they could find in the dictionary; they started with almost 18,000 words but quickly reduced that list to a more manageable number. Then, they used statistical techniques to determine which words went together. In other words, if everyone who said that they were “friendly” also said that they were “sociable,” then this might mean that personality psychologists would only need a single trait to capture individual differences in these characteristics. Statistical techniques were used to determine whether a small number of dimensions might underlie all of the thousands of words we use to describe people.

The five-factor model of personality

Research that used the lexical approach showed that many of the personality descriptors found in the dictionary do indeed overlap. That is to say, many of the words that we use to describe people are synonyms. Thus, if we want to know what a person is like, we do not necessarily need to ask how sociable they are, how friendly they are, and how gregarious they are. Instead, because sociable people tend to be friendly and gregarious, we can summarize this personality dimension with a single term. Someone who is sociable, friendly, and gregarious would typically be described as an “extravert.” Once we know they are an extravert, we can assume that they are sociable, friendly, and gregarious.

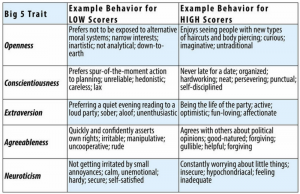

Statistical methods — specifically, a technique called factor analysis — helped to determine whether a small number of dimensions underlie the diversity of words that people like Allport and Odbert identified. The most widely accepted system to emerge from this approach was the Big Five, or five-factor model (Goldberg, 1990; McCrae & John, 1992; McCrae & Costa, 1987). The Big Five comprises five major traits (see Figure 14.9). A way to remember these five is with the acronym OCEAN, which stands for openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Consider the descriptions of people who would score high and low on each of these traits (see Figure 14.10).

Scores on the Big Five traits are mostly independent. That means that a person’s standing on one trait tells very little about their standing on the other traits of the Big Five. For example, a person can be extremely high in extraversion and be either high or low on neuroticism. Similarly, a person can be low in agreeableness and be either high or low in conscientiousness. Thus, in the five-factor model, you need five scores to describe most of an individual’s personality.

At the end of this section, a short scale is presented to assess the five-factor model of personality (Donnellan, Oswald, Baird, & Lucas, 2006). You can take this test to see where you stand in terms of your Big Five scores. John Johnson (n.d.) has also created a “Short Form for the IPIP-NEO” with personality scales that can be used and taken by the general public. After seeing your scores, you can judge for yourself whether you think such tests are valid.

Traits are important and interesting because they describe stable patterns of behaviour that persist for long periods of time (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005). Importantly, these stable patterns can have broad-ranging consequences for many areas of our life (Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, 2007). For instance, think about the factors that determine success in college. If you were asked to guess what factors predict good grades in college, you might guess something like intelligence. This guess would be correct, but we know much more about who is likely to do well. Specifically, personality researchers have also found the personality traits like “conscientiousness” play an important role in college and beyond, probably because highly conscientious individuals study hard, get their work done on time, and are less distracted by nonessential activities that take time away from school work. In addition, highly conscientious people are often healthier than people low in conscientiousness because they are more likely to maintain healthy diets, to exercise, and to follow basic safety procedures like wearing seat belts or bicycle helmets. Over the long term, this consistent pattern of behaviours can add up to meaningful differences in health and longevity. Thus, personality traits are not just a useful way to describe people you know; they actually help psychologists predict how good a worker someone will be, how long they will live, and the types of jobs and activities the person will enjoy. Thus, there is growing interest in personality psychology among psychologists who work in applied settings, such as health psychology or organizational psychology.

Facets of traits (subtraits)

So, how does it feel to be told that your entire personality can be summarized with scores on just five personality traits? Do you think these five scores capture the complexity of your own and others’ characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours? Most people would probably say no, pointing to some exception in their behaviour that goes against the general pattern that others might see. For instance, you may know people who are warm and friendly and find it easy to talk with strangers at a party, yet they are terrified if they have to perform in front of others or speak to large groups of people. The fact that there are different ways of being extraverted or conscientious shows that there is value in considering lower-level units of personality that are more specific than the Big Five traits. These more specific, lower-level units of personality are often called facets.

