13.4 Adolescence: Developing Independence and Identity

Learning Objectives

- Summarize the physical and cognitive changes that occur for boys and girls during adolescence.

- Explain how adolescents develop a sense of morality and of self-identity.

- Describe major features of social development during adolescence.

- Be able to explain sources of diversity in adolescent development.

- Explain moral development in adolescence.

Adolescence is defined as the years between the onset of puberty and the beginning of adulthood. In the past, when people were likely to marry in their early 20s or younger, this period might have lasted only 10 years or less — starting roughly between ages 12 and 13 and ending by age 20, at which time the child got a job or went to work on the family farm, married, and started their own family. Today, children mature more slowly, move away from home at later ages, and maintain ties with their parents longer. For instance, children may go away to university but still receive financial support from parents, and they may come home on weekends or even to live for extended time periods. Thus, the period between puberty and adulthood may well last into the late 20s, merging into adulthood itself. In fact, it is appropriate now to consider the period of adolescence and that of emerging adulthood (i.e., the ages between 18 and the middle or late 20s) together.

During adolescence, the child continues to grow physically, cognitively, and emotionally, changing from a child into an adult. The body grows rapidly in size, and the sexual and reproductive organs become fully functional. At the same time, as adolescents develop more advanced patterns of reasoning and a stronger sense of self; they seek to forge their own identities, developing important attachments with people other than their parents. Particularly in Western societies, where the need to forge a new independence is critical (Baumeister & Tice, 1986; Twenge, 2006), this period can be stressful for many children, as it involves new emotions, the need to develop new social relationships, and an increasing sense of responsibility and independence.

Although adolescence can be a time of stress for many teenagers, most of them weather the trials and tribulations successfully. For example, the majority of adolescents experiment with alcohol sometime before high school graduation. Although many will have been drunk at least once, relatively few teenagers will develop long-lasting drinking problems or permit alcohol to adversely affect their school or personal relationships. Similarly, a great many teenagers break the law during adolescence, but very few young people develop criminal careers (Farrington, 1995). These facts do not, however, mean that using drugs or alcohol is a good idea. The use of recreational drugs can have substantial negative consequences, and the likelihood of these problems — including dependence, addiction, and even brain damage — is significantly greater for young adults who begin using drugs at an early age.

Physical changes in adolescence

Adolescence begins with the onset of puberty, a developmental period in which hormonal changes cause rapid physical alterations in the body, culminating in sexual maturity. Although the timing varies to some degree across cultures, the average age range for reaching puberty is between nine and 14 years for girls and between 10 and 17 years for boys (Marshall & Tanner, 1986).

