11.3 Motivation: Food and Sex

Learning Objectives

- Identify the key properties of drive states.

- Describe biological goals accomplished by drive states.

- Give examples of drive states.

- Outline the neurobiological basis of drive states such as hunger and arousal.

- Discuss the main moderators and determinants of drive states such as hunger and arousal.

- Describe obesity and eating disorders.

- Explain the importance of Alfred Kinsey’s research on human sexuality.

- Explain the contributions that William Masters and Virginia Johnson’s research made to our understanding of the sexual response cycle.

Drive states

Our thoughts and behaviours are strongly influenced by affective experiences known as drive states. These drive states motivate us to fulfill goals that are beneficial to our survival and reproduction. This section provides an overview of key drive states, including information about their neurobiology and their psychological effects.

What is the longest you have ever gone without eating? A couple of hours? An entire day? How did it feel? Humans rely critically on food for nutrition and energy, and the absence of food can create drastic changes, not only in physical appearance, but in thoughts and behaviours as well. If you have ever fasted for a day, you probably noticed how hunger can take over your mind, directing your attention to foods you could be eating (e.g., a cheesy slice of pizza or perhaps some sweet, cold ice cream), and motivating you to obtain and consume these foods. Once you have eaten and your hunger has been satisfied, your thoughts and behaviours return to normal.

Hunger is a drive state, an affective experience — meaning that it is something you feel, like the sensation of being tired or hungry — that motivates organisms to fulfill goals that are generally beneficial to their survival and reproduction. Like other drive states, such as thirst or sexual arousal, hunger has a profound impact on the functioning of the mind. It affects psychological processes, such as perception, attention, emotion, and motivation, and it influences the behaviours that these processes generate.

Key properties of drive states

Drive states differ from other affective or emotional states in terms of the biological functions they accomplish. Whereas all affective states possess valence (i.e., they are positive or negative) and serve to motivate approach or avoidance behaviours (Zajonc, 1998), drive states are unique in that they generate behaviours that result in specific benefits for the body. For example, hunger directs individuals to eat foods that increase blood sugar levels in the body, while thirst causes individuals to drink fluids that increase water levels in the body.

Different drive states have different triggers. Most drive states respond to both internal and external cues, but the combinations of internal and external cues, and the specific types of cues, differ between drives. Hunger, for example, depends on internal, visceral signals as well as sensory signals, such as the sight or smell of tasty food. Different drive states also result in different cognitive and emotional states; hence, they may be associated with different behaviours. Yet, despite these differences, there are a number of properties common to all drive states.

Homeostasis

Humans, like all organisms, need to maintain a stable state in their various physiological systems. For example, the excessive loss of body water results in dehydration, a dangerous and potentially fatal state. However, too much water can be damaging as well. Thus, a moderate and stable level of body fluid is ideal. The tendency of an organism to maintain this stability across all the different physiological systems in the body is called homeostasis.

Homeostasis is maintained via two key factors. First, the state of the system being regulated must be monitored and compared to an ideal level, or a set point. Second, there needs to be mechanisms for moving the system back to this set point — that is, to restore homeostasis when deviations from it are detected. To better understand this, think of the thermostat in your own home. It detects when the current temperature in the house is different than the temperature you have it set at (i.e., the set point). Once the thermostat recognizes the difference, the heating or air conditioning turns on to bring the overall temperature back to the designated level.

Many homeostatic mechanisms, such as blood circulation and immune responses, are automatic and unconscious. Others, however, involve deliberate action. Most drive states motivate action to restore homeostasis using both “punishments” and “rewards.” Imagine that these homeostatic mechanisms are like protective parents. When you behave poorly by departing from the set point, such as not eating or being somewhere too cold, they raise their voice at you. You experience this as the bad feelings, or punishments, of hunger, thirst, or feeling too cold or too hot. However, when you behave well, such as eating nutritious foods when hungry, these homeostatic parents reward you with the pleasure that comes from any activity that moves the system back toward the set point. For example, when body temperature declines below the set point, any activity that helps to restore homeostasis, such as putting one’s hand in warm water, feels pleasurable. Likewise, when body temperature rises above the set point, anything that cools it feels pleasurable.

The narrowing of attention

As drive states intensify, they direct attention toward elements, activities, and forms of consumption that satisfy the biological needs associated with the drive. Hunger, for example, draws attention toward food. Outcomes and objects that are not related to satisfying hunger lose their value (Easterbrook, 1959). For instance, has anyone ever invited you to do a fun activity while you were hungry? Likely your response was something like: “I’m not doing anything until I eat first.” Indeed, at a sufficient level of intensity, individuals will sacrifice almost any quantity of goods that do not address the needs signaled by the drive state. For example, cocaine addicts, according to Frank Gawin (1991), “report that virtually all thoughts are focused on cocaine during binges; nourishment, sleep, money, loved ones, responsibility, and survival lose all significance” (p. 1581).

