13.6 Late Adulthood: Aging, Retiring, and Bereavement

Learning Objectives

- Explain research approaches to studying aging.

- Describe cognitive, psychosocial, and physical changes that occur with age.

- Provide examples of how age-related changes in these domains are observed in the context of everyday life.

- Describe the psychological and physical outcomes of bereavement.

We are currently living in an aging society (Rowe, 2009). Indeed, by 2030, when the last of the Baby Boomers reach age 65, the older population in Canada and the United States will be double that of 2010. Furthermore, because of increases in average life expectancy, each new generation can expect to live longer than their parents’ generation and certainly longer than their grandparents’ generation. As a consequence, it is time for individuals of all ages to rethink their personal life plans and consider prospects for a long life. When is the best time to start a family? Will the education gained up to age 20 be sufficient to cope with future technological advances and marketplace needs? What is the right balance between work, family, and leisure throughout life? What’s the best age to retire? How can someone age successfully and enjoy life to the fullest at 80 or 90 years old? In this section, we will discuss several different domains of psychological research on aging that will help answer these important questions.

Life span and life course perspectives on aging

Just as young adults differ from one another, older adults are also not all the same. In each decade of adulthood, we observe substantial heterogeneity in cognitive functioning, personality, social relationships, lifestyle, beliefs, and satisfaction with life. This heterogeneity reflects differences in rates of biogenetic and psychological aging and the sociocultural contexts and history of people’s lives (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Fingerman, Berg, Smith, & Antonucci, 2011). Theories of aging describe how these multiple factors interact and change over time. They describe why functioning differs on average between young, middle-aged, old, and very old adults and why there is heterogeneity within these age groups. Life course theories, for example, highlight the effects of social expectations and the normative timing of life events and social roles, such as becoming a parent or experiencing retirement. They also consider the lifelong cumulative effects of membership in specific cohorts (i.e., generations), sociocultural subgroups such as race, gender, or socioeconomic status, and exposure to historical events such as war, revolution, or natural disasters (Elder, Johnson, & Crosnoe, 2003; Settersten, 2005). Life span theories complement the life-course perspective with a greater focus on processes within the individual (e.g., the aging brain). This approach emphasizes the patterning of lifelong intra- and inter-individual differences in the shape, level, and rate of change (Baltes, 1987; Baltes & Lindenberger, 1997). Both life course and life span researchers generally rely on longitudinal studies to examine hypotheses about different patterns of aging associated with the effects of biogenetic, life history, social, and personal factors. Cross-sectional studies provide information about age-group differences, but these are confounded with cohort, time of study, and historical effects.

Cognitive aging

Researchers have identified areas of both losses and gains in cognition in older age. Cognitive ability and intelligence are often measured using standardized tests and validated measures. The psychometric approach has identified two categories of intelligence that show different rates of change across the life span (Schaie & Willis, 1996). Fluid intelligence refers to information processing abilities, such as logical reasoning, remembering lists, spatial ability, and reaction time. Crystallized intelligence encompasses abilities that draw upon experience and knowledge. Measures of crystallized intelligence include vocabulary tests, solving number problems, and understanding texts.

Older adults have more crystallized intelligence — that is, general knowledge about the world, as reflected in semantic knowledge, vocabulary, and language. As a result, adults generally outperform younger people on measures of history, geography, and even on crossword puzzles, where this information is useful (Salthouse, 2004). It is this superior knowledge, combined with a slower and more complete processing style, along with a more sophisticated understanding of the workings of the world around them, that gives the elderly the advantage of wisdom over the advantages of fluid intelligence — the ability to think and acquire information quickly and abstractly — which favour the young (Baltes, Staudinger, & Lindenberger, 1999; Scheibe, Kunzmann, & Baltes, 2009).

The differential changes in crystallized versus fluid intelligence help explain why the elderly do not necessarily show poorer performance on tasks that also require experience (i.e., crystallized intelligence), although they show poorer memory overall. A young chess player may think more quickly, for instance, but a more experienced chess player has more knowledge to draw on. Older adults are also more effective at understanding the nuances of social interactions than younger adults are, in part because they have more experience in relationships (Blanchard-Fields, Mienaltowski, & Seay, 2007).

Whereas it was once believed that almost all older adults suffered from a generalized memory loss, research now indicates that healthy older adults actually experience only some particular types of memory deficits, while other types of memory remain relatively intact or may even improve with age. Older adults do seem to process information more slowly — it may take them longer to evaluate information and to understand language, and it takes them longer, on average, than it does younger people, to recall a word that they know, even though they are perfectly able to recognize the word once they see it (Burke, Shafto, Craik, & Salthouse, 2008). Older adults also have more difficulty inhibiting and controlling their attention (Persad, Abeles, Zacks, & Denburg, 2002), making them, for example, more likely to talk about topics that are not relevant to the topic at hand when conversing (Pushkar et al., 2000).