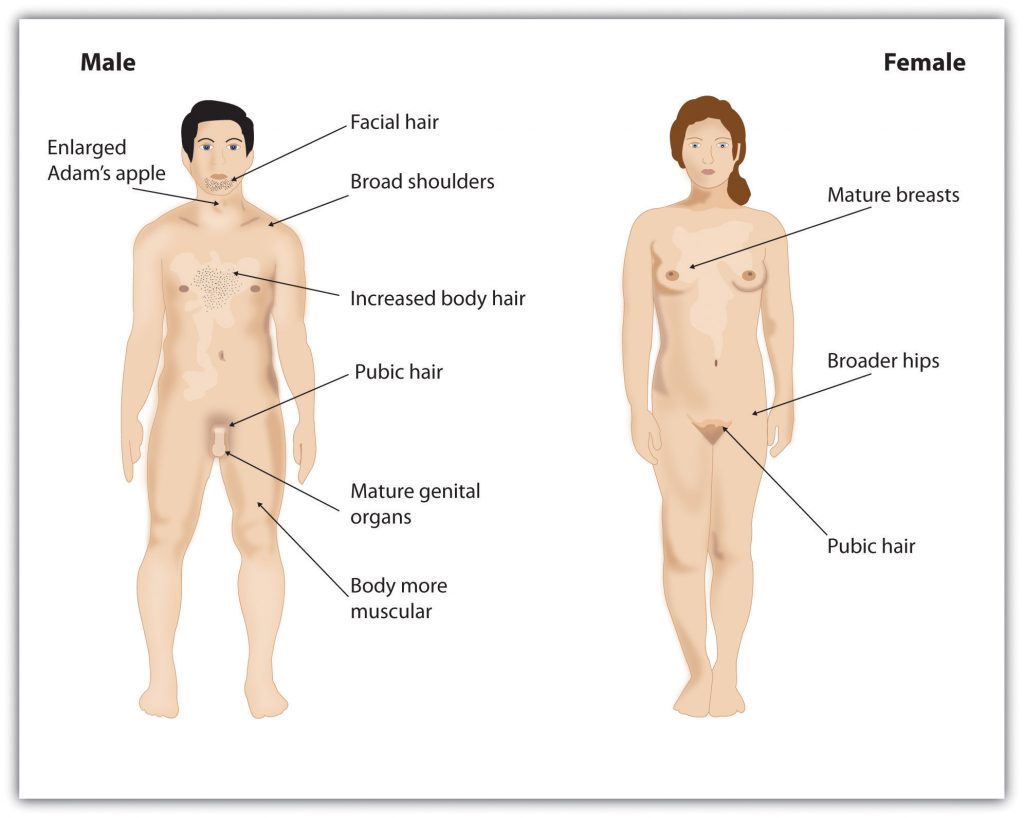

Puberty begins when the pituitary gland begins to stimulate the production of the male sex hormone testosterone in boys and the female sex hormones estrogen and progesterone in girls. The release of these sex hormones triggers the development of the primary sex characteristics, that is, the sex organs concerned with reproduction (see Figure 13.13). These changes include the enlargement of the testicles and the penis in boys and the development of the ovaries, uterus, and vagina in girls. In addition, secondary sex characteristics, which are features that distinguish the two sexes from each other but are not involved in reproduction, are also developing, such as an enlarged Adam’s apple, a deeper voice, pubic hair, and underarm hair in boys and enlargement of the breasts and hips as well as the appearance of pubic and underarm hair in girls (see Figure 13.13). The enlargement of breasts is usually the first sign of puberty in girls and, on average, occurs between ages 10 and 12 (Marshall & Tanner, 1986). Boys typically begin to grow facial hair between ages 14 and 16, and both boys and girls experience a rapid growth spurt during this stage. The growth spurt for girls usually occurs earlier than that for boys, with some boys continuing to grow into their 20s.

A major milestone in puberty for girls is menarche, the first menstrual period, typically experienced at around 12 or 13 years of age (Anderson, Dannal, & Must, 2003). The age of menarche varies substantially and is determined by genetics, as well as by diet and lifestyle, since a certain amount of body fat is needed to attain menarche. Girls who are very slim, who engage in strenuous athletic activities, or who are malnourished may begin to menstruate later. Even after menstruation begins, girls whose level of body fat drops below the critical level may stop having their periods. The sequence of events for puberty is more predictable than the age at which they occur. Some girls may begin to grow pubic hair at age 10 but not attain menarche until age 15. In boys, facial hair may not appear until 10 years after the initial onset of puberty.

The timing of puberty in both boys and girls can have significant psychological consequences. Boys who mature earlier attain some social advantages because they are taller and stronger and, therefore, often more popular (Lynne, Graber, Nichols, Brooks-Gunn, & Botvin, 2007). At the same time, however, early-maturing boys are at greater risk for delinquency and are more likely than their peers to engage in antisocial behaviours, including drug and alcohol use, truancy (i.e., skipping class), and precocious sexual activity. Girls who mature early may find their maturity stressful, particularly if they experience teasing or sexual harassment (Mendle, Turkheimer, & Emery, 2007; Pescovitz & Walvoord, 2007). Early-maturing girls are also more likely to have emotional problems, a lower self-image, and higher rates of depression, anxiety, and disordered eating than their peers (Ge, Conger, & Elder, 1996).

