6.4 Using the Principles of Learning in Everyday Life

Learning Objectives

- Describe how classical conditioning is used by advertisers to sell products.

- Describe how operant conditioning can be used for behaviour modification.

- Describe how punishment can be effective.

- Describe how the use of rewards can be problematic.

The principles of learning are some of the most general and most powerful in all of psychology. It would be fair to say that these principles account for more behaviour using fewer principles than any other set of psychological theories. The principles of learning are applied in numerous ways in everyday settings. For example, operant conditioning has been used to motivate employees, to improve athletic performance, to increase the functioning of those suffering from developmental disabilities, and to help parents successfully toilet train their children (Azrin & Foxx, 1974; McGlynn, 1990; Pedalino & Gamboa, 1974; Simek & O’Brien, 1981). In this section, we will consider how learning theories are used in real life.

Using classical conditioning in advertising

Classical conditioning has long been, and continues to be, an effective tool in marketing and advertising (Hawkins, Best, & Coney, 1998). The general idea is to create an advertisement that has positive features such that the ad creates enjoyment in the person exposed to it. The enjoyable ad serves as the unconditioned stimulus (US), and the enjoyment is the unconditioned response (UR). Because the product being advertised is mentioned in the ad, it becomes associated with the US, and it then becomes the conditioned stimulus (CS). In the end, if everything has gone well, seeing the product online or in the store will then create a positive response in the buyer, leading them to be more likely to purchase the product.

A similar strategy is used by corporations that sponsor teams or events. For instance, if people enjoy watching a university basketball team playing basketball and if that team is sponsored by a product, such as Pepsi, then people may end up experiencing positive feelings when they view a can of Pepsi. Of course, the sponsor wants to sponsor only good teams and good athletes because these create more pleasurable responses.

Advertisers use a variety of techniques to create positive advertisements, including enjoyable music, cute babies, attractive models, and funny spokespeople. In one study, Gerald Gorn (1982) showed research participants pictures of different writing pens of different colours but paired one of the pens with pleasant music and the other with unpleasant music. When given a choice as a free gift, more people chose the pen colour associated with the pleasant music. Christian Schemer, Jörg Matthes, Werner Wirth, and Samuel Textor (2008) found that people were more interested in products that had been embedded in music videos of artists that they liked and less likely to be interested when the products were in videos featuring artists that they did not like.

Another type of ad that is based on principles of classical conditioning is one that associates fear with the use of a product or behaviour, such as those that show pictures of deadly automobile accidents to encourage seatbelt use or images of lung cancer surgery to discourage smoking. These ads have also been found to be effective (Das, de Wit, & Stroebe, 2003; Perloff, 2003; Witte & Allen, 2000), due in large part to conditioning. When we see a cigarette and the fear of dying has been associated with it, we are hopefully less likely to light up.

There is ample evidence of the utility of classical conditioning, using both positive as well as negative stimuli, in advertising. This does not, however, mean that we are always influenced by these ads. The likelihood of conditioning being successful is greater for products that we do not know much about, where the differences between products are relatively minor and when we do not think too carefully about the choices (Schemer et al., 2008).

Using operant conditioning in behaviour modification

The components of operant conditioning can be put together to systematically change behaviour in real life: this is called behaviour modification. Behaviour modification has myriad practical applications, such as overcoming insomnia, toilet training for toddlers, communication skills for people with autism, social skills training, time management and study skills training for students, eliminating bad habits, and so on. Behaviour modification is based on the assumption that behaviours can be added, eliminated, or modified by changing the environment that produces behaviours as well as the consequences of behaviour. Identifying when and where behaviours do or do not occur, as well as the reinforcements and punishments that maintain behaviours, are key components to behaviour modification. Before attempting to change behaviour, it is necessary to observe and identify what behaviour is occurring, as well as when, where, how often, and so on. The maintainers of behaviour are assumed to be in the environment. Once the antecendets and maintainers of behaviour are changed, the behaviour itself will change.

Using punishment

The use of punishment to change or shape behaviour is controversial. Many people feel strongly against the use of corporal punishment (i.e., punishment involving physical discipline such as slapping or spanking). Equally, there are people who were corporally punished as a child and feel it did them no lasting harm. The Criminal Code of Canada does permit the use of some corporal punishment by parents of children under 18 with certain limits (Justice for Children and Youth, 2013). Teachers are no longer allowed to physically punish children; as late as the 1970’s teachers in Canada were allowed to administer “the strap” as punishment to students (Axelrod, 2011). The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (2019) argues that physical discipline violates children’s’ rights and should be legally prohibited.