With age, systematic declines are observed on cognitive tasks requiring self-initiated, effortful processing, without the aid of supportive memory cues (Park, 2000). Older adults tend to perform poorer than young adults on memory tasks that involve recall of information, where individuals must retrieve information they learned previously without the help of a list of possible choices. For example, older adults may have more difficulty recalling facts such as names or contextual details about where or when something happened (Craik, 2000). What might explain these deficits as we age? As we age, working memory, which is our ability to simultaneously store and use information, becomes less efficient (Craik & Bialystok, 2006). The ability to process information quickly also decreases with age. This slowing of processing speed may explain age differences on many different cognitive tasks (Salthouse, 2004). Some researchers have argued that inhibitory functioning, which is the ability to focus on certain information while suppressing attention to less pertinent information, declines with age and may explain age differences in performance on cognitive tasks (Hasher & Zacks, 1988). Finally, it is well established that our hearing and vision decline as we age. Longitudinal research has proposed that deficits in sensory functioning explain age differences in a variety of cognitive abilities (Baltes & Lindenberger, 1997).

Fewer age differences are observed when memory cues are available, such as for recognition memory tasks, when individuals can draw upon acquired knowledge or experience. For example, older adults often perform as well if not better than young adults on tests of word knowledge or vocabulary. With age often comes expertise, and research has pointed to areas where aging experts perform as well or better than younger individuals. For example, older typists were found to compensate for age-related declines in speed by looking farther ahead at printed text (Salthouse, 1984). Compared to younger players, older chess experts are able to focus on a smaller set of possible moves, leading to greater cognitive efficiency (Charness, 1981). Accrued knowledge of everyday tasks, such as grocery prices, can help older adults to make better decisions than young adults (Tentori, Osheron, Hasher, & May, 2001).

How do changes or maintenance of cognitive ability affect older adults’ everyday lives? Researchers have studied cognition in the context of several different everyday activities. One example is driving. Although older adults often have more years of driving experience, cognitive declines related to reaction time, known as attentional processes, may pose limitations under certain circumstances (Park & Gutchess, 2000). Research on interpersonal problem solving suggested that older adults use more effective strategies than younger adults to navigate through social and emotional problems (Blanchard-Fields, 2007). In the context of work, researchers rarely find that older individuals perform poorer on the job (Park & Gutchess, 2000). Similar to everyday problem solving, older workers may develop more efficient strategies and rely on expertise to compensate for cognitive decline.

Personality and self-related processes

Research on adult personality examines normative age-related increases and decreases in the expression of the so-called “Big Five” traits: extraversion, neuroticism, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness to new experience. Does personality change throughout adulthood? Previously the answer was no, but contemporary research shows that although some people’s personalities are relatively stable over time, others’ are not (Lucas & Donnellan, 2011; Roberts & Mroczek, 2008). Longitudinal studies reveal average changes during adulthood in the expression of some traits (e.g., neuroticism and openness decrease with age and conscientiousness increases) and individual differences in these patterns due to idiosyncratic life events (e.g., divorce or illness). Longitudinal research also suggests that adult personality traits, such as conscientiousness, predict important life outcomes including job success, health, and longevity (Friedman et al., 1993; Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, 2007).

In contrast to the relative stability of personality traits, theories about the aging self-propose changes in self-related knowledge, beliefs, and autobiographical narratives. Responses to questions such as “Who are you?” and “What are your hopes for the future?” provide insight into the characteristics and life themes that an individual considers uniquely distinguishable about themself. These self-descriptions enhance self-esteem and guide behaviour (Markus & Nurius, 1986; McAdams, 2006). Theory suggests that as we age, themes that were relatively unimportant in young and middle adulthood gain in salience (e.g., generativity and health) and that people view themselves as improving over time (Ross & Wilson, 2003). Reorganizing personal life narratives and self-descriptions are the major tasks of midlife and late adulthood due to transformations in professional and family roles and obligations. In advanced old age, self-descriptions are often characterized by a life review and reflections about having lived a long life. James Birren and Johannes Schroots (2006), for example, found the process of life review in late life helped individuals confront and cope with the challenges of old age.

One aspect of the self that particularly interests life span and life course psychologists is the individual’s perception and evaluation of their own aging and identification with an age group. Subjective age is a multidimensional construct that indicates how old, or young, a person feels and into which age group a person categorizes themself. After early adulthood, most people say that they feel younger than their chronological age, and the gap between subjective age and actual age generally increases. On average, after age 40, people report feeling 20% younger than their actual age (e.g., Rubin & Berntsen, 2006). Asking people how satisfied they are with their own aging assesses an evaluative component of age identity. Whereas some aspects of age identity are positively valued (e.g., acquiring seniority in a profession or becoming a grandparent), others may be less valued, depending on societal context. Perceived physical age (i.e., the age one looks in a mirror) is one aspect that requires considerable self-related adaptation in social and cultural contexts that value young bodies. Feeling younger and being satisfied with one’s own aging are expressions of positive self-perceptions of aging. They reflect the operation of self-related processes that enhance wellbeing. Becca Levy (2009) found that older individuals who are able to adapt to and accept changes in their appearance and physical capacity in a positive way report higher wellbeing, have better health, and live longer.