It is important to note that although personality researchers generally agree about the value of the Big Five traits as a way to summarize one’s personality, there is no widely accepted list of facets that should be studied. The work by researchers Jeff McCrae and Paul Costa (1987) thus reflects just one possible list among many (see Figure 14.11). It should, however, give you an idea of some of the facets making up each of the five-factor model.

Facets can be useful because they provide more specific descriptions of what a person is like. For instance, if we take our friend who loves parties but hates public speaking, we might say that this person scores high on the “gregariousness” and “warmth” facets of extraversion, while scoring lower on facets such as “assertiveness” or “excitement-seeking.” This precise profile of facet scores not only provides a better description, it might also allow us to better predict how this friend will do in a variety of different jobs, such as jobs that require public speaking versus jobs that involve one-on-one interactions with customers (Paunonen & Ashton, 2001). Because different facets within a broad, global trait like extraversion tend to go together (e.g., those who are gregarious are often, but not always, assertive), the broad trait often provides a useful summary of what a person is like, but when we really want to know a person, facet scores add to our knowledge in important ways.

Other traits beyond the five-factor model

Despite the popularity of the five-factor model, it is certainly not the only model that exists. Some suggest that there are more than five major traits or perhaps even fewer. For example, in one of the first comprehensive models to be proposed, Hans Eysenck suggested that extraversion and neuroticism are most important. Eysenck believed that by combining people’s standing on these two major traits, we could account for many of the differences in personality that we see in people (Eysenck, 1981). So, for instance, a neurotic introvert would be shy and nervous, while a stable introvert might avoid social situations and prefer solitary activities but may do so with a calm, steady attitude and little anxiety or emotion. Interestingly, Eysenck attempted to link these two major dimensions to underlying differences in people’s biology. For instance, he suggested that introverts experienced too much sensory stimulation and arousal, which made them want to seek out quiet settings and less stimulating environments. More recently, Jeffrey Gray suggested that these two broad traits are related to fundamental reward and avoidance systems in the brain. Extraverts might be motivated to seek reward, and thus exhibit assertive, reward-seeking behaviour, whereas people high in neuroticism might be motivated to avoid punishment, and thus may experience anxiety as a result of their heightened awareness of the threats in the world around them (Gray, 1981). This model has since been updated (Gray & McNaughton, 2000). These early theories have led to a burgeoning interest in identifying the physiological underpinnings of the individual differences that we observe.

Another revision of the Big Five is the HEXACO model of traits (Ashton & Lee, 2007). This model is similar to the Big Five, but it posits slightly different versions of some of the traits, and its proponents argue that one important class of individual differences was omitted from the five-factor model. The HEXACO adds honesty-humility as a sixth dimension of personality. People high in this trait are sincere, fair, and modest, whereas those low in the trait are manipulative, narcissistic, and self-centred. Thus, trait theorists are agreed that personality traits are important in understanding behaviour, but there are still debates on the exact number and composition of the traits that are most important.

There are other important traits that are not included in comprehensive models like the Big Five. Although the five factors capture much that is important about personality, researchers have suggested other traits that capture interesting aspects of our behaviour. Refer to the few, out of hundreds, of the other traits that have been studied by personologists (see Figure 14.12).

Not all of the above traits are currently popular with scientists, yet each of them has experienced popularity in the past. Although the five-factor model has been the target of more rigorous research than some of the traits above, these additional personality characteristics give a good idea of the wide range of behaviours and attitudes that traits can cover.

The mini-IPIP scale

Below are phrases describing people’s behaviours. Use the rating scale below to describe how accurately each statement describes you. Describe yourself as you generally are now, not as you wish to be in the future. Describe yourself as you honestly see yourself, in relation to other people you know of the same sex and roughly your same age. Read each statement carefully, and put a number from 1 to 5 next to it to describe how accurately the statement describes you.