As psychologists, we are very interested in what the evidence says about the use of corporal punishment. One important thing to keep in mind is that this is a topic that cannot be studied experimentally; it would be ethically impossible to have parents spank their children to see what the effects might be. Thus, understanding cause and effect from correlational research is extremely challenging. As well, it is a given that parents will need to teach their children using discipline — a term that can be interpreted in a variety of ways. The complexities inherent in studying the use of corporal punishment have resulted in divergent findings (e.g., Gershoff, 2002). Physical discipline in children is associated with negative child outcomes including aggression, antisocial behaviour, and mental health problems. Most professionals advise parents against the use of physical punishment.

Psychology in Everyday Life

Operant conditioning in the classroom

John Watson and B. F. Skinner believed that all learning was the result of reinforcement and that reinforcement could be used to educate children. For instance, Watson wrote in his book on behaviourism:

Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I’ll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select — doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief and, yes, even beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations, and race of his ancestors. I am going beyond my facts and I admit it, but so have the advocates of the contrary and they have been doing it for many thousands of years. (Watson, 1930, p. 82)

Skinner promoted the use of programmed instruction, an educational tool that consists of self-teaching with the aid of a specialized textbook or teaching machine that presents material in a logical sequence (Skinner, 1965). Programmed instruction allows students to progress through a unit of study at their own rate, checking their own answers and advancing only after answering correctly. Programmed instruction is used today in many classes — for instance, to teach computer programming (Emurian, 2009).

Although reinforcement can be effective in education and teachers make use of it by awarding gold stars, good grades, and praise, there are also substantial limitations to using reward to improve learning. To be most effective, rewards must be contingent on appropriate behaviour. In some cases, teachers may distribute rewards indiscriminately — for instance, by giving praise or good grades to children whose work does not warrant it — in the hope that students will feel good about themselves and that this self-esteem will lead to better performance. Studies indicate, however, that high self-esteem alone does not improve academic performance (Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, 2003). When rewards are not earned, they become meaningless and no longer provide motivation for improvement.

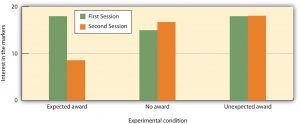

Another potential limitation of rewards is that they may teach children that the activity should be performed for the reward rather than for one’s own interest in the task. If rewards are offered too often, the task itself becomes less appealing. Mark Lepper, David Green, and Richard Nisbett (1973) studied this possibility by leading some children to think that they engaged in an activity for a reward, rather than because they simply enjoyed it. First, they placed some fun felt-tipped markers in the classroom of the children they were studying. The children loved the markers and played with them right away. Then, the markers were taken out of the classroom, and the children were given a chance to play with the markers individually at an experimental session with the researcher. At the research session, the children were randomly assigned to one of three experimental groups. One group of children — the “expected reward” condition — was told that if they played with the markers they would receive a good drawing award. A second group — the “unexpected reward” condition — also played with the markers and also got an award, but they were not told ahead of time that they would be receiving an award; instead, it came as a surprise after the session. The third group — the “no reward” group — played with the markers too, but they did not receive an award.

Then, the researchers placed the markers back in the classroom and observed how much the children in each of the three groups played with them. The children who had been led to expect a reward for playing with the markers during the experimental session played with the markers less at the second session than they had at the first session (see Figure 6.9). The idea is that, when the children had to choose whether or not to play with the markers when the markers reappeared in the classroom, they based their decision on their own prior behaviour. The children in the no reward group and the children in the unexpected reward group realized that they played with the markers because they liked them. Children in the expected award condition, however, remembered that they were promised a reward for the activity the last time they played with the markers. These children, then, were more likely to draw the inference that they play with the markers only for the external reward, and because they did not expect to get an award for playing with the markers in the classroom, they determined that they didn’t like them. Expecting to receive the award at the session had undermined their initial interest in the markers.

This research suggests that, although receiving a reward may in many cases lead us to perform an activity more frequently or with more effort, a reward may not always increase our liking for the activity. In some cases, a reward may actually make us like an activity less than we did before we were rewarded for it. This outcome is particularly likely when the reward is perceived as an obvious attempt on the part of others to get us to do something. When children are given money by their parents to get good grades in school, they may improve their school performance to gain the reward, but at the same time their liking for school may decrease. On the other hand, rewards that are seen as more internal to the activity, such as rewards that praise us, remind us of our achievements in the domain, and make us feel good about ourselves as a result of our accomplishments, are more likely to be effective in increasing not only the performance of, but also the liking of, the activity (Hulleman, Durik, Schweigert, & Harackiewicz, 2008; Ryan & Deci, 2002).