Social relationships

Social ties to family, friends, mentors, and peers are primary resources of information, support, and comfort. Individuals develop and age together with family and friends and interact with others in the community. Across the life course, social ties are accumulated, lost, and transformed. Already in early life, there are multiple sources of heterogeneity in the characteristics of each person’s social network of relationships (e.g., size, composition, and quality). Life course and life span theories, as well as research about age-related patterns in social relationships, focus on understanding changes in the processes underlying social connections. Toni Antonucci’s convoy model of social relations (2001; Kahn & Antonucci, 1980), for example, suggests that the social connections that people accumulate are held together by exchanges in social support (e.g., tangible and emotional). The frequency, types, and reciprocity of the exchanges change with age and in response to need, and in turn, these exchanges impact the health and wellbeing of the givers and receivers in the convoy. In many relationships, it is not the actual objective exchange of support that is critical, but instead it is the perception that support is available if needed (Uchino, 2009). Laura Carstensen’s socioemotional selectivity theory (1993; Carstensen, Isaacowitz, & Charles, 1999) focuses on changes in motivation for actively seeking social contact with others. Carstensen proposes that with increasing age our motivational goals change from information gathering to emotion regulation. To optimize the experience of positive affect, older adults actively restrict their social life to prioritize time spent with emotionally close significant others. In line with this, older marriages are found to be characterized by enhanced positive and reduced negative interactions, and older partners show more affectionate behaviour during conflict discussions than do middle-aged partners (Carstensen, Gottman, & Levenson, 1995). Research showing that older adults tend to avoid negative interactions and have smaller networks compared to young adults also supports this theory. Similar selective processes are also observed when time horizons for interactions with close partners shrink temporarily for young adults (e.g., impending geographical separations).

Much research focuses on the associations between specific effects of long-term social relationships and health in later life. Older married individuals who receive positive social and emotional support from their partner generally report better health than their unmarried peers (Antonucci, 2001; Umberson, Williams, Powers, Liu, & Needham, 2006; Waite & Gallagher, 2000). Despite the overall positive health effects of being married in old age — compared with being widowed, divorced, or single — living as a couple can have a “dark side” if the relationship is strained or if one partner is the primary caregiver. The consequences of positive and negative aspects of relationships are complex (Birditt & Antonucci, 2008; Rook, 1998; Uchino, 2009). For example, in some circumstances, criticism from a partner may be perceived as valid and useful feedback whereas in others it is considered unwarranted and hurtful. In long-term relationships, habitual negative exchanges might have diminished effects. Parent-child and sibling relationships are often the most long-term and emotion-laden social ties. Across the life span, the parent-child tie, for example, is characterized by a paradox of solidarity, conflict, and ambivalence (Fingerman, Chen, Hay, Cichy, & Lefkowitz, 2006).

Emotion and wellbeing

As we get older, the likelihood of losing loved ones or experiencing declines in health increases. Does the experience of such losses result in decreases in wellbeing in older adulthood? Researchers have found that wellbeing differs across the life span and that the patterns of these differences depend on how wellbeing is measured.

Measures of global subjective wellbeing assess individuals’ overall perceptions of their lives. This can include questions about life satisfaction or judgments of whether individuals are currently living the best life possible. What factors may contribute to how people respond to these questions? Age, health, personality, social support, and life experiences have been shown to influence judgments of global wellbeing. It is important to note that predictors of wellbeing may change as we age. What is important to life satisfaction in young adulthood can be different in later adulthood (George, 2010). Early research on wellbeing argued that life events such as marriage or divorce can temporarily influence wellbeing, but people quickly adapt and return to a neutral baseline, called the hedonic treadmill (Diener, Lucas, & Scollon, 2006). More recent research suggests otherwise. Using longitudinal data, researchers have examined wellbeing prior to, during, and after major life events such as widowhood, marriage, and unemployment (Lucas, 2007). Different life events influence wellbeing in different ways, and individuals do not often adapt back to baseline levels of wellbeing. The influence of events, such as unemployment, may have a lasting negative influence on wellbeing as people age. Research suggests that global wellbeing is highest in early and later adulthood and lowest in midlife (Stone, Schwartz, Broderick, & Deaton, 2010).

Hedonic wellbeing refers to the emotional component of wellbeing and includes measures of positive affect (e.g., happiness and contentment) and negative affect (e.g., stress and sadness). The pattern of positive affect across the adult life span is similar to that of global wellbeing, with experiences of positive emotions such as happiness and enjoyment being highest in young and older adulthood. Experiences of negative affect, particularly stress and anger, tend to decrease with age. Experiences of sadness are lowest in early and later adulthood compared to midlife (Stone et al., 2010). Other research finds that older adults report more positive and less negative affect than middle age and younger adults (Magai, 2008; Mroczek, 2001). It should be noted that both global wellbeing and positive affect tend to taper off during older adulthood, and these declines may be accounted for by increases in health-related losses during these years (Charles & Carstensen, 2010).

Psychological wellbeing aims to evaluate the positive aspects of psychosocial development, as opposed to factors of ill-being, such as depression or anxiety. Carol Ryff’s model of psychological wellbeing proposes six core dimensions of positive wellbeing. Older adults tend to report higher environmental mastery (e.g., feelings of competence and control in managing everyday life) and autonomy (e.g., a sense of independence), lower personal growth and purpose in life, and similar levels of positive relations with others as younger individuals (Ryff, 1995). Links between health and interpersonal flourishing, or having high-quality connections with others, may be important in understanding how to optimize quality of life in old age (Ryff & Singer, 2000).

Social changes during aging: Retiring effectively

Because of increased life expectancy in the 21st century, elderly people can expect to spend approximately a quarter of their lives in retirement. Leaving one’s career is a major life change and can be a time when people experience anxiety, depression, and other negative changes in conceptions of self and in self-identity. On the other hand, retirement may also serve as an opportunity for a positive transition from work and career roles to stronger family and community member roles, and the latter may have a variety of positive outcomes for the individual. Retirement may be a relief for people who have worked in boring or physically demanding jobs, particularly if they have other outlets for stimulation and expressing self-identity.