Cognitive development in adolescence

Although the most rapid cognitive changes occur during childhood, the brain continues to develop throughout adolescence and even into the 20s (Weinberger, Elvevåg, & Giedd, 2005). During adolescence, the brain continues to form new neural connections, but it also casts off unused neurons and connections (Blakemore, 2008). As teenagers mature, the prefrontal cortex — the area of the brain responsible for reasoning, planning, and problem solving — also continues to develop (Goldberg, 2001). Additionally, myelin, the fatty tissue that forms around axons and neurons and helps speed transmissions between different regions of the brain, also continues to grow (Rapoport et al., 1999).

Adolescents often seem to act impulsively, rather than thoughtfully, and this may be in part because the development of the prefrontal cortex is, in general, slower than the development of the emotional parts of the brain, including the limbic system (Blakemore, 2008). Furthermore, the hormonal surge that is associated with puberty, which primarily influences emotional responses, may create strong emotions and lead to impulsive behaviour. It has been hypothesized that adolescents may engage in risky behaviour — such as smoking, drug use, dangerous driving, and unprotected sex — in part because they have not yet fully acquired the mental ability to curb impulsive behaviour or to make entirely rational judgments (Steinberg, 2007).

The new cognitive abilities that are attained during adolescence may also give rise to new feelings of egocentrism, in which adolescents believe that they can do anything and that they know better than anyone else, including their parents (Elkind, 1978). Teenagers are likely to be highly self-conscious, often creating an imaginary audience in which they feel that everyone is constantly watching them (Goossens, Beyers, Emmen, & van Aken, 2002). Because teens think so much about themselves, they mistakenly believe that others must be thinking about them, too (Rycek, Stuhr, McDermott, Benker, & Swartz, 1998). It is no wonder that everything a teen’s parents do suddenly feels embarrassing to them when they are in public.

Social development in adolescence

Some of the most important changes that occur during adolescence involve the further development of the self-concept and the development of new attachments. Whereas young children are most strongly attached to their parents, the important attachments of adolescents move increasingly away from parents and increasingly toward peers (Harris, 1998). As a result, parents’ influence diminishes at this stage.

According to Erik Erikson (1950), the main social task of the adolescent is the search for a unique identity — the ability to answer the question “Who am I?” In the search for identity, the adolescent may experience role confusion in which they are balancing or choosing among identities, taking on negative or undesirable identities, or temporarily giving up looking for an identity altogether if things are not going well.

One approach to assessing identity development was proposed by James Marcia (1980). In this approach, adolescents are asked questions regarding their exploration of and commitment to issues related to occupation, politics, religion, and sexual behaviour. The responses to the questions allow the researchers to classify the adolescent into one of four identity categories, as shown in the table below.

| Stage | Identity Development |

| Identity-diffusion status | The individual does not have firm commitments regarding the issues in question and is not making progress toward them. |

| Foreclosure status | The individual has not engaged in any identity experimentation and has established an identity based on the choices or values of others. |

| Moratorium status | The individual is exploring various choices but has not yet made a clear commitment to any of them. |

| Identity-achievement status | The individual has attained a coherent and committed identity based on personal decisions. |

| Data source: Marcia, 1980. |

Studies assessing how teens pass through Marcia’s stages show that, although most teens eventually succeed in developing a stable identity, the path to it is not always easy and many routes can be taken. Some teens may simply adopt the beliefs of their parents or the first role that is offered to them, perhaps at the expense of searching for other, more promising possibilities, which is an example of foreclosure status. Other teens may spend years trying on different possible identities before finally choosing one, which is an example of moratorium status.

To help them work through the process of developing an identity, teenagers may well try out different identities in different social situations. They may maintain one identity at home and a different type of persona when they are with their peers. Eventually, most teenagers do integrate the different possibilities into a single self-concept and a comfortable sense of identity, which is an example of identity-achievement status.