Drive states also produce a second form of attention-narrowing: a collapsing of time-perspective toward the present. That is, they make us impatient. While this form of attention-narrowing is particularly pronounced for the outcomes and behaviours directly related to the biological function being served by the drive state at issue (e.g., “I need food now”), it applies to general concerns for the future as well. Dan Ariely and George Loewenstein (2006), for example, investigated the impact of sexual arousal on the thoughts and behaviours of a sample of male undergraduates. These undergraduates were lent laptop computers that they took to their private residences, where they answered a series of questions, both in normal states and in states of high sexual arousal. Ariely and Loewenstein found that being sexually aroused made people extremely impatient for both sexual outcomes and for outcomes in other domains, such as those involving money. In another study, Louis Giordano and colleagues (Giordano et al., 2002) found that heroin addicts were more impatient with respect to heroin when they were craving it than when they were not. More surprisingly, they were also more impatient toward money (i.e., they valued delayed money less) when they were actively craving heroin.

Yet, a third form of attention-narrowing involves thoughts and outcomes related to the self versus others. Intense drive states tend to narrow one’s focus inwardly and to undermine altruism, which is the desire to do good for others. People who are hungry, in pain, or craving drugs tend to be selfish. Indeed, popular interrogation methods involve depriving individuals of sleep, food, or water, so as to trigger intense drive states leading the subject of the interrogation to divulge information that may betray comrades, friends, and family (Biderman, 1960).

Two illustrative drive states

Thus far, we have considered drive states abstractly. We have discussed the ways in which they relate to other affective and motivational mechanisms, as well as their main biological purpose and general effects on thought and behaviour. Yet, despite serving the same broader goals, different drive states are often remarkably different in terms of their specific properties. To understand some of these specific properties, we will explore two different drive states that play very important roles in determining behaviour and in ensuring human survival: hunger and sexual arousal.

Hunger

Hunger is a classic example of a drive state, one that results in thoughts and behaviours related to the consumption of food. Hunger is generally triggered by low glucose levels in the blood (Rolls, 2000), and behaviours resulting from hunger aim to restore homeostasis regarding those glucose levels. Various other internal and external cues can also cause hunger. For example, when fats are broken down in the body for energy, this initiates a chemical cue that the body should search for food (Greenberg, Smith, & Gibbs, 1990). External cues include the time of day, estimated time until the next feeding (e.g., hunger increases immediately prior to food consumption), and the sight, smell, taste, and even touch of food and food-related stimuli. Note that while hunger is a generic feeling, it has nuances that can provoke the eating of specific foods that correct for nutritional imbalances we may not even be conscious of. For example, a couple who was lost adrift at sea found they inexplicably began to crave the eyes of fish. Only later, after they had been rescued, did they learn that fish eyes are rich in vitamin C, a very important nutrient that they had been depleted of while lost in the ocean (Walker, 2014).

The hypothalamus, located in the lower central part of the brain, plays a very important role in eating behaviour. It is responsible for synthesizing and secreting various hormones. The lateral hypothalamus (LH) is concerned largely with hunger. In fact, lesions (i.e., damage) of the LH can eliminate the desire for eating entirely — to the point that animals starve themselves to death unless kept alive by force-feeding (Anand & Brobeck, 1951). Additionally, artificially stimulating the LH, using electrical currents, can generate eating behaviour if food is available (Andersson, 1951).

Activation of the LH can not only increase the desirability of food but can also reduce the desirability of nonfood-related items. For example, Miguel Brendl, Arthur Markman, and Claude Messner (2003) found that participants who were given a handful of popcorn to trigger hunger not only had higher ratings of food products, but also had lower ratings of nonfood products compared with participants whose appetites were not similarly primed. That is, because eating had become more important, other non-food products lost some of their value.

Hunger is only part of the story of when and why we eat. A related process, satiation, refers to the decline of hunger and the eventual termination of eating behaviour. Whereas the feeling of hunger gets you to start eating, the feeling of satiation gets you to stop. Perhaps surprisingly, hunger and satiation are two distinct processes, controlled by different circuits in the brain and triggered by different cues. Distinct from the LH, which plays an important role in hunger, the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) plays an important role in satiety. Though lesions of the VMH can cause an animal to overeat to the point of obesity, the relationship between the LH and the VMH is quite complicated. Rats with VMH lesions can also be quite finicky about their food (Teitelbaum, 1955).

Other brain areas, besides the LH and VMH, also play important roles in eating behaviour. For example, the sensory cortices — visual, olfactory, and taste — are important in identifying food items. These areas provide informational value, however, not hedonic evaluations. That is, these areas help tell a person what is good or safe to eat, but they do not provide the pleasure (i.e., hedonic) sensations that actually eating the food produces. While many sensory functions are roughly stable across different psychological states, other functions, such as the detection of food-related stimuli, are enhanced when the organism is in a hungry drive state.