- 1 = Very inaccurate

- 2 = Moderately inaccurate

- 3 = Neither inaccurate nor accurate

- 4 = Moderately accurate

- 5 = Very accurate

- _______ Am the life of the party (E)

- _______ Sympathize with others’ feelings (A)

- _______ Get chores done right away (C)

- _______ Have frequent mood swings (N)

- _______ Have a vivid imagination (O)

- _______Don’t talk a lot (E)

- _______ Am not interested in other people’s problems (A)

- _______ Often forget to put things back in their proper place (C)

- _______ Am relaxed most of the time (N)

- _______ Am not interested in abstract ideas (O)

- _______ Talk to a lot of different people at parties (E)

- _______ Feel others’ emotions (A)

- _______ Like order (C)

- _______ Get upset easily (N)

- _______ Have difficulty understanding abstract ideas (O)

- _______ Keep in the background (E)

- _______ Am not really interested in others (A)

- _______ Make a mess of things (C)

- _______ Seldom feel blue (N)

- _______ Do not have a good imagination (O)

In terms of scoring, the first thing you must do is to reverse the items that are worded in the opposite direction. In order to do this, subtract the number you put for that item from 6. So, if you put a 4, for instance, it will become a 2. Cross out the score you put when you took the scale, and put the new number in representing your score subtracted from the number 6.

Items to be reversed in this way: 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

Next, you need to add up the scores for each of the five OCEAN scales, including the reversed numbers where relevant. Each OCEAN score will be the sum of four items. Place the sum next to each scale below.

__________ Openness: Add items 5, 10, 15, 20

__________ Conscientiousness: Add items 3, 8, 13, 18

__________ Extraversion: Add items 1, 6, 11, 16

__________ Agreeableness: Add items 2, 7, 12, 17

__________ Neuroticism: Add items 4, 9,14, 19

Compare your scores to the norms below to see where you stand on each scale. If you are low on a trait, it means you are the opposite of the trait label. For example, low on extraversion is introversion, low on openness is conventional, and low on agreeableness is assertive.

19–20 Extremely High, 17–18 Very High, 14–16 High, 11–13 Neither high nor low, 8–10 Low, 6–7 Very low, 4–5 Extremely low

(Donnellan, Oswald, Baird, & Lucas, 2006)

Additional resources

The following YouTube link shows Gabriela Cintron’s student-made video, which cleverly describes common behavioural characteristics of the Big Five personality traits through song:

- Video: 5 Factors of Personality – OCEAN Song (Nguyen, 2017)

The following Vimeo link shows Michael Harris’s student-made video that looks at characteristics of the OCEAN traits through a series of funny vignettes and presents on the Person vs. Situation debate:

- Video: Personality Traits – The Big 5 and More (Harris, n.d.)

The following YouTube link shows David M. Cole’s student-made video about the relationship between personality traits and behaviour using a handy weather analogy:

- Video: Grouchy With a Chance of Stomping (ObserveChange.org, 2017)

Source: Adapted from Diener and Lucas (2020).

Psychology in Everyday Life

Leaders and leadership

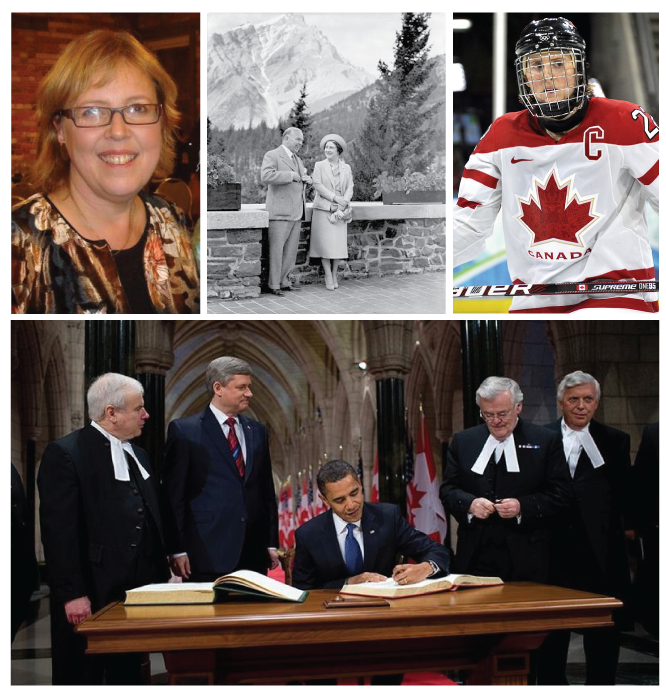

One trait that has been studied in thousands of studies is leadership, which is the ability to direct or inspire others to achieve goals. Trait theories of leadership are theories based on the idea that some people are simply “natural leaders” because they possess personality characteristics that make them effective (Zaccaro, 2007). Consider Elizabeth May, the leader of the Green Party of Canada (see Figure 14.13). What characteristics do you think she possessed that allowed her to function as the sole member of her party in Parliament when she was first elected?