For teenagers, the peer group provides valuable information about the self-concept. For instance, in response to the question “What were you like as a teenager? (e.g., cool, nerdy, awkward),” posed on the website Answerbag, one teenager replied in this way:

I’m still a teenager now, but from 8th–9th grade I didn’t really know what I wanted at all. I was smart, so I hung out with the nerdy kids. I still do; my friends mean the world to me. But in the middle of 8th I started hanging out with whom you may call the “cool” kids . . . and I also hung out with some stoners, just for variety. I pierced various parts of my body and kept my grades up. Now, I’m just trying to find who I am. I’m even doing my sophomore year in China so I can get a better view of what I want. (dojokills, 2007, answer 47)

Responses like this one demonstrate the extent to which adolescents are developing their self-concepts and self-identities and how they rely on peers to help them do that. The writer here is trying out several, perhaps conflicting, identities, and the identities any teen experiments with are defined by the group the person chooses to be a part of. The friendship groups (e.g., cliques, crowds, or gangs) that are such an important part of the adolescent experience allow the young adult to try out different identities, and these groups provide a sense of belonging and acceptance (Rubin, Bukowski, & Parker, 2006). A big part of what the adolescent is learning is social identity, which is the part of the self-concept that is derived from one’s group memberships. Adolescents define their social identities according to how they are similar to and differ from others, finding meaning in the sports, religious, school, gender, and ethnic categories they belong to.

Aggression and antisocial behaviour

Several major theories of the development of antisocial behaviour treat adolescence as an important period. Gerald Patterson’s (1982) early versus late starter model of the development of aggressive and antisocial behaviour distinguishes youths whose antisocial behaviour begins during childhood (i.e., early starters) versus adolescence (i.e., late starters). According to the theory, early starters are at greater risk for long-term antisocial behaviour that extends into adulthood than are late starters. Late starters who become antisocial during adolescence are theorized to experience poor parental monitoring and supervision, aspects of parenting that become more salient during adolescence. Poor monitoring and lack of supervision contribute to increasing involvement with deviant peers, which in turn promotes adolescents’ own antisocial behaviour. Late starters desist from antisocial behaviour when changes in the environment make other options more appealing. Similarly, Terrie Moffitt’s (1993) life-course-persistent versus adolescence-limited model distinguishes between antisocial behaviour that begins in childhood versus adolescence. Moffitt regards adolescence-limited antisocial behaviour as resulting from a “maturity gap” between adolescents’ dependence on and control by adults and their desire to demonstrate their freedom from adult constraint. However, as they continue to develop, and legitimate adult roles and privileges become available to them, there are fewer incentives to engage in antisocial behaviour, leading to desistance in these antisocial behaviours.

Anxiety and depression

Developmental models of anxiety and depression also treat adolescence as an important period, especially in terms of the emergence of gender differences in prevalence rates that persist through adulthood (Rudolph, 2009). Starting in early adolescence, compared with males, females have rates of anxiety that are about twice as high and rates of depression that are one and a half to three times as high (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Although the rates vary across specific anxiety and depression diagnoses, rates for some disorders are markedly higher in adolescence than in childhood or adulthood. For example, prevalence rates for specific phobias are about 5% in children, 3–5% in adults, but 16% in adolescents. Anxiety and depression are particularly concerning because suicide is one of the leading causes of death during adolescence. Developmental models focus on interpersonal contexts in both childhood and adolescence that foster depression and anxiety (e.g., Rudolph, 2009). Family adversity, such as abuse and parental psychopathology, during childhood sets the stage for social and behavioural problems during adolescence. Adolescents with such problems generate stress in their relationships (e.g., by resolving conflict poorly and excessively seeking reassurance) and select into more maladaptive social contexts (e.g., “misery loves company” scenarios in which depressed youths select other depressed youths as friends and then frequently co-ruminate as they discuss their problems, exacerbating negative affect and stress). These processes are intensified for girls compared with boys because girls have more relationship-oriented goals related to intimacy and social approval, leaving them more vulnerable to disruption in these relationships. Anxiety and depression then exacerbate problems in social relationships, which in turn contribute to the stability of anxiety and depression over time.

Academic achievement

Adolescents spend more waking time in school than in any other context (Eccles & Roeser, 2011). Academic achievement during adolescence is predicted by interpersonal (e.g., parental engagement in adolescents’ education), intrapersonal (e.g., intrinsic motivation), and institutional (e.g., school quality) factors. Academic achievement is important in its own right as a marker of positive adjustment during adolescence but also because academic achievement sets the stage for future educational and occupational opportunities. The most serious consequence of school failure, particularly dropping out of school, is the high risk of unemployment or underemployment in adulthood that follows. High achievement can set the stage for college or future vocational training and opportunities.