After identifying a food item, the brain also needs to determine its reward value, which affects the organism’s motivation to consume the food. The reward value ascribed to a particular item is, not surprisingly, sensitive to the level of hunger experienced by the organism. The hungrier you are, the greater the reward value of the food. Neurons in the areas where reward values are processed, such as the orbitofrontal cortex, fire more rapidly at the sight or taste of food when the organism is hungry relative to if it is satiated.

How we eat is also influenced by our environment. When researchers rigged clocks to move faster, people got hungrier and ate more, as if they thought they must be hungry again because so much time had passed since they last ate (Schachter, 1968). Additionally, if we forget that we have already eaten, we are likely to eat again, even if we are not actually hungry (Rozin, Dow, Moscovitch, & Rajaram, 1998).

Cultural norms about appropriate weights also influence eating behaviours. Current norms for women in Western societies are based on a very thin body ideal, emphasized by television and movie actresses, models, and even children’s dolls, such as the ever-popular Barbie. These norms for excessive thinness are very difficult for most women to attain. For example, Barbie’s measurements, if translated to human proportions, would be about 91 cm bust/46 cm waist/84 cm hips, measurements that are attained by less than one in 100,000 women (Norton, Olds, Olive, & Dank, 1996). Many women idealize being thin, yet they are unable to reach the standard that they prefer.

Obesity

According to Statistics Canada (2019a), about 60% of Canadians over age 18 are overweight or obese as measured by body mass index (BMI), a measurement that compares one’s weight and height. If you know your height and weight, you can compute your BMI; refer to “Calculate Your Body Mass Index” (n.d.) by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. A BMI of 18.5 to 24.9 is considered healthy, while between 25 and 29.9 is overweight, and 30 or over is considered obese. Health risks rise with increased BMI. In addition to causing people to be stereotyped and treated less positively by others (Crandall, Merman, & Hebl, 2009), obesity leads to health problems including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, sleep apnea, arthritis, Alzheimer’s disease, and some types of cancer (Gustafson, Rothenberg, Blennow, Steen, & Skoog, 2003). Obesity also reduces life expectancy (Haslam & James, 2005). Obesity is a leading cause of death worldwide and is one of the most serious public health problems of the 21st century.

Although obesity is caused in part by genetics, it is increased by overeating and a lack of physical activity (James, 2008; Nestle & Jacobson, 2000). There are really only two approaches to controlling weight: eat less and exercise more. Dieting is difficult for anyone, but it is particularly difficult for people with slow basal metabolic rates who must cope with severe hunger to lose weight. Although most weight loss can be maintained for about a year, very few people are able to maintain substantial weight loss through dieting alone for more than three years (Miller, 1999). Substantial weight loss of more than 50 pounds is typically seen only when weight loss surgery has been performed (Douketis, Macie, Thabane, & Williamson, 2005). Weight loss surgery reduces stomach volume or bowel length, leading to earlier satiation and reduced ability to absorb nutrients from food.

Although dieting alone does not produce a great deal of weight loss over time, its effects are substantially improved when it is accompanied by more physical activity. People who exercise regularly, and particularly those who combine exercise with dieting, are less likely to be obese (Borer, 2008). Exercise not only improves our waistline but also makes us healthier overall. Exercise increases cardiovascular capacity, lowers blood pressure, and helps improve diabetes, joint flexibility, and muscle strength (American Heart Association, 1998). Exercise also slows the cognitive impairments that are associated with aging (Kramer, Erickson, & Colcombe, 2006).

Because the costs of exercise are immediate but the benefits are long-term, it may be difficult for people who do not exercise to get started. It is important to make a regular schedule, to work exercise into one’s daily activities, and to view exercise not as a cost but as an opportunity to improve oneself (Schomer & Drake, 2001). Exercising is more fun when it is done in groups, so team exercise is recommended (Kirchhoff, Elliott, Schlichting, & Chin, 2008). Exercise is important throughout life but may be easier to maintain if it is a habit acquired during childhood. Unfortunately, physical activity tends to decrease with age, especially for girls who already exercise less than boys, and only one-third of Canadian children meet the recommended one hour of physical activity per day. (Statistics Canada, 2017).

Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (2019) recommend that adults accumulate at least 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity a week to obtain substantial health benefits. The guidelines also suggest five- to 17-year-olds should accumulate at least 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity daily. Statistics Canada (2019b) reports that just over half of Canadians self-report that they meet this standard, although this is not the most reliable reporting method. Almost half of the people who start an exercise regimen give it up by the six-month mark (American Heart Association, 1998; Colley, Garriguet, Janssen, Craig, Clarke, & Tremblay, 2011).