Research has found that being intelligent is an important characteristic of leaders, as long as the leader communicates to others in a way that is easily understood by their followers (Simonton, 1994, 1995). Other research has found that people with good social skills, such as the ability to accurately perceive the needs and goals of the group members and communicate with others, also tend to make good leaders (Kenny & Zaccaro, 1983). Because so many characteristics seem to be related to leaderhip skills, some researchers have attempted to account for leadership not in terms of individual traits, but rather in terms of a package of traits that successful leaders seem to have. Some have considered this in terms of charisma (Sternberg & Lubart, 1995; Sternberg, 2002). Charismatic leaders are leaders who are enthusiastic, committed, and self-confident; who tend to talk about the importance of group goals at a broad level; and who make personal sacrifices for the group. Charismatic leaders express views that support and validate existing group norms but that also contain a vision of what the group could or should be. Charismatic leaders use their referent power to motivate, uplift, and inspire others. Additionally, research has found a positive relationship between a leader’s charisma and effective leadership performance (Simonton, 1988).

Another trait-based approach to leadership is based on the idea that leaders take either transactional or transformational leadership styles with their subordinates (Bass, 1999; Pieterse, van Knippenberg, Schippers, & Stam, 2010). Transactional leaders are the more regular leaders, who work with their subordinates to help them understand what is required of them and to get the job done. Transformational leaders, on the other hand, are more like charismatic leaders — they have a vision of where the group is going and attempt to stimulate and inspire their followers to move beyond their present status and create a new and better future.

Despite the fact that there appear to be at least some personality traits that relate to leadership ability, the most important approaches to understanding leadership take into consideration both the personality characteristics of the leader as well as the situation in which the leader is operating. In some cases, the situation itself is important. For instance, during the Calgary flooding of 2013, Mayor Naheed Nenshi enhanced his popularity further with his ability to support and unify the community, thereby ensuring that the Calgary Stampede went ahead as planned despite severe damage to the fair grounds and arenas. In still other cases, different types of leaders may perform differently in different situations. Leaders whose personalities lead them to be more focused on fostering harmonious social relationships among the members of the group, for instance, are particularly effective in situations in which the group is already functioning well, and yet it is important to keep the group members engaged in the task and committed to the group outcomes. Leaders who are more task-oriented and directive, on the other hand, are more effective when the group is not functioning well and needs a firm hand for guidance (Ayman, Chemers, & Fiedler, 1995).

Key Takeaways

- Personality is driven in large part by underlying individual motivations, where motivation refers to a need or desire that directs behaviour.

- Personalities are characterized in terms of traits — relatively enduring characteristics that influence our behaviour across many situations.

- The most important and well-validated theory about the traits of normal personality is the five-factor model of personality.

- There is often a low correlation between the specific traits that a person expresses in one situation and those that they expresses in other situations.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Consider your own personality and those of people you know. What traits do you enjoy in other people, and what traits do you dislike?

- Consider some of the people who have had an important influence on you. What were the personality characteristics of these people that made them so influential?

- Consider different combinations of the Big Five, such as O (Low), C (High), E (Low), A (High), and N (Low). What would this person be like? Do you know anyone who is like this? Can you select politicians, movie stars, and other famous people and rate them on the Big Five?

Image Attributions

Figure 14.7. Fwd: How Not to Manage an Introvert? by Nguyen Hung Vu is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 14.8. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 14.9. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 14.10. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 14.11. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 14.12. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 14.13. Elizabeth May and Emma Hogbin by Emma Jane Hogbin Westby is used under a CC BY 2.0 license; QueenMotherandWLMK by National Film Board of Canada is in the public domain; Hayley Wickenheiser at 2010 Olympics by VancityAllie.com is used under a CC BY 2.0 license; Barack Obama Signs Parliament of Canada Guestbook 2-19-09 by Pete Souza is in the public domain.