Psychologist Mo Wang (2007) observed the wellbeing of 2,060 people between the ages of 51 and 61 over an eight-year period and made the following recommendations to make the retirement phase a positive one:

- Work part time — Continue to work part-time past retirement in order to ease into retirement status slowly.

- Plan for retirement — This is a good idea financially, but also making plans to incorporate other kinds of work or hobbies into post-employment life makes sense.

- Retire with someone — If the retiree is still married, it is a good idea to retire at the same time as a spouse so that people can continue to work part-time and follow a retirement plan together.

- Have a happy marriage — People with marital problems tend to find retirement more stressful because they do not have a positive home life to return to and can no longer seek refuge in long working hours. Couples that work on their marriages can make their retirements a lot easier.

- Take care of physical and financial health — A sound financial plan and good physical health can ensure a healthy, peaceful retirement.

- Retire early from a stressful job — People who stay in stressful jobs for fear that they will lose their pensions or will not be able to find work somewhere else feel trapped. Toxic environments can take a severe emotional toll on an employee. Leaving an unsatisfying job early may make retirement a relief.

- Retire “on time” — Retiring too early or too late can cause people to feel “out of sync” or to feel they have not achieved their goals.

Whereas these seven tips are helpful for a smooth transition to retirement, Wang also notes that people tend to be adaptable, and no matter how they do it, retirees will eventually adjust to their new lifestyles.

Successful aging and longevity

Increases in average life expectancy in the 20th century and evidence from twin studies, suggesting that genes account for only 25% of the variance in human life spans, have opened new questions about implications for individuals and society (Christensen, Doblhammer, Rau, & Vaupel, 2009). What environmental and behavioural factors contribute to a long and healthy life? Is it possible to intervene and slow processes of aging or to minimize cognitive decline, prevent dementia, and ensure life quality at the end of life (Fratiglioni, Paillard-Borg, & Winblad, 2004; Hertzog, Kramer, Wilson, & Lindenberger, 2009; Lang, Baltes, & Wagner, 2007)? Should interventions focus on late life, midlife, or indeed begin in early life? Suggestions that pathological change (e.g., dementia) is not an inevitable component of aging and that pathology could at least be delayed until the very end of life led to theories about successful aging and proposals about targets for intervention. John Rowe and Robert Kahn (1997) defined three criteria of successful aging: (1) the relative avoidance of disease, disability, and risk factors like high blood pressure, smoking, or obesity; (2) the maintenance of high physical and cognitive functioning; and (3) active engagement in social and productive activities. Although such definitions of successful aging are value-laden, research and behavioural interventions have subsequently been guided by this model. For example, research has suggested that age-related declines in cognitive functioning across the adult life span may be slowed through physical exercise and lifestyle interventions (Kramer & Erickson, 2007). It is recognized, however, that societal and environmental factors also play a role and that there is much room for social change and technical innovation to accommodate the needs of the Baby Boomers and later generations as they age in the decades to come.

We have seen that, over the course of their lives, most individuals are able to develop secure attachments; reason cognitively, socially, and morally; and create families and find appropriate careers. Eventually, however, as people enter into their 60s and beyond, the aging process leads to faster changes in our physical, cognitive, and social capabilities and needs. Life begins to come to its natural conclusion, resulting in the final life stage, beginning in the 60s, known as late adulthood.

Despite the fact that the body and mind are slowing, most older adults nevertheless maintain an active lifestyle, remain as happy as they were when younger — or are happier — and increasingly value their social connections with family and friends (Angner, Ray, Saag, & Allison, 2009). Quinn Kennedy, Mara Mather, and Laura Carstensen (2004) found that people’s memories of their lives became more positive with age, and David Myers and Ed Diener (1996) found that older adults tended to speak more positively about events in their lives, particularly their relationships with friends and family, than did younger adults.

The changes associated with aging do not affect everyone in the same way, and they do not necessarily interfere with a healthy life. Former Beatles drummer Ringo Starr celebrated his 80 birthday in 2020 with a livestreamed concert, and Rolling Stones singer Mick Jagger — who once supposedly said, “I’d rather be dead than singing ‘Satisfaction’ at 45” — continues to perform in his late 70s. The golfer Tom Watson nearly won the 2010 British Open golf tournament at the age of 59, playing against competitors in their 20s and 30s. People well into their 80s and 90s, such as the financier Warren Buffett, Jim Pattison, a prominent Vancouver philanthropist, Hazel McCallion, mayor of Mississauga in Ontario until she was 93, and actress Betty White, all enjoy highly productive and energetic lives.

Researchers are beginning to better understand the factors that allow some people to age better than others. For one, research has found that the people who are best able to adjust well to changing situations early in life are also able to better adjust later in life (Rubin, 2007; Sroufe, Collins, Egeland, & Carlson, 2009). Perceptions also matter. People who believe that the elderly are sick, vulnerable, and grumpy often act according to such beliefs (Nemmers, 2005), and other research has found that the elderly who had more positive perceptions about aging also lived longer (Levy, Slade, Kunkel, & Kasl, 2002).