It is clear that people eat more than is necessary, but there are complex reasons relating to age, activity level, food availability, culture and so on. The psychology of eating requires us to look beyond eating due to hunger and examine interactions with some of these other factors.

Eating disorders

While the majority of Canadian adults are overweight, a smaller, but significant, portion of the population has eating disorders associated with being normal weight or underweight. Often, these individuals are fearful of gaining weight. Individuals who suffer from bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa face many adverse health consequences (Mayo Clinic, 2012a, 2012b).

People suffering from bulimia nervosa engage in binge eating behaviour that is followed by purging. Purging the food involves inducing vomiting or the use of laxatives. Some affected individuals engage in excessive amounts of exercise to compensate for their binges. Bulimia is associated with many adverse health consequences that can include dehydration, kidney failure, heart failure, and tooth decay. In addition, these individuals often suffer from anxiety and depression, and they are at an increased risk for substance abuse (Mayo Clinic, 2012b). The lifetime prevalence rate for bulimia nervosa is estimated at around 1% for women and less than 0.5% for men (Smink, van Hoeken, & Hoek, 2012).

Binge eating disorder is a disorder recognized by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). Unlike with bulimia, as eating binges are not followed by inappropriate behaviour, such as purging, but they are followed by distress, including feelings of guilt, depression, and embarrassment. The resulting psychological distress distinguishes binge eating disorder from overeating (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Anorexia nervosa is an eating disorder characterized by the maintenance of a body weight well below average through starvation and possibly excessive exercise. Individuals suffering from anorexia nervosa often have a distorted body image, also known as body dysmorphia, meaning that they view themselves as overweight even though they are not. Like bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa is associated with a number of significant negative health outcomes: heart and kidney problems, low blood iron, bone loss, digestive problems, low heart rate, low blood pressure, fertility problems in women, and up to a 10% mortality rate (Canadian Mental Health Association, n.d.). Furthermore, there is an increased risk for a number of psychological problems, which include anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and substance abuse (Mayo Clinic, 2012a). Estimates of the prevalence of anorexia nervosa vary from study to study but generally range from just under 1% to just over 4% in women. Generally, prevalence rates are considerably lower for men (Smink et al., 2012).

While both anorexia and bulimia nervosa occur in men and women of many different cultures, Caucasian females from Western societies tend to be the most at-risk population. Recent research indicates that females between the ages of 15 and 19 are most at risk (see Figure 11.16), and it has long been suspected that these eating disorders are culturally-bound phenomena that are related to messages of a thin ideal often portrayed in popular media and the fashion world (Smink et al., 2012). While social factors play an important role in the development of eating disorders, there is also evidence that genetic factors may predispose people to these disorders (Collier & Treasure, 2004).

Sexual arousal

A second drive state, especially critical to reproduction, is sexual arousal. Sexual arousal results in thoughts and behaviours related to sexual activity. As with hunger, it is generated by a large range of internal and external mechanisms that are triggered either after the extended absence of sexual activity or by the immediate presence and possibility of sexual activity shown by cues commonly associated with such possibilities. Unlike hunger, however, these mechanisms can differ substantially between males and females, indicating important evolutionary differences in the biological functions that sexual arousal serves for different sexes.

Physiological mechanisms of sexual behaviour and motivation

Much of what we know about the physiological mechanisms that underlie sexual behaviour and motivation comes from animal research. As you have learned, the hypothalamus plays an important role in motivated behaviours, and sex is no exception. In fact, lesions to an area of the hypothalamus, called the medial preoptic area, completely disrupt a male rat’s ability to engage in sexual behaviour. Surprisingly, medial preoptic lesions do not change how hard a male rat is willing to work to gain access to a sexually receptive female (see Figure 11.18). This suggests that the ability to engage in sexual behaviour, and the motivation to do so, may be mediated by neural systems distinct from one another.

Animal research suggests that limbic system structures such as the amygdala and nucleus accumbens are especially important for sexual motivation (see Figure 11.19). Damage to these areas results in a decreased motivation to engage in sexual behaviour, while leaving the ability to do so intact (Everett, 1990). Similar dissociations of sexual motivation and sexual ability have also been observed in the female rat (Becker, Rudick, & Jenkins, 2001; Jenkins & Becker, 2001).

The sexual response cycle and sexual desire are regulated by the sex hormones estrogen in women and testosterone in both women and in men. Although the hormones are secreted by the ovaries and testes, it is the hypothalamus and the pituitary glands that control the process. Estrogen levels in women vary across the menstrual cycle, peaking during ovulation (Pillsworth, Haselton, & Buss, 2004). Women are more interested in having sex during ovulation but can experience high levels of sexual arousal throughout the menstrual cycle.