Diversity

Adolescent development does not necessarily follow the same pathway for all individuals. Certain features of adolescence, particularly with respect to biological changes associated with puberty and cognitive changes associated with brain development, are relatively universal. However, other features of adolescence depend largely on circumstances that are more environmentally variable. For example, adolescents growing up in one country might have different opportunities for risk taking than adolescents in a different country, and supports and sanctions for different behaviours in adolescence depend on laws and values that might be specific to where adolescents live. Likewise, different cultural norms regarding family and peer relationships shape adolescents’ experiences in these domains. For example, in some countries, adolescents’ parents are expected to retain control over major decisions, whereas in other countries, adolescents are expected to begin sharing in or taking control of decision making.

Even within the same country, adolescents’ gender, ethnicity, immigrant status, religion, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and personality can shape both how adolescents behave and how others respond to them, creating diverse developmental contexts for different adolescents. For example, early puberty, which occurs before most other peers have experienced puberty, appears to be associated with worse outcomes for girls than boys, likely because girls who enter puberty early tend to associate with older boys, which in turn is associated with early sexual behaviour and substance use. For adolescents who are ethnic or sexual minorities, discrimination sometimes presents a set of challenges that non-minorities do not face.

Finally, genetic variations contribute an additional source of diversity in adolescence. Current approaches emphasize gene X environment interactions, which often follow a differential susceptibility model (Belsky & Pluess, 2009). That is, particular genetic variations are considered riskier than others, but genetic variations also can make adolescents more or less susceptible to environmental factors. For example, the association between the CHRM2 genotype and adolescent externalizing behaviour (e.g., aggression and delinquency) has been found in adolescents whose parents are low in monitoring behaviours (Dick et al., 2011). Thus, it is important to bear in mind that individual differences play an important role in adolescent development.

Peers

As children become adolescents, they usually begin spending more time with their peers and less time with their families, and these peer interactions are increasingly unsupervised by adults. Children’s notions of friendship often focus on shared activities, whereas adolescents’ notions of friendship increasingly focus on intimate exchanges of thoughts and feelings. During adolescence, peer groups evolve from primarily single-sex to mixed-sex. Adolescents within a peer group tend to be similar to one another in behaviour and attitudes, which has been explained as being a function of homophily (i.e., adolescents who are similar to one another choose to spend time together in a “birds of a feather flock together” way) and influence (i.e., adolescents who spend time together shape each other’s behaviour and attitudes). One of the most widely studied aspects of adolescent peer influence is known as deviant peer contagion (Dishion & Tipsord, 2011), which is the process by which peers reinforce problem behaviour by laughing or showing other signs of approval that then increase the likelihood of future problem behaviour.

Peers can serve both positive and negative functions during adolescence. Negative peer pressure can lead adolescents to make riskier decisions or engage in more problematic behaviour than they would alone or in the presence of their family. For example, adolescents are much more likely to drink alcohol, use drugs, and commit crimes when they are with their friends than when they are alone or with their family. However, peers also serve as an important source of social support and companionship during adolescence, and adolescents with positive peer relationships are happier and better adjusted than those who are socially isolated or have conflictual peer relationships.

Crowds are an emerging level of peer relationships in adolescence. In contrast to friendships, which are reciprocal dyadic relationships, and cliques, which refer to groups of individuals who interact frequently, crowds are characterized more by shared reputations or images than actual interactions (Brown & Larson, 2009). These crowds reflect different prototypic identities, such as jocks or brains, and are often linked with adolescents’ social status and peers’ perceptions of their values or behaviours.

Romantic relationships

Adolescence is the developmental period during which romantic relationships typically first emerge. Initially, same-sex peer groups that were common during childhood expand into mixed-sex peer groups that are more characteristic of adolescence. Romantic relationships often form in the context of these mixed-sex peer groups (Connolly, Furman, & Konarski, 2000). Although romantic relationships during adolescence are often short-lived, rather than long-term committed partnerships, their importance should not be minimized. Adolescents spend a great deal of time focused on romantic relationships, and their positive and negative emotions are more tied to romantic relationships, or lack thereof, than to friendships, family relationships, or school (Furman & Shaffer, 2003). Romantic relationships contribute to adolescents’ identity formation, changes in family and peer relationships, and adolescents’ emotional and behavioural adjustment.