Research on the influence of cultural values and beliefs on aging attitudes has been dominated by comparisons between Eastern versus Western cultures. This belief is inspired by the idea that Asian societies are influenced by Confucian values of filial piety and the practice of ancestor worship, which are thought to promote positive views of aging and high esteem for older adults (Davis, 1983; Ho, 1994; Sher, 1984). Western societies, in contrast, were thought to be youth-oriented and to hold more negative views about the aging process and the elderly (Palmore, 1975). Empirical evidence for the proposed East-West differences is scarce. Although some studies have found support for the notion that aging attitudes are more positive in Asian as compared to Western cultures (Levy & Langer, 1994; Tan, Zhang, & Fan, 2004), others report effects in the opposite direction (Giles et al., 2000; Harwood et al., 2001; Sharps, Price-Sharps, & Hanson, 1998; Zhou, 2007), or fail to find any marked cultural differences (Boduroglu, Yoon, Luo, & Park, 2006; Ryan, Jin, Anas, & Luh, 2004).

Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease

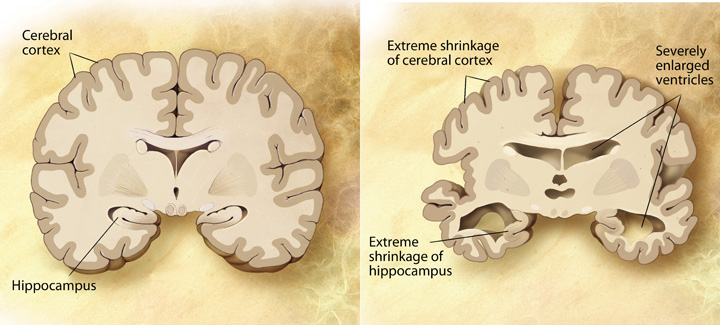

Some older adults suffer from biologically based cognitive impairments in which the brain is so adversely affected by aging that it becomes very difficult for the person to continue to function effectively. Dementia is defined as a progressive neurological disease that includes loss of cognitive abilities significant enough to interfere with everyday behaviours, and Alzheimer’s disease is a form of dementia that, over a period of years, leads to a loss of emotions, cognitions, and physical functioning, which is ultimately fatal. Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease are most likely to be observed in individuals who are 65 and older, and the likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease doubles about every five years after age 65. After age 85, the risk reaches nearly 8% per year (Hebert et al., 1995). Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease both produce a gradual decline in functioning of the brain cells that produce the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (see Figure 13.21). Without this neurotransmitter, the neurons are unable to communicate, leaving the brain less and less functional.

Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease are in part heritable, but there is increasing evidence that the environment also plays a role. Current research is helping us understand the things that older adults can do to help them slow down or prevent the negative cognitive outcomes of aging, including dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (Pushkar, Bukowski, Schwartzman, Stack, & White, 2007). Older adults who continue to keep their minds active by engaging in cognitive activities — such as reading, playing musical instruments, attending lectures, or doing crossword puzzles — who maintain social interactions with others, and who keep themselves physically fit have a greater chance of maintaining their mental acuity than those who do not (Cherkas et al., 2008; Verghese et al., 2003). In short, although physical illnesses may occur to anyone, the more people keep their brains active and the more they maintain a healthy and active lifestyle, the more likely their brains will remain healthy (Ertel, Glymour, & Berkman, 2008).

Death, dying, and bereavement

Living includes dealing with our own and our loved ones’ mortality. In her book On Death and Dying (1997), Elisabeth Kübler-Ross describes five phases of grief through which people pass in grappling with the knowledge that they or someone close to them is dying:

- Denial: “I feel fine.” “This can’t be happening. Not to me.”

- Anger: “Why me? It’s not fair!” “How can this happen to me?” “Who is to blame?”

- Bargaining: “Just let me live to see my children graduate.” “I’d do anything for a few more years.” “I’d give my life savings if . . .”

- Depression: “I’m so sad. Why bother with anything?” “I’m going to die. What’s the point?” “I miss my loved ones. Why go on?”

- Acceptance: “I know my time has come” “It’s almost my time.”

Despite Kübler-Ross’s popularity, there are a growing number of critics of her theory who argue that her five-stage sequence is too constraining because attitudes toward death and dying have been found to vary greatly across cultures and religions, and these variations make the process of dying different according to culture (Bonanno, 2009). As an example, Japanese-Americans restrain their grief (Corr, Nabe, & Corr, 2009) so as not to burden other people with their pain. By contrast, Jewish people observe a seven-day, publicly announced mourning period. In some cultures, the elderly are more likely to be living and coping alone, or perhaps only with their spouse, whereas in other cultures, such as the Hispanic culture, the elderly are more likely to be living with their children and other relatives, and this social support may create a better quality of life for them (Diaz-Cabello, 2004).

Margaret Stroebe, Robert Hansson, Henk Schut, and Wolfgang Stroebe (2008) found that although most people adjusted to the loss of a loved one without seeking professional treatment, many had an increased risk of mortality, particularly within the early weeks and months after the loss. These researchers also found that people going through the grieving process suffered more physical and psychological symptoms, were sick more often, and used more medical services.

The health of survivors during the end of life is influenced by factors such as circumstances surrounding the loved one’s death, individual personalities, and ways of coping. People serving as caretakers to partners or other family members who are ill frequently experience a great deal of stress themselves, making the dying process even more stressful. Despite the trauma of the loss of a loved one, people do recover and are able to continue with effective lives. Grief intervention programs can go a long way in helping people cope during the bereavement period (Neimeyer, Holland, Currier, & Mehta, 2008).