In men, testosterone is essential to maintain sexual desire and to sustain an erection, and testosterone injections can increase sexual interest and performance (Aversa et al., 2000; Jockenhövel et al., 2009). Testosterone is also important in the female sex cycle. Women who are experiencing menopause may develop a loss of interest in sex, but this interest may be rekindled through estrogen and testosterone replacement treatments (Meston & Frohlich, 2000).

Although their biological determinants and experiences of sex are similar, men and women differ substantially in their overall interest in sex, the frequency of their sexual activities, and the mates they are most interested in. Men show a more consistent interest in sex, whereas the sexual desires of women are more likely to vary over time (Baumeister, 2000). Men fantasize about sex more often than women, and their fantasies are more physical and less intimate (Leitenberg & Henning, 1995). Men are also more willing to have casual sex than are women, and their standards for sex partners is lower (Petersen & Hyde, 2010; Saad, Eba, & Sejean, 2009).

Gender differences in sexual interest probably occur in part as a result of the evolutionary predispositions of men and women, and this interpretation is bolstered by the finding that gender differences in sexual interest are observed cross-culturally (Buss, 1989). Evolutionarily, women should be more selective than men in their choices of sex partners because they must invest more time in bearing and nurturing their children than men do. Most men do help out, of course, but women simply do more (Buss & Kenrick, 1998). Because they do not need to invest a lot of time in child rearing, men may be evolutionarily predisposed to be more willing and desiring of having sex with many different partners and may be less selective in their choice of mates. Women, on the other hand, because they must invest substantial effort in raising each child, should be more selective.

Kinsey’s research

Before the late 1940s, access to reliable, empirically-based information on sex was limited. Physicians were considered authorities on all issues related to sex, despite the fact that they had little to no training in these issues, and it is likely that most of what people knew about sex had been learned either through their own experiences or by talking with their peers. Convinced that people would benefit from a more open dialogue on issues related to human sexuality, Dr. Alfred Kinsey of Indiana University initiated large-scale survey research on the topic (see Figure 11.20). The results of some of these efforts were published in two books — Sexual Behavior in the Human Male and Sexual Behavior in the Human Female — which were published in 1948 and 1953, respectively (Bullough, 1998).

Although Kinsey’s research has been widely criticized as being riddled with sampling and statistical errors (Jenkins, 2010), there is little doubt that this research was very influential in shaping future research on human sexual behaviour and motivation. Kinsey described a remarkably diverse range of sexual behaviours and experiences reported by the volunteers participating in his research. Behaviours that had once been considered exceedingly rare or problematic were demonstrated to be much more common and innocuous than previously imagined (Bancroft, 2004; Bullough, 1998).

The following YouTube link is the trailer from the 2004 film Kinsey that depicts Alfred Kinsey’s life and research:

- Video: Kinsey (2004) – Movie Trailer (ciwciwdotcom, 2009)

Among the results of Kinsey’s research were the findings that women are as interested and experienced in sex as their male counterparts, that both males and females masturbate without adverse health consequences, and that homosexual acts are fairly common (Bancroft, 2004). Kinsey also developed a continuum known as the Kinsey scale that is still commonly used today to categorize an individual’s sexual orientation (Jenkins, 2010). Sexual orientation is an individual’s emotional and erotic attractions to same-sexed individuals (i.e., homosexual), opposite-sexed individuals (i.e., heterosexual), or both (i.e., bisexual).

Masters and Johnson’s research

In 1966, William Masters and Virginia Johnson published a book detailing the results of their observations of nearly 700 people who agreed to participate in their study of physiological responses during sexual behaviour. Unlike Kinsey, who used personal interviews and surveys to collect data, Masters and Johnson (1966) observed people having intercourse in a variety of positions, and they observed people masturbating, manually or with the aid of a device. While this was occurring, researchers recorded measurements of physiological variables, such as blood pressure and respiration rate, as well as measurements of sexual arousal, such as vaginal lubrication and penile tumescence, which is the swelling associated with an erection. In total, Masters and Johnson observed nearly 10,000 sexual acts as a part of their research (Hock, 2008).