Furthermore, romantic relationships are centrally connected to adolescents’ emerging sexuality. Parents, policymakers, and researchers have devoted a great deal of attention to adolescents’ sexuality, in large part because of concerns related to sexual intercourse, contraception, and preventing teen pregnancies. However, sexuality involves more than this narrow focus. For example, adolescence is often when individuals who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender come to perceive themselves as such (Russell, Clarke, & Clary, 2009). Thus, romantic relationships are a domain in which adolescents experiment with new behaviours and identities.

Developing moral reasoning — Kohlberg’s theory

The independence that comes with adolescence requires independent thinking as well as the development of morality, which is the standards of behaviour that are generally agreed on within a culture to be right or proper. Just as Piaget believed that children’s cognitive development follows specific patterns, Lawrence Kohlberg (1984) argued that children learn their moral values through active thinking and reasoning, and their moral development follows a series of stages. To study moral development, Kohlberg posed moral dilemmas to children, teenagers, and adults, such as the following:

In Europe, a woman was near death from a special kind of cancer. There was one drug that the doctors thought might save her. It was a form of radium that a druggist in the same town had recently discovered. The drug was expensive to make, but the druggist was charging 10 times what the drug cost him to make. He paid $400 for the radium and charged $4,000 for a small dose of the drug. The sick woman’s husband, Heinz, went to everyone he knew to borrow the money and tried every legal means, but he could only get together about $2,000, which is half of what it cost. He told the druggist that his wife was dying and asked him to sell it cheaper or let him pay later, but the druggist said, “No, I discovered the drug and I’m going to make money from it.” So, having tried every legal means, Heinz gets desperate and considers breaking into the man’s store to steal the drug for his wife.

-

- Should Heinz steal the drug? Why or why not?

- Is it actually right or wrong for him to steal the drug? Why is it right or wrong?

- Does Heinz have a duty or obligation to steal the drug? Why or why not? (Kohlberg, 1984)

The following YouTube link provides a good example of the stages of Kohlberg’s theory:

- Video: Kohlberg’s Moral Development Theory (FloatOnOkay, 2007)

As you can see in the table below, Kohlberg concluded, on the basis of their responses to the moral questions, that, as children develop intellectually, they pass through three stages of moral thinking: the preconventional level, the conventional level, and the postconventional level.

| Age | Moral Stage | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Young children | Preconventional morality | Until about the age of nine, children focus on self-interest. At this stage, punishment is avoided and rewards are sought. A person at this level will argue, “The man shouldn’t steal the drug, as he may get caught and go to jail.” |

| Older children, adolescents, most adults | Conventional morality | By early adolescence, the child begins to care about how situational outcomes impact others and wants to please and be accepted. At this developmental phase, people are able to value the good that can be derived from holding to social norms in the form of laws or less formalized rules. For example, a person at this level may say, “He should not steal the drug, as everyone will see him as a thief, and his wife, who needs the drug, wouldn’t want to be cured because of thievery,” or, “No matter what, he should obey the law because stealing is a crime.” |

| Many adults | Postconventional morality | At this stage, individuals employ abstract reasoning to justify behaviours. Moral behaviour is based on self-chosen ethical principles that are generally comprehensive and universal, such as justice, dignity, and equality. Someone with self-chosen principles may say, “The man should steal the drug to cure his wife and then tell the authorities that he has done so. He may have to pay a penalty, but at least he has saved a human life.” |

| Data source: Kohlberg, 1984. | ||

Although research has supported Kohlberg’s idea that moral reasoning changes from an early emphasis on punishment, social rules, and regulations to an emphasis on more general ethical principles, as with Piaget’s approach, Kohlberg’s stage model is probably too simple. For one, children may use higher levels of reasoning for some types of problems but revert to lower levels in situations where doing so is more consistent with their goals or beliefs (Rest, 1979). Second, it has been argued that the stage model is particularly appropriate for Western, rather than non-Western, samples in which allegiance to social norms, such as respect for authority, may be particularly important (Haidt, 2001). As well, there is frequently little correlation between how children score on the moral stages and how they behave in real life.