Source: Adapted from Queen and Smith (2020).

Key Takeaways

- Most older adults maintain an active lifestyle, remain as happy as they were when younger — or are happier — and increasingly value their social connections with family and friends.

- Although older adults have slower cognitive processing overall (i.e., fluid intelligence), their experience in the form of existing knowledge about the world and the ability to use it (i.e., crystallized intelligence) is maintained and even strengthened during old age.

- Expectancies about change in aging vary across cultures and may influence how people respond to getting older.

- A portion of the elderly suffer from age-related brain diseases, such as dementia, a progressive neurological disease that includes significant loss of cognitive abilities, and Alzheimer’s disease, a fatal form of dementia that is related to changes in the cerebral cortex.

- Two significant social stages in late adulthood are retirement and dealing with grief and bereavement. Studies show that a well-planned retirement can be a pleasant experience.

- A significant number of people going through the grieving process are at increased risk of mortality and physical and mental illness, but grief counselling can be effective in helping these people cope with their loss.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- How do the people in your culture view aging? What stereotypes are there about the elderly? Are there other ways that people in your society might learn to think about aging that would be more beneficial?

- Based on the information you have read in this section, what would you tell older adults that you know about how they can best maintain healthy physical and cognitive function into late adulthood?

Congratulations on completing Chapter 13! Remember to go back to the section on Approach and Pedagogy near the beginning of the book to learn more about how to get the most out of reading and learning the material in this textbook.

Image Attributions

Figure 13.17. Bucket List: Item 3 by Woody Hibbard is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 13.18. The Fountain of Youth by Alex Proimos is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 license.

Figure 13.19. Old Friends by Elliot Margolies is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 13.20. 2007 Dublin City Marathon (Ireland) by William Murphy is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

Figure 13.21. Alzheimer’s Disease Brain Comparison by Garrondo is in the public domain.

References

Angner, E., Ray, M. N., Saag, K. G., & Allison, J. J. (2009). Health and happiness among older adults: A community-based study. Journal of Health Psychology, 14, 503–512.

Antonucci, T. C. (2001). Social relations: An examination of social networks, social support and sense of control. In J. E. Birren & K. W. Schaie (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (5th ed., pp. 427–453). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Baltes, P. B. (1987). Theoretical propositions of lifespan developmental psychology: On the dynamics between growth and decline. Developmental Psychology, 23, 611–626.

Baltes, P. B., & Lindenberger, U. (1997). Emergence of powerful connection between sensory and cognitive functions across the adult life span: A new window to the study of cognitive aging? Psychology and Aging, 12, 12–21.

Baltes, P. B., Staudinger, U. M., & Lindenberger, U. (1999). Life-span psychology: Theory and application to intellectual functioning. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 471–506.

Birditt, K., & Antonucci, T. C. (2008). Life sustaining irritations? Relationship quality and mortality in the context of chronic illness. Social Science & Medicine, 67, 1291–1299.

Birren, J. E., & Schroots, J. J. F. (2006). Autobiographical memory and the narrative self over the life span. In J. E. Birren & K. Warner Schaie (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (6th ed. pp. 477–499). Burlingham, MA: Elsevier Academic Press.

Blanchard-Fields, F. (2007). Everyday problem solving and emotion: An adult development perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 26–31.

Blanchard-Fields, F., Mienaltowski, A., & Seay, R. B. (2007). Age differences in everyday problem-solving effectiveness: Older adults select more effective strategies for interpersonal problems. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62B(1), P61–P64.

Boduroglu, A., Yoon, C., Luo, T., & Park, C. D. (2006). Stereotypes about young and old adults: A comparison of Chinese and American Cultures. Gerontology, 52, 324–333.

Bonanno, G. (2009). The other side of sadness: What the new science of bereavement tells us about life after a loss. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Burke, D. M., Shafto, M. A., Craik, F. I. M., & Salthouse, T. A. (2008). Language and aging. In F. I. M. Craik & T. A. Salthouse (Eds.), The handbook of aging and cognition (3rd ed., pp. 373–443). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Carstensen, L. L. (1993). Motivation for social contact across the life span: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. In J. E. Jacobs (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1992: Developmental perspectives on motivation (pp. 209–254). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Carstensen, L. L., Gottman, J. M., & Levensen, R. W. (1995). Emotional behavior in long-term marriage. Psychology and Aging, 10, 140–149.

Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. American Psychologist, 54, 165–181.

Charles, S. T., & Carstensen, L. L. (2010). Social and emotional aging. Annual review of psychology, 61, 383–409.

Charness, N. (1981). Search in chess: Age and skill differences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 7, 467–476.

Cherkas, L. F., Hunkin, J. L., Kato, B. S., Richards, J. B., Gardner, J. P., Surdulescu, G. L., . . . Aviv, A. (2008). The association between physical activity in leisure time and leukocyte telomere length. Archives of Internal Medicine, 168, 154–158.

Christensen, K., Doblhammer, G., Rau, R., Vaupel, J. W. (2009). Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet, 374, 1196–208.

Corr, C. A., Nabe, C. M., & Corr, D. M. (2009). Death and dying: Life and living (6th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Craik, F. I. M. (2000). Age-related changes in human memory. In D. C. Park & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Cognitive aging: A primer (pp. 75–92). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Craik, F. I. M., & Bialystok, E. (2006). Cognition through the lifespan: mechanisms of change. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10, 131–138.