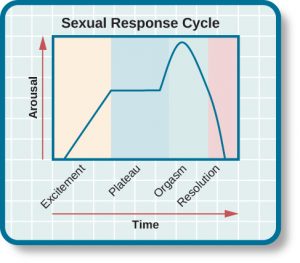

Based on these observations, Masters and Johnson (1966) divided the sexual response cycle into four phases that are fairly similar in men and women: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution (see Figure 11.21). The excitement phase is the arousal phase of the sexual response cycle, and it is marked by erection of the penis or clitoris and lubrication and expansion of the vaginal canal. During plateau, women experience further swelling of the vagina and increased blood flow to the labia minora, and men experience full erection and often exhibit pre-ejaculatory fluid. Both men and women experience increases in muscle tone during this time. Orgasm is marked in women by rhythmic contractions of the pelvis and uterus along with increased muscle tension. In men, pelvic contractions are accompanied by a buildup of seminal fluid near the urethra that is ultimately forced out by contractions of genital muscles (i.e., ejaculation). Resolution is the relatively rapid return to an unaroused state accompanied by a decrease in blood pressure and muscular relaxation. While many women can quickly repeat the sexual response cycle, men must pass through a longer refractory period as part of resolution. The refractory period is a period of time that follows an orgasm during which an individual is incapable of experiencing another orgasm. In men, the duration of the refractory period can vary dramatically from individual to individual with some refractory periods as short as several minutes and others as long as a day. As men age, their refractory periods tend to span longer periods of time.

In addition to the insights that their research provided with regards to the sexual response cycle and the multi-orgasmic potential of women, Masters and Johnson also collected important information about reproductive anatomy. Their research demonstrated the oft-cited statistic of the average size of a flaccid and an erect penis — 7.6 cm and 15.2 cm, respectively — as well as dispelling long-held beliefs about relationships between the size of a man’s erect penis and his ability to provide sexual pleasure to his female partner. Furthermore, they determined that the vagina is a very elastic structure that can conform to penises of various sizes (Hock, 2008).

Source: Adapted from Bhatia and Loewenstein (2020) and Spielman et al. (2019).

Key Takeaways

- Biologically, hunger is controlled by the interactions among complex pathways in the nervous system and a variety of hormonal and chemical systems in the brain and body.

- How we eat is also influenced by our environment, including social norms about appropriate body size.

- Homeostasis varies among people and is determined by the basal metabolic rate. Low metabolic rates, which are determined entirely by genetics, make weight management a very difficult undertaking for many people.

- Eating disorders, including anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, affect about 1% of people, of which 90% are women.

- Obesity is a medical condition in which so much excess body fat has accumulated in the body that it begins to have an adverse impact on health. Uncontrolled obesity leads to health problems including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, sleep apnea, arthritis, and some types of cancer.

- The two approaches to controlling weight are to eat less and exercise more.

- Sex drive is regulated by the sex hormones estrogen in women and testosterone in both women and men.

- Although their biological determinants and experiences of sex are similar, men and women differ substantially in their overall interest in sex, the frequency of their sexual activities, and the mates they are most interested in.

- Sexual behaviour varies widely, not only between men and women, but also within each sex.

- There is also variety in sexual orientation: toward people of the opposite sex, people of the same sex, or people of both sexes. The determinants of sexual orientation are primarily biological.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Consider your own eating and sex patterns. Are they healthy or unhealthy? What can you do to improve them?

- Given that BMI is calculated solely on weight and height, how could it be misleading?

- Caucasian women from industrialized, Western cultures tend to be at the highest risk for eating disorders like anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Why might this be?

- While much research has been conducted on how an individual develops a given sexual orientation, many people question the validity of this research, citing that the participants used may not be representative. Why do you think this might be a legitimate concern?

Congratulations on completing Chapter 11! Remember to go back to the section on Approach and Pedagogy near the beginning of the book to learn more about how to get the most out of reading and learning the material in this textbook.

Image Attributions

Figure 11.14. Buffet Open All You Can Eat by Jeremy Brooks is used under a CC BY-NC 2.0 license.

Figure 11.15. Food at Wiki Indaba by Icem4k is used under the CC BY-SA 4.0 International license.

Figure 11.16. Toni Maticevski: New York Fashion Week Fall 2007 by Peter Duhon is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 11.17. After Love Making by Matthew Romack is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 11.18. WT and TK Rat Photo by Jason Snyder is used under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Figure 11.19. Used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Figure 11.20. Used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Figure 11.21. Used under a CC BY 4.0 license.

References

American Heart Association. (1998). Statement on exercise, benefits and recommendations for physical activity programs for all Americans. American Heart Association, 94, 857–862.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Feeding and eating disorders. Retrieved from http://www.dsm5.org/documents/eating%20disorders%20fact%20sheet.pdf

Anand, B. K., & Brobeck, J. R. (1951). Hypothalamic control of food intake in rats and cats. The Yale journal of biology and medicine, 24(2), 123.

Andersson, B. (1951). The effect and localization of electrical stimulation of certain parts of the brain stem in sheep and goats. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 23(1), 8–23.

Ariely, D., & Loewenstein, G. (2006). The heat of the moment: The effect of sexual arousal on sexual decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 19(2), 87–98.

Aversa, A., Isidori, A., De Martino, M., Caprio, M., Fabbrini, E., Rocchietti-March, M.,…Fabri, A. (2000). Androgens and penile erection: evidence for a direct relationship between free testosterone and cavernous vasodilation in men with erectile dysfunction. Clinical Endocrinology, 53(4), 517–522.