Perhaps the most important critique of Kohlberg’s theory is that it may describe the moral development of boys better than it describes that of girls. Carol Gilligan (1982) has argued that, because of differences in their socialization, males tend to value principles of justice and rights, whereas females value caring for and helping others. Although there is little evidence that boys and girls score differently on Kohlberg’s stages of moral development (Turiel, 1998), it is true that girls and women tend to focus more on issues of caring, helping, and connecting with others than do boys and men (Jaffee & Hyde, 2000). If you don’t believe this, ask yourself when you last got a thank-you note from a man.

Source: Adapted from Lansford (2020).

Key Takeaways

- Adolescence is the period of time between the onset of puberty and emerging adulthood.

- Emerging adulthood is the period from age 18 years until the mid-20s in which young people begin to form bonds outside the family, attend university, and find work. Even so, they tend not to be fully independent and have not taken on all the responsibilities of adulthood. This stage is most prevalent in Western cultures.

- Puberty is a developmental period in which hormonal changes cause rapid physical alterations in the body.

- The cerebral cortex continues to develop during adolescence and early adulthood, enabling improved reasoning, judgment, impulse control, and long-term planning.

- Adolescent development is characterized by social change as adolescents become more independent, spend more time with peers, explore romantic relationships and sexuality, and engage in more risk-taking behaviour.

- The developmental context for adolescence has wide variability including country, culture, sexual orientation, and so on.

- A defining aspect of adolescence is the development of a consistent and committed self-identity. The process of developing an identity can take time, but most adolescents succeed in developing a stable identity.

- Kohlberg’s theory proposes that moral reasoning is divided into the following stages: preconventional morality, conventional morality, and postconventional morality.

- Kohlberg’s theory of morality has been expanded and challenged, particularly by Gilligan, who has focused on differences in morality between boys and girls.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Based on what you learned in this section, do you think that people should be allowed to drive at age 16? Why or why not? At what age do you think they should be allowed to vote and to drink alcohol?

- Think about your experiences in high school. What sort of cliques or crowds were there? How did people express their identities in these groups? How did you use your groups to define yourself and develop your own identity?

Image Attributions

Figure 13.13. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 13.14. Fight by Philippe Put is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 13.15. Friends are Happy Together is used under a CC0 1.0 license.

Figure 13.16. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Anderson, S. E., Dannal, G. E., & Must, A. (2003). Relative weight and race influence average age at menarche: Results from two nationally representative surveys of U.S. girls studied 25 years apart. Pediatrics, 111, 844–850.

Baumeister, R. F., & Tice, D. M. (1986). How adolescence became the struggle for self: A historical transformation of psychological development. In J. Suls & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on the self (Vol. 3, pp. 183–201). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Belsky, J., & Pluess, M. (2009). Beyond diathesis-stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 885–908.

Blakemore, S. J. (2008). Development of the social brain during adolescence. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61, 40–49.

Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 74–103). New York, NY: Wiley.

Connolly, J., Furman, W., & Konarski, R. (2000). The role of peers in the emergence of heterosexual romantic relationships in adolescence. Child Development, 71, 1395–1408.

Dick, D. M., Meyers, J. L., Latendresse, S. J., Creemers, H. E., Lansford, J. E., . . . Huizink, A. C. (2011). CHRM2, parental monitoring, and adolescent externalizing behavior: Evidence for gene-environment interaction. Psychological Science, 22, 481–489.

Dishion, T. J., & Tipsord, J. M. (2011). Peer contagion in child and adolescent social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 189–214.

Dojokills. (2007, March 20). What were you like as a teenager? (eg cool, nerdy, awkward?) [Online forum comment]. Answerbag. Retrieved from http://www.answerbag.com/q_view/171753

Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 225–241.

Elkind, D. (1978). The child’s reality: Three developmental themes. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York, NY: Norton.