Davis, D. (1983). Long lives: Chinese elderly and the Communist revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Diaz-Cabello, N. (2004). The Hispanic way of dying: Three families, three perspectives, three cultures. Illness, Crisis, & Loss, 12(3), 239–255.

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Scollon, C. N. (2006). Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. American Psychologist, 61, 305.

Elder, G. H., Johnson, M. K., & Crosnoe, R. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 3-19). New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

Ertel, K. A., Glymour, M. M., & Berkman, L. F. (2008). Effects of social integration on preserving memory function in a nationally representative U.S. elderly population. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 1215–1220.

Fingerman, K. L., Berg, C. A., Smith, J., & Antonucci, T. C. (Eds.). (2011). Handbook of life-span development. New York, NY: Springer.

Fingerman, K. L., Chen, P. C., Hay, E., Cichy, K. E., & Lefkowitz, E. S. (2006). Ambivalent reactions in the parent and offspring relationship. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61, 152–160.

Fratiglioni, L., Paillard-Borg, S., & Winblad, B. (2004). An active and socially integrated lifestyle in late life might protect against dementia. Lancet Neurology, 3, 343–353.

Friedman, H. S., Tucker, J. S., Tomlinson-Keasey, C., Schwartz, J. E., Wingard, D. L., & Criqui, M. H. (1993). Does childhood personality predict longevity? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 176–185.

George, L. K. (2010). Still happy after all these years: Research frontiers on subjective well-being in later life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65(3), 331–339.

Giles, H., Noels, K., Ota, H., Ng, S., Gallois, C., Ryan, E., . . . Sachdev, I. (2000). Age vitality across eleven nations. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 21, 308–323.

Harwood, J., Giles, H., McCann, R. M., Cai, D., Somera, L. P., Ng, S. H., . . . Noels, K. (2001). Older adults’ trait ratings of three age-groups around the Pacific rim. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 16(2), 157–171.

Hasher, L., & Zacks, R. T. (1988). Working memory, comprehension, and aging: A review and a new view. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 22, pp. 193–225). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Hebert, L. E., Scherr, P. A., Beckett, L. A., Albert, M. S., Pilgrim, D. M., Chown, M. J., . . . Evans, D. A. (1995). Age-specific incidence of Alzheimer’s disease in a community population. Journal of the American Medical Association, 273(17), 1354–1359.

Hertzog, C., Kramer, A. F., Wilson, R. S., & Lindenberger, U. (2009). Enrichment effects on adult cognitive development: Can the functional capacity of older adults be preserved and enhanced? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9, 1–65

Ho, D. Y. (1994). Filial piety, authoritarian moralism, and cognitive conservatism in Chinese societies. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 120, 347–365.

Kahn, R. L., & Antonucci, T. C. (1980). Convoys over the life course: Attachment, roles, and social support. In P. B. Baltes & O. G. Brim (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (pp. 253–286). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Kennedy, Q., Mather, M., & Carstensen, L. L. (2004). The role of motivation in the age-related positivity effect in autobiographical memory. Psychological Science, 15, 208–214.

Kramer, A. F., & Erickson, K. I. (2007). Capitalizing on cortical plasticity: The influence of physical activity on cognition and brain function. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 342–348.

Kübler-Ross, E. (1997). On death and dying. New York, NY: Scribner.

Lang, F. R., Baltes, P. B., & Wagner, G. G. (2007). Desired lifetime and end-of-life desires across adulthood from 20 to 90: A dual-source information model. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 62B, 268–276.

Levy, B. (2009). Stereotype embodiment: A psychosocial approach to aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(6), 332–336

Levy, B., & Langer, E. (1994). Aging free from negative stereotypes: Successful memory in China among the American deaf. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(6), 989–997.

Levy, B. R., Slade, M. D., Kunkel, S. R., & Kasl, S. V. (2002). Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 261–270.

Lucas, R. E. (2007). Adaptation and the set-point model of subjective well-being: Does happiness change after major life events? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(2), 75–79.

Lucas, R. E., & Donnellan, A. B. (2011). Personality development across the life span: Longitudinal analyses with a national sample from Germany. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 847–861.

Magai, C. (2008). Long-lived emotions. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, & L. Feldman Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 376–392). New York, NY: Guilford.

Markus, H., & Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist, 41, 954–969.

McAdams, D. P. (2006). The redemptive self: Generativity and the stories Americans live by. Research in Human Development, 3(2-3), 81–100.

Mroczek, D. K. (2001). Age and emotion in adulthood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(3), 87–90.

Myers, D. G., & Diener, E. (1996). The pursuit of happiness. Scientific American, 274(5), 70–72.

Neimeyer, R. A., Holland, J. M., Currier, J. M., & Mehta, T. (2008). Meaning reconstruction in later life: Toward a cognitive-constructivist approach to grief therapy. In D. Gallagher-Thompson, A. Steffen, & L. Thompson (Eds.), Handbook of behavioral and cognitive therapies with older adults (pp. 264–277). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Nemmers, T. M. (2005). The influence of ageism and ageist stereotypes on the elderly. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 22(4), 11–20.

Palmore, E. (1975). What can the USA learn from Japan about aging? Gerontologist, 15, 64–67.