Bancroft, J. (2004). Alfred C. Kinsey and the politics of sex research. Annual Review of Sex Research, 15, 1–39.

Baumeister, R. F. (2000). Gender differences in erotic plasticity: The female sex drive as socially flexible and responsive. Psychological Bulletin, 126(3), 347–374.

Becker, J. B., Rudick, C. N., & Jenkins, W. J. (2001). The role of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and striatum during sexual behavior in the female rat. Journal of Neuroscience, 21, 3236–3241.

Bhasin, S., Enzlin, P., Coviello, A., & Basson, R. (2007). Sexual dysfunction in men and women with endocrine disorders. The Lancet, 369, 597–611.

Bhatia, S. & Loewenstein, G. (2020). Drive states. In R. Biswas-Diener & E. Diener (Eds.), Noba textbook series: Psychology. Champaign, IL: DEF. Retrieved from http://noba.to/pjwkbt5h

Biderman, A. D. (1960). Social-psychological needs and “involuntary” behavior as illustrated by compliance in interrogation. Sociometry, 23(2), 120–147.

Borer, K. T. (2008). How effective is exercise in producing fat loss? Kinesiology, 40(2), 126–137.

Brendl, C. M., Markman, A. B., & Messner, C. (2003). The devaluation effect: Activating a need devalues unrelated objects. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(4), 463–473.

Bullough, V. L. (1998). Alfred Kinsey and the Kinsey report: Historical overview and lasting contributions. The Journal of Sex Research, 35, 127–131.

Buss, D. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12(1), 1–49.

Buss, D., & Kenrick, D. (1998). Evolutionary social psychology. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of Social Psychology (4th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 982–1026). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Canadian Mental Health Association. (n.d.). Eating disorders. Retrieved from https://cmha.ca/mental-health/understanding-mental-illness/eating-disorders

Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. (2019). Canadian 24-hour movement guidelines: An integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Retrieved from https://csepguidelines.ca

Carter, C. S. (1992). Hormonal influences on human sexual behavior. In J. B. Becker, S. M. Breedlove, & D. Crews (Eds.), Behavioral Endocrinology (pp.131–142). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

ciwciwdotcom. (2009, October 28). Kinsey (2004) – Movie trailer [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e19GnyNdC48

Collier, D. A., & Treasure, J. L. (2004). The aetiology of eating disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 185, 363–365.

Colley, R. C., Garriguet, D., Janssen, I., Craig, C. L., Clarke, J., & Tremblay, M. S. (2011). Physical activity of Canadian adults: Accelerometer results from the 2007 to 2009 Canadian Health Measures Survey. Health Reports, 22(1), 1–8.

Conrad, P. (2005). The shifting engines of medicalization. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46, 3–14.

Crandall, C. S., Merman, A., & Hebl, M. (2009). Anti-fat prejudice. In T. D. Nelson (Ed.), Handbook of prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination (pp. 469–487). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Douketis, J. D., Macie C., Thabane, L., & Williamson, D. F. (2005). Systematic review of long-term weight loss studies in obese adults: Clinical significance and applicability to clinical practice. International Journal of Obesity, 29, 1153–1167.

Easterbrook, J. A. (1959). The effect of emotion on cue utilization and the organization of behavior. Psychological Review, 66(3).

Everett, B. J. (1990). Sexual motivation: A neural and behavioural analysis of the mechanisms underlying appetitive and copulatory responses of male rats. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 14, 217–232.

Gawin, F. H. (1991). Cocaine addiction: psychology and neurophysiology. Science, 251(5001), 1580–1586.

Giordano, L. A., Bickel, W. K., Loewenstein, G., Jacobs, E. A., Marsch, L., & Badger, G. J. (2002). Mild opioid deprivation increases the degree that opioid-dependent outpatients discount delayed heroin and money. Psychopharmacology, 163(2), 174–182.

Greenberg, D., Smith, G. P., & Gibbs, J. (1990). Intraduodenal infusions of fats elicit satiety in sham-feeding rats. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative, and Comparative Physiology, 259(1), 110–118.

Gustafson, D., Rothenberg, E., Blennow, K., Steen, B., & Skoog, I. (2003). An 18-year follow-up of overweight and risk of Alzheimer disease. Archives of Internal Medicine, 163(13), 1524.

Haslam, D. W., & James, W. P. (2005). Obesity. Lancet, 366(9492), 197–209.

Hock, R. R. (2008). Emotion and Motivation. In Forty studies that changed psychology: Explorations into the history of psychological research (6th ed.) (pp. 158–168). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

James, W. P. (2008). The fundamental drivers of the obesity epidemic. Obesity Review, 9(Suppl. 1), 6–13.