Long Descriptions

Figure 14.13. Leader of the Green Party of Canada, Elizabeth May (top left); Queen Mother with Prime Minister William Lyon MacKenzie King (top middle); Hayley Wikenheiser, Captain of Canadian Women’s National Hockey team (top right); Prime Minister Stephen Harper and President Barack Obama signing Canadian Parliamentary guestbook (bottom).

References

Allport, G. W., & Odbert, H. S. (1936). Trait names: A psycholexical study. Psychological Monographs, 47, 211.

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2007). Empirical, theoretical, and practical advantages of the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personality and Social Psychological Review, 11, 150–166.

Ayman, R., Chemers, M. M., & Fiedler, F. (1995). The contingency model of leadership effectiveness: Its level of analysis. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 147–167.

Bass, B. M. (1999). Current developments in transformational leadership: Research and applications. Psychologist-Manager Journal, 3(1), 5–21.

Caspi, A., Roberts, B. W., & Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Reviews of Psychology, 56, 453–484.

Diener, E., & Lucas, R. E. (2020). Personality traits. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds.), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF. Retrieved from http://noba.to/96u8ecgw

Donnellan, M. B., Oswald, F. L., Baird, B. M., & Lucas, R. E. (2006). The mini-IPIP scales: Tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five factors of personality. Psychological Assessment, 18, 192–203.

Eysenck, H. J. (1981). A model for personality. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative description of personality: The Big Five personality traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1216–1229.

Gray, J. A. (1981). A critique of Eysenck’s theory of personality. In H. J. Eysenck (Ed.), A model for personality (pp. 246–276). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Gray, J. A., & McNaughton, N. (2000). The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system (2nd ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Harris, M. (n.d.). Personality traits – The Big 5 and more [Video file]. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/user4722143

Johnson, J. (n.d.) Short form for the IPIP-NEO. Retrieved from http://www.personal.psu.edu/j5j/IPIP/ipipneo120.htm

Kenny, D. A., & Zaccaro, S. J. (1983). An estimate of variance due to traits in leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68(4), 678–685.

Matthews, G., Deary, I. J., & Whiteman, M. C. (2003). Personality traits. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52(1), 81–90.

McCrae, R. R., & John, O. P. (1992). An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality, 60, 175–215.

Nguyen, V. (2017, May 19). 5 Factors of personality – OCEAN song [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rk8CDXMb8_U&feature=emb_title

ObserveChange.org. (2017, May 15). Grouchy with a chance of stomping [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GnaFMjaJtlY&feature=emb_title

Paunonen, S. V., & Ashton, M. S. (2001). Big Five factors and facets and the prediction of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 524–539.

Pieterse, A. N., van Knippenberg, D., Schippers, M., & Stam, D. A. (2010). Transformational and transactional leadership and innovative behavior: The moderating role of psychological empowerment. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(4), 609–623.

Roberts, B. W., Kuncel, N. R., Shiner, R., Caspi, A., & Goldberg, L. R. (2007). The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2(4), 313–345.

Simonton, D. K. (1988). Presidential style: Personality, biography, and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55, 928–936.

Simonton, D. K. (1994). Greatness: Who makes history and why. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Simonton, D. K. (1995). Personality and intellectual predictors of leadership. In D. H. Saklofske & M. Zeidner (Eds.), International handbook of personality and intelligence: Perspectives on individual differences (pp. 739–757). New York, NY: Plenum.

Sternberg, R. J. (2002). Successful intelligence: A new approach to leadership. In R. E. Riggio, S. E. Murphy, & F. J. Pirozzolo (Eds.), Multiple intelligences and leadership (pp. 9–28). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Sternberg, R. J., & Lubart, T. I. (1995). Defying the crowd: Cultivating creativity in a culture of conformity. New York, NY: Free Press.

Zaccaro, S. J. (2007). Trait-based perspectives of leadership. American Psychologist, 62(1), 6–16.