Other research findings also support the general principle that punishment is generally less effective than reinforcement in changing behaviour. In a recent meta-analysis, Elizabeth Gershoff (2002) found that although children who were spanked by their parents were more likely to immediately comply with the parents’ demands, they were also more aggressive, showed less ability to control aggression, and had poorer mental health in the long term than children who were not spanked. The problem seems to be that children who are punished for bad behaviour are likely to change their behaviour only to avoid the punishment rather than by internalizing the norms of being good for its own sake. Punishment also tends to generate anger, defiance, and a desire for revenge. Moreover, punishment models the use of aggression and ruptures the important relationship between the teacher and the learner (Kohn, 1993).

Key Takeaways

- Learning theories have been used to change behaviours in many areas of everyday life.

- Some advertising uses classical conditioning to associate a pleasant response with a product.

- Rewards are frequently and effectively used in education but must be carefully designed to be contingent on performance and to avoid undermining interest in the activity.

Exercises and Critical Thinking

- Find some examples of advertisements that make use of classical conditioning to create positive attitudes toward products.

- Should parents use both punishment as well as reinforcement to discipline their children? On what principles of learning do you base your opinion?

Congratulations on completing Chapter 6! Remember to go back to the section on Approach and Pedagogy near the beginning of the book to learn more about how to get the most out of reading and learning the material in this textbook.

Image Attributions

Figure 6.9. Used under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Long Descriptions

Figure 6.9. Undermining intrinsic interest:

| First Session | Second Session | |

|---|---|---|

| Expected award | 17 | 8 |

| No award | 15 | 16 |

| Unexpected award | 17 | 17 |

References

Axelrod, P. (2011). Banning the strap: The end of corporal punishment in Canadian schools. EdCan Network. Retrieved from https://www.edcan.ca/articles/banning-the-strap-the-end-of-corporal-punishment-in-canadian-schools

Azrin, N., & Foxx, R. M. (1974). Toilet training in less than a day. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4, 1–44.

Das, E., de Wit, J., & Stroebe, W. (2003). Fear appeals motivate acceptance of action recommendations: Evidence for a positive bias in the processing of persuasive messages. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(5), 650–664.

Emurian, H. H. (2009). Teaching Java: Managing instructional tactics to optimize student learning. International Journal of Information & Communication Technology Education, 3(4), 34–49.

Gershoff, E. T. (2002). Corporal punishment by parents and associated child behaviors and experiences: A meta-analytic and theoretical review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 539–579.

Gorn, G. J. (1982). The effects of music in advertising on choice behavior: A classical conditioning approach. Journal of Marketing, 46(1), 94–101.

Hawkins, D., Best, R., & Coney, K. (1998). Consumer behavior: Building marketing strategy (7th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Hulleman, C. S., Durik, A. M., Schweigert, S. B., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2008). Task values, achievement goals, and interest: An integrative analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 398–416.

Justice for Children and Youth. (2013). Corporal punishment and “spanking.” Retrieved from http://jfcy.org/en/rights/corporal-punishment-aka-spanking

Kohn, A. (1993). Punished by rewards: The trouble with gold stars, incentive plans, A’s, praise, and other bribes. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Lepper, M. R., Greene, D., & Nisbett, R. E. (1973). Undermining children’s intrinsic interest with extrinsic reward: A test of the “overjustification” hypothesis. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 28(1), 129–137.

McGlynn, S. M. (1990). Behavioral approaches to neuropsychological rehabilitation. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 420–441.

Pedalino, E., & Gamboa, V. U. (1974). Behavior modification and absenteeism: Intervention in one industrial setting. Journal of Applied Psychology, 59, 694–697.

Perloff, R. M. (2003). The dynamics of persuasion: Communication and attitudes in the 21st century (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic-dialectical perspective. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 3–33). Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

Schemer, C., Matthes, J. R., Wirth, W., & Textor, S. (2008). Does “Passing the Courvoisier” always pay off? Positive and negative evaluative conditioning effects of brand placements in music videos. Psychology & Marketing, 25(10), 923–943.

Simek, T. C., & O’Brien, R. M. (1981). Total golf: A behavioral approach to lowering your score and getting more out of your game. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Skinner, B. F. (1965). The technology of teaching. Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences, 162(989): 427–43.

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights. (2019). Ending corporal punishment of children. Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/CorporalPunishment.aspx

Watson, J. B. (1930). Behaviorism (Rev. ed.). New York, NY: Norton.

Witte, K., & Allen, M. (2000). A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education & Behavior, 27(5), 591–615.