Jenkins, W. J. (2010). Can anyone tell me why I’m gay? What research suggests regarding the origins of sexual orientation. North American Journal of Psychology, 12, 279–296.

Jenkins, W. J., & Becker, J. B. (2001). Role of the striatum and nucleus accumbens in paced copulatory behavior in the female rat. Behavioural Brain Research, 121, 19–28.

Jockenhövel, F., Minnemann, T., Schubert, M., Freude, S., Hübler, D., Schumann, C.,…Ernst, M. (2009). Timetable of effects of testosterone administration to hypogonadal men on variables of sex and mood. Aging Male, 12(4), 113–118.

Kinsey, A. C. (1998). Sexual behavior in the human female. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. (Original work published 1953)

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1998). Sexual behavior in the human male. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. (Original work published 1948)

Kirchhoff, A., Elliott, L., Schlichting, J., & Chin, M. (2008). Strategies for physical activity maintenance in African American women. American Journal of Health Behavior, 32(5), 517–524.

Kramer, A. F., Erickson, K. I., & Colcombe, S. J. (2006). Exercise, cognition, and the aging brain. Journal of Applied Physiology, 101(4), 1237–1242.

Leitenberg, H., & Henning, K. (1995). Sexual fantasy. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 469–496.

Masters, W. H., & Johnson, V. E. (1966). Human sexual response. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

Mayo Clinic. (2012a). Anorexia nervosa. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/anorexia/DS00606

Mayo Clinic. (2012b). Bulimia nervosa. Retrieved from http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/bulimia/DS00607

Meston, C. M., & Frohlich, P. F. (2000). The neurobiology of sexual function. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(11), 1012–1030.

Miller, W. C. (1999). How effective are traditional dietary and exercise interventions for weight loss? Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 31(8), 1129–1134.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (n.d.). Calculate your body mass index. Retreived from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/lose_wt/BMI/bmicalc.htm

Nestle, M., & Jacobson, M. F. (2000). Halting the obesity epidemic: A public health policy approach. Public Health Reports, 115(1), 12–24.

Norton, K. I., Olds, T. S., Olive, S., & Dank, S. (1996). Ken and Barbie at life size. Sex Roles, 34(3–4), 287–294.

Petersen, J. L., & Hyde, J. S. (2010). A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993–2007. Psychological Bulletin, 136(1), 21–38.

Pillsworth, E., Haselton, M., & Buss, D. (2004). Ovulatory shifts in female sexual desire. Journal of Sex Research, 41(1), 55–65.

Rolls, E. T. (2000). The orbitofrontal cortex and reward. Cerebral Cortex, 10(3), 284-294.

Rozin, P., Dow, S., Moscovitch, M., & Rajaram, S. (1998). What causes humans to begin and end a meal? A role for memory for what has been eaten, as evidenced by a study of multiple meal eating in amnesic patients. Psychological Science, 9(5), 392–396.

Saad, G., Eba, A., & Sejean, R. (2009). Sex differences when searching for a mate: A process-tracing approach. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 22(2), 171–190.

Schachter, S. (1968). Obesity and eating. Science, 161(3843), 751–756.

Schomer, H., & Drake, B. (2001). Physical activity and mental health. International SportMed Journal, 2(3), 1.

Sherwin, B. B. (1988). A comparative analysis of the role of androgen in human male and female sexual behavior: Behavioral specificity, critical thresholds, and sensitivity. Psychobiology, 16, 416–425.

Smink, F. R. E., van Hoeken, D., & Hoek, H. W. (2012). Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence, and mortality rates. Current Psychiatry Reports, 14, 406–414.

Spielman, R., Dumper, K., Jenkins, W., Lacombe, A., Lovett, M., & Perlmutter, M. (2019). Emotions and motivation. In OpenStax, Psychology. OpenStax CNX. Retrieved from https://cnx.org/contents/Sr8Ev5Og@10.16:UQgvP5NH@9

Statistics Canada. (2017). Physical activity of Canadian children and youth. Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310037301

Statistics Canada. (2019a). Overweight and obesity based on measured body mass index, by age group and sex (Table 13-10-0373-01). Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310037301

Statistics Canada. (2019b). Physical activity, self reported, adult, by age group (Table 13-10-0096-13). Retrieved from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310009613

Teitelbaum, P. (1955). Sensory control of hypothalamic hyperphagia. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology, 48(3), 156.

Walker, P. (2014). Castaway’s sea savvy could have helped him survive year adrift, says expert. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/feb/04/castaway-jose-salvador-alvarenga-survival-expert

Zajonc, R. B. (1998). Emotions. In Gilbert, D. T., Fiske, S. T., & Lindzey, G. (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (Vols. 1 and 2, 4th ed., pp. 591–632). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.