Farrington, D. P. (1995). The challenge of teenage antisocial behavior. In M. Rutter & M. E. Rutter (Eds.), Psychosocial disturbances in young people: Challenges for prevention (pp. 83–130). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

FloatOnOkay. (2007, November 8). Kohlberg’s moral development theory [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=zY4etXWYS84&feature=emb_title

Furman, W., & Shaffer, L. (2003). The role of romantic relationships in adolescent development. In P. Florsheim (Ed.), Adolescent romantic relations and sexual behavior: Theory, research, and practical implications (pp. 3–22). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Ge, X., Conger, R. D., & Elder, G. H., Jr. (1996). Coming of age too early: Pubertal influences on girls’ vulnerability to psychological distress. Child Development, 67(6), 3386–3400.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Goldberg, E. (2001). The executive brain: Frontal lobes and the civilized mind. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Goossens, L., Beyers, W., Emmen, M., & van Aken, M. (2002). The imaginary audience and personal fable: Factor analyses and concurrent validity of the “new look” measures. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 12(2), 193–215.

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814–834.

Harris, J. (1998). The nurture assumption — Why children turn out the way they do. New York, NY: Free Press.

Jaffee, S., & Hyde, J. S. (2000). Gender differences in moral orientation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 126(5), 703–726.

Kohlberg, L. (1984). The psychology of moral development: Essays on moral development (Vol. 2, p. 200). San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row.

Lansford, J. (2020). Adolescent development. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds.), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF. Retrieved from http://noba.to/btay62sn

Lynne, S. D., Graber, J. A., Nichols, T. R., Brooks-Gunn, J., & Botvin, G. J. (2007). Links between pubertal timing, peer influences, and externalizing behaviors among urban students followed through middle school. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 181.e7–181.e13 (p. 198).

Marcia, J. (1980). Identity in adolescence. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, 5, 145–160.

Marshall, W. A., & Tanner, J. M. (1986). Puberty. In F. Falkner & J. M. Tanner (Eds.), Human growth: A comprehensive treatise (2nd ed., pp. 171–209). New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Mendle, J., Turkheimer, E., & Emery, R. E. (2007). Detrimental psychological outcomes associated with early pubertal timing in adolescent girls. Developmental Review, 27, 151–171.

Moffitt, T. E. (1993). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review, 100, 674–701.

Patterson, G. R. (1982). Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castalia Press.

Pescovitz, O. H., & Walvoord, E. C. (2007). When puberty is precocious: Scientific and clinical aspects. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press.

Rapoport, J. L., Giedd, J. N., Blumenthal, J., Hamburger, S., Jeffries, N., Fernandez, T.,…Evans, A. (1999). Progressive cortical change during adolescence in childhood-onset schizophrenia: A longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(7), 649–654.

Rest, J. (1979). Development in judging moral issues. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., & Parker, J. G. (2006). Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 571–645). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Rudolph, K. D. (2009). The interpersonal context of adolescent depression. In S. Nolen-Hoeksema & L. M. Hilt (Eds.), Handbook of depression in adolescents (pp. 377–418). New York, NY: Taylor and Francis.

Russell, S. T., Clarke, T. J., & Clary, J. (2009). Are teens “post-gay”? Contemporary adolescents’ sexual identity labels. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 884–890.

Rycek, R. F., Stuhr, S. L., McDermott, J., Benker, J., & Swartz, M. D. (1998). Adolescent egocentrism and cognitive functioning during late adolescence. Adolescence, 33, 746–750.

Steinberg, L. (2007). Risk taking in adolescence: New perspectives from brain and behavioral science. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16, 55–59.

Turiel, E. (1998). The development of morality. In W. Damon (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Socialization (5th ed., Vol. 3, pp. 863–932). New York, NY: Wiley.

Twenge, J. M. (2006). Generation me: Why today’s young Americans are more confident, assertive, entitled — and more miserable than ever before. New York, NY: Free Press.

Weinberger, D. R., Elvevåg, B., & Giedd, J. N. (2005). The adolescent brain: A work in progress. Retrieved from https://mdcune.psych.ucla.edu/ncamp/files-fmri/NCamp_fMRI_AdolescentBrain.pdf