Park, D. C. (2000). The basic mechanisms accounting for age-related decline in cognitive function. In D. C. Park & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Cognitive aging: A primer (pp. 3–21). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Park, D. C., & Gutchess, A. H. (2000). Cognitive aging and everyday life. In D. C. Park & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Cognitive aging: A primer (pp. 217–232). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Persad, C. C., Abeles, N., Zacks, R. T., & Denburg, N. L. (2002). Inhibitory changes after age 60 and the relationship to measures of attention and memory. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57B(3), P223–P232.

Pushkar, D., Basevitz, P., Arbuckle, T., Nohara-LeClair, M., Lapidus, S., & Peled, M. (2000). Social behavior and off-target verbosity in elderly people. Psychology and Aging, 15(2), 361–374.

Pushkar, D., Bukowski, W. M., Schwartzman, A. E., Stack, D. M., & White, D. R. (2007). Responding to the challenges of late life: Strategies for maintaining and enhancing competence. New York, NY: Springer Publishing.

Queen, T., & Smith, J. (2020). Aging. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds.), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF. Retreived from http://noba.to/gtp7r548

Roberts, B. W., & Mroczek, D. K. (2008). Personality trait change in adulthood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17, 31–35.

Roberts, B. W., Kuncel, N., Shiner, R. N., Caspi, A., & Goldberg, L. R. (2007). The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2(4), 313–345.

Rook, K. S. (1998). Investigating the positive and negative sides of personal relationships: Through a lens darkly? In W. R. Cupach & B. H. Spitzberg (Eds.), The dark side of close relationships (pp. 369–393). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ross, M., & Wilson, A. E. (2003). Autobiographical memory and conceptions of self: Getting better all the time. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 66–69.

Rowe, J. W. (2009). Facts and fictions about an aging America. Contexts, 8, 16–21.

Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (1997). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 37(4), 433–440.

Rubin, D., & Berntsen, D. (2006). People over 40 feel 20% younger than their age: Subjective age across the lifespan. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 13, 776–780

Rubin, L. (2007). 60 on up: The truth about aging in America. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Ryan, E. B., Jin, Y. S., Anas, A. P., & Luh, J. (2004). Communication beliefs about youth and old age in Asia and Canada. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 19, 343–360.

Ryff, C. D. (1995). Psychological well-being in adult life. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4(4), 99–104

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. (2000). Interpersonal flourishing: A positive health agenda for the new millennium. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4, 30–44.

Salthouse, T. A. (1984). Effects of age and skill in typing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113(3), 345–371.

Salthouse, T. A. (2004). What and when of cognitive aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 140–144.

Schaie, K. W., & Willis, S. L. (1996). Psychometric intelligence and aging. In F. Blanchard-Fields & T. M. Hess (Eds.), Perspectives on cognitive change in adulthood and aging (pp. 293–322). New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Scheibe, S., Kunzmann, U., & Baltes, P. B. (2009). New territories of positive life-span development: Wisdom and life longings. In S. J. E. Lopez & C. R. E. Snyder (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology (2nd ed., pp. 171–183). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Settersten, R. A., Jr. (2005). Toward a stronger partnership between lifecourse sociology and life-span psychology. Research in Human Development, 2(1–2), 25–41.

Sharps, M. J., Price-Sharps, J. L., & Hanson, J. (1998). Attitudes of young adults toward older adults: Evidence from the United States and Thailand. Educational Gerontology, 24, 655–660.

Sher, A. (1984). Aging in post-Mao China: The politics of veneration. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Sroufe, L. A., Collins, W. A., Egeland, B., & Carlson, E. A. (2009). The development of the person: The Minnesota study of risk and adaptation from birth to adulthood. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Stone, A. A., Schwartz, J. E., Broderick, J. E., & Deaton, A. (2010). A snapshot of the age distribution of psychological well-being in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107, 9985–9990.

Stroebe, M. S., Hansson, R. O., Schut, H., & Stroebe, W. (2008). Bereavement research: Contemporary perspectives. In M. S. Stroebe, R. O. Hansson, H. Schut, & W. Stroebe (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement research and practice: Advances in theory and intervention (pp. 3–25). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Tan, P. P., Zhang, N., & Fan, L. (2004). Students’ attitude toward the elderly in the people’s Republic of China. Educational Gerontology, 30, 305–314.

Tentori, K., Osherson, D., Hasher, L., & May, C. (2001). Wisdom and aging: Irrational preferences in college students but not older adults. Cognition, 81, B87–B96.

Uchino, B. N. (2009). What a lifespan approach might tell us about why distinct measures of social support have differential links to physical health. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26(1), 53–62.

Umberson, D., Williams, K., Powers, D. A., Liu, H., & Needham, B. (2006). You make me sick: Marital quality and health over the life course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47, 1–16.

Verghese, J., Lipton, R., Katz, M. J., Hall, C. B., Derby, C. A., Kuslansky, G., . . . Buschke, M. D. (2003). Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. New England Journal of Medicine, 348, 2508–2516.

Waite, L. J. & Gallagher, M. (2000). The case for marriage: Why married people are happier, healthier, and better off financially. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Wang, M. (2007). Profiling retirees in the retirement transition and adjustment process: Examining the longitudinal change patterns of retirees’ psychological well-being. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 455–474.

Zhou, L. (2007). What college students know about older adults: A cross-cultural qualitative study. Educational Gerontology, 33, 